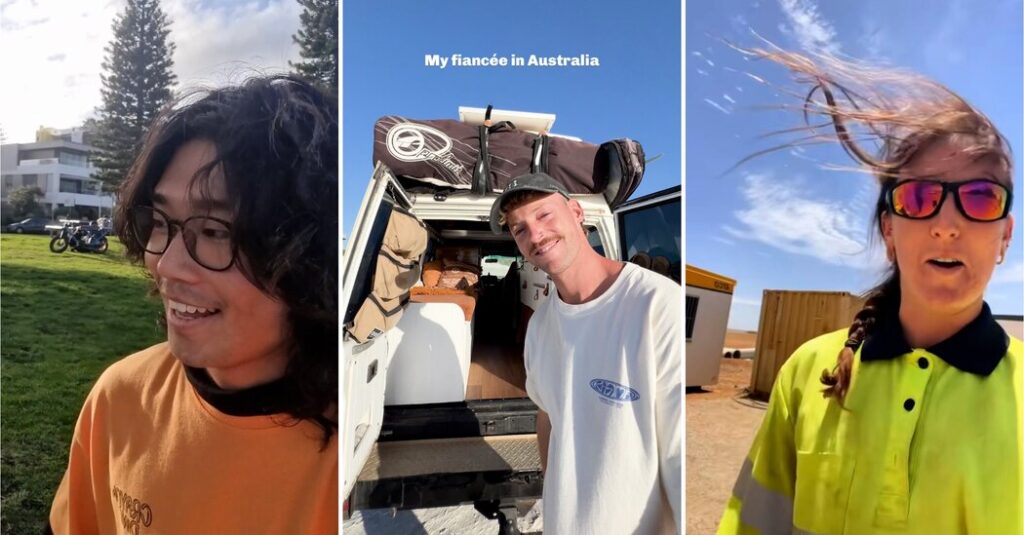

A couple of years into traveling around Australia, Abigail Phillips noticed something about her fiancé, Alex Meston: He was looking good. Real good.

Whereas he used to be pale and formally dressed back home in Brighton, England, he was now golden, barefoot, shirtless and beaming, with a ’tache — British shorthand for mustache — and crop of curls escaping the back of his hat. Something, she thought, had bloomed for Mr. Meston, 32. Forget TikTok’s “girlfriend effect” — this glow-up was what Miss Phillips, 29, considered the “Australia effect.”

In July, she posted an Instagram reel of the transformation, listing key identifiers: he shops at the home-improvement store Bunnings twice a day; loves a “snag,” or sausage; has a “baby mullet”; “grew more freckles.” Similar videos — and mullets — were soon seen across social media.

Both Miss Phillips and Mr. Meston were supporting themselves with temporary jobs as a physical therapists around the country. The “working holiday” in Australia has been a draw for a certain segment of young foreigners dating back to 1975, when Parliament established the Working Holiday Maker Program as a mechanism for cultural exchange. Now citizens from 44 countries in Europe, Asia, South America and North America (including the United States) are eligible for visas that allow them to stay as long as three years.

Applicants must be between ages 18 and 30 (or 35 for a few countries, including Britain) and willing to work in areas where there is a need, like agriculture, health care and bush fire recovery, to name a few. They must also have two years of higher education; speak “functional” English; meet health and background requirements; and, though the work is paid, arrive with enough money to support themselves. (The government recommends about $3,000.)

Of course, those living out their coming-of-age stories against the backdrop of mangroves, lighthouses and pineapple farms have a narrow window into the country. Australia is home to the some of the oldest living cultures, and, like so many other countries, struggles with far less rosy issues like climate change, anti-immigrant nationalism and terrorism, like the mass shooting during a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach in December.

But travelers do get exposed to a certain cultural gist, and that includes sun, beach, bush … and more sun. By late 2025, more travelers were posting videos to social media of desk jobs traded for physical labor and morning runs under gum trees, set to Don MacLean’s “American Pie” and its chorus of “bye-bye.”

In December 2023, Vincenzo De Leo of Weiden, Germany, spent a year traveling and taking jobs in Australia, including one under “harsh conditions” on a banana farm. He documented his metamorphosis from a baby-faced backpacker into a beatific adventurer.

Now he’s back in his home country, but he said, “My confidence is way up here now because I did things, I was alone — I’m way more open, I talk to strangers.” Mr. De Leo, now 21, lost nearly 30 pounds thanks to the highly active lifestyle, he said.

Because these working vacations often involve physical labor, the glow-ups frequently come with muscles and tans. But many attribute the “effect” to the more laid-back lifestyle and a sense of working to live, not the other way around.

A change of scenery can change the way we look and feel. “We absolutely are influenced by the systems and the environment and the context in which we operate, depending on how long we’re exposed to it,” said Melissa Doman, an author and organizational psychologist in Denver who specializes in workplace mental health.

Women are subject to the Australian transformation as well. Magda Slavíkova, a 28-year-old photographer from Benesov, Czech Republic, said she went from wearing fashion-conscious clothes and a full face of makeup to almost no makeup (since “you’re basically tanned all year round”) and a bucket hat. “I’ve simplified my wardrobe,” she added. “With the amazing weather, you don’t really need many clothes.”

Andre Ali of Schaffelberg, Germany, first visited Australia as an exchange student 10 years ago. He came back for college and will be eligible for permanent residency this year. Since moving, Mr. Ali, 35, has sported surfer hairstyles, but he said the most profound effect on him had been the sense of camaraderie. “You can stand in a line,” he said, and strike up a conversation “with anyone,” in contrast with German culture.

Haesung Kim, 25, traded studying microbiology in Samcheok, South Korea, for screen and film production at the University of New South Wales (and for longer hair). For him, the effect has meant “a strong mind-set and sense of self.”

Beverley Mitchell, 31, of Cork, Ireland, documented a similar transition. When she is not working as a traffic-control agent for mining companies in Western Australia, her lifestyle is “little bikini, bare face, barefoot,” as she put it.

But working holidays in Australia can be expensive. “It did take a while, obviously, settling to Australia,” said Ms. Mitchell, who quickly burned through her savings finding housing and work. “It’s a lot of stress that no one talks about.”

Ms. Doman, the psychologist in Denver, said she believed that overseas exchanges could benefit careers but that living abroad could be harder than it looks on social media. “You can have that initial sparkly feeling when you first get there, but then when the day-to-day living kicks in, that allure can go away quite quickly,” she said.

Ms. Mitchell, however, has no plans to return to Cork. For her, the Australia effect could become permanent.

The post Are They Hot, or Is It the ‘Australia Effect’? appeared first on New York Times.