With a swooping P, a curling H, a slanted I and a looped L, Gov. Philip D. Murphy of New Jersey — on his last full day in office on Monday — signed into law a bill requiring that all third, fourth and fifth graders in the state learn cursive.

Though script is little used these days beyond checkbooks and autographs, New Jersey joins roughly two dozen other states that have inscribed similar rules in recent years, bucking a drop-off in cursive instruction that began in 2010, when the federal government removed it from the Common Core Standards for students in kindergarten through 12th grade.

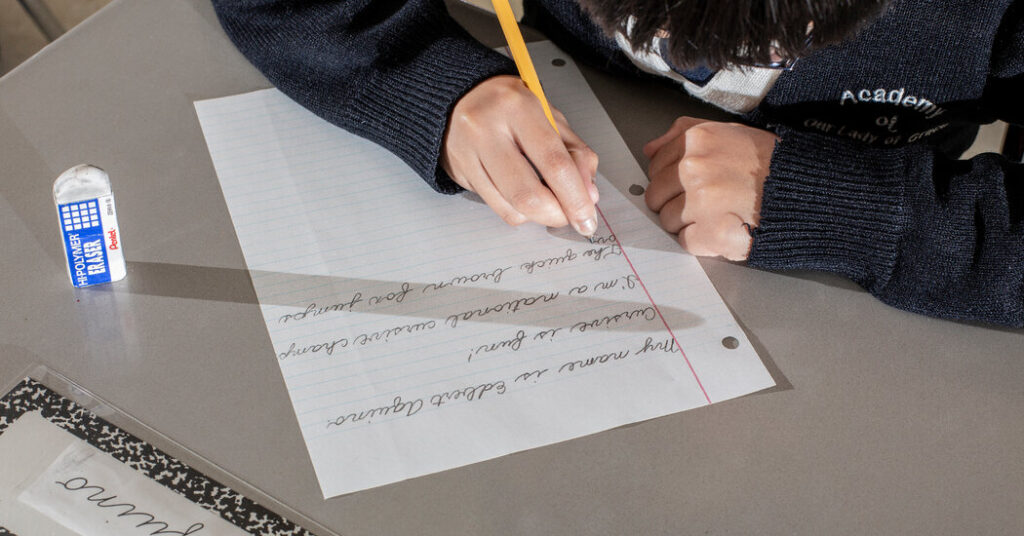

Proponents of cursive cite studies that link handwriting to better information retention and writing speed, and say — as Mr. Murphy did in a statement released as he signed the bill — that knowing script can help people read the original U.S. Constitution.

Learning cursive will provide New Jersey students with “the skills they need to read our nation’s founding documents,” as well as write checks and improve cognition, Mr. Murphy said on Monday, a day before relinquishing his office to the state’s new Democratic governor, Mikie Sherrill.

The requirement takes effect immediately and applies to the next full school year, according to Kevin Dehmer, the state’s education commissioner. “Ensuring that all students learn cursive handwriting reinforces not just a traditional skill, but developmental foundations that support fine motor development, literacy skills and student confidence,” Mr. Dehmer said in a statement.

On Tuesday, Gabrielle and Kurt McCann, of Lebanon, N.J., were waiting to break the news to their 9-year-old son, Atlas McCann, when he got home from school. “I think it is important that kids are able to use that refined motor skill,” Ms. McCann said in an interview shortly after a meeting where she said she had taken all her notes in longhand.

But Atlas, she said, was thinking, “What’s the point of having to sit here and torture myself?”

“Hopefully in the long run, he will see it has value,” Ms. McCann said.

Some experts share Atlas’s viewpoint. “Oh, God,” Morgan Polikoff, an education professor at the University of Southern California, said when he learned of the New Jersey law. Mr. Polikoff acknowledged the studies showing the benefits of handwriting, but he pointed out that most were not specific to script.

He attributed the renewed affection for the style’s curlicues and squiggles to “boomerish nostalgia,” and said he was struck by cursive’s bipartisan appeal, with states as different politically as Arkansas and California requiring its instruction. Conservatives, the professor said, promote its utility for reading old documents; liberals like it for its beauty as an art form.

“It is a very strange phenomenon, but the fact that you have states left, right and center adopting mandates that children learn cursive is not something I could have predicted,” Mr. Polikoff added. “Who hand-writes hardly anything?”

Renewed passion for cursive often coincides with moments of societal tumult, said Tamara Plakins Thornton, a history professor emerita at the State University of New York at Buffalo and the author of “Handwriting in America: A Cultural History.” The feminist revolution of the 1960s, for example, led to a comeback for script, she said.

“It has long been obsolete; it’s been obsolete since the typewriter came around,” Ms. Platkins Thorton said. “The fact that it is obsolete makes it all the more appealing: ‘Let’s go run back to that past.’”

At least one New Jersey child is eager to embrace cursive instruction: A year ago, Eleanor Covucci, a kindergartner at a charter school in Jersey City, was the state’s Northeast regional winner in the National Handwriting Competition sponsored by Zaner-Bloser, a company that publishes cursive workbooks.

For her winning entry, Eleanor, then 5 years old, wrote “I like how there are many ways to make words” — in print as opposed to script, as was required for competitors in her age group. She still proudly wears the medal everywhere, including at the airport, her mother, Amber Covucci, said, and is already gearing up for cursive competitions, which will be more difficult.

Eleanor, now 6, said she was ready for the challenge. She can already write her name in cursive, she said, and even her nickname, Ellie — almost.

“I am actually pretty good at that word,” she said. “I am sort of kind of good at cursive.”

Sarah Maslin Nir is a Times reporter covering anything and everything New York … and sometimes beyond.

The post Cursive Makes a Comeback in New Jersey Schools appeared first on New York Times.