Belzoni, Mississippi, a town of about 2,000 people, is known as the “Catfish Capital of the World”; it is also known as the site of one of the first civil-rights-era lynchings. On May 7, 1955, two members of the local White Citizens’ Council shot into the cab of Reverend George Lee’s car; the bullets ripped off the lower half of his face. Lee had been a co-founder of the town’s NAACP chapter and the first Black person to successfully register to vote in Humphreys County since Reconstruction. He’d also registered about 100 of his fellow Black citizens to vote, a remarkable feat given Belzoni’s size and the ever-present threat of violence against Black people throughout the South who dared to exercise their franchise during the Jim Crow era.

The Mississippi NAACP, led by Medgar Evers, began to investigate the death as a murder. But the county sheriff rejected the idea that there had been any foul play, instead suggesting that Lee had died in a car accident and that the lead bullets detected in his jaw were simply dental fillings. The local prosecutor refused to move forward with the case, and the white men went free.

I learned this story recently, after visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice—known to many as the National Lynching Memorial—in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial consists of more than 800 rectangular steel pillars, each representing a different county in which a lynching took place. One of them is Humphreys, in Mississippi.

[From the June 2024 issue: The lynching that sent my family north]

It was a cold, rainy day, and my first time seeing the memorial. The space is haunting in its stillness, and overwhelming in its scale. Some of the steel pillars are suspended from above, while others are closer to the ground, forcing you to walk among them, through a steel labyrinth of racial terror.

A man named Lee Perkins was also at the memorial that day, being pushed around in a wheelchair by his son-in-law Chris Brown. Perkins was born in Belzoni in 1937. He was 17 when the lynching took place. As he told me about growing up as a Black child in the Mississippi Delta, he looked up, his eyes tracing the pillars’ long, still bodies. He had a coarse voice with a warm southern drawl. “I never thought I would see something like this,” he said, his neck craning to read the names on each piece of steel. Dusk began to settle around us, and the sky slowly darkened at its edges.

“I pray to God they never get rid of this history,” Brown said. “We as a Black race went through so much, and they’re trying to erase that.”

The lynching memorial has two sister sites in Montgomery—the Legacy Museum, which traces the history of Black oppression in America from slavery to Jim Crow to mass incarceration, and Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, a 17-acre site that uses both contemporary sculptures and original artifacts to illuminate the lives and experiences of enslaved people. All three were created by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit legal organization founded in 1989 that has expanded into narrative and public-history work over the past decade and a half under the leadership of its founder and executive director, Bryan Stevenson.

Stevenson began his career as a public-interest lawyer, and went on to argue in front of the Supreme Court on five occasions, winning favorable judgments in all but one. He successfully argued, for example, against mandatory life sentences without parole for children, and for incarcerated people with dementia to be protected, in some cases, from execution. But he has said that as time passed, he came to understand that his legal work would not be enough on its own to effect meaningful criminal-justice reform. The American public, he felt, needed a deeper understanding of how the realities of the country’s history shaped the present-day system.

The Legacy Museum, which opened almost eight years ago, is perhaps the closest thing America has to a national slavery museum. Crucially, however, it is completely privately funded, receiving no state or federal financial support. As such, Stevenson and his colleagues are unburdened by executive orders; they need not bow to pressure to alter an exhibit after a presidential Truth Social post. I wanted to get a sense of how visitors were experiencing the museum and memorials now, when so much of what they depict represents the very history that the Trump administration aims to de-emphasize—if not outright erase—at schools, historic sites, and museums across the country. I also wondered how Stevenson thought about the role these spaces play today, compared with when they first opened, and what kinds of knowledge he hoped they might be able to provide to the visiting public as the country and its politics change around them.

Erasure was a recurring theme among the people I spoke with in Montgomery. On the opposite side of the memorial, I met two Black women, Jackie Brown and Annette Pinckney, who were also visiting for the first time. “We’re from Florida, where you have Governor Ron DeSantis, who is trying to erase our history,” Pinckney said.

Pinckney is an assistant principal at a high school in South Florida, and she has seen firsthand the impact of the state’s recent laws—such as the Stop WOKE Act—that regulate how schools and businesses deal with issues of race and gender. The Florida Department of Education has also banned AP African American Studies from being offered in Florida high schools, claiming that the curriculum lacks “educational value and historical accuracy.”

Earlier in their visit, Pinckney and Brown had stood inside a real former slave cabin located along the Alabama River, on which thousands of enslaved people had once been trafficked. They described feeling the biting wind whistle into the cabin through holes in the wood-panel walls, and thinking about how susceptible to the elements the family staying inside would have been. Pinckney wrapped her arms tight around her chest. “That right there was just gut-wrenching,” she said. “It makes it more real.”

The visceral experience they had is precisely the point, Stevenson told me. When we met that evening at the EJI office, Stevenson said that the goal of the sites is to force visitors to confront the violence of the past without the counterweight of a more uplifting narrative to assuage their distress. The sites were built with the aim of not repeating the triumphant progress narrative found in some other civil-rights museums, which, as he put it, “would rather tell a story of achievement than a story of continuing struggle.”

“I love those museums,” Stevenson said. “But if people are allowed to walk out thinking, Oh, isn’t that great that we had that civil-rights movement, and that took care of racism in America, that ended the struggle over voting rights, that ended the struggle over integration and access—if we do that, then we’re undermining the effort to achieve racial justice.” Many civil-rights museums rely on resources from state and federal governments, and Stevenson wonders if some of them feel pressure to tell a story that will satisfy those funders.

For many visitors, the EJI museums have become a site of pilgrimage, which has made them a major driver of tourism to Alabama. The museums are consistently one of the two most-popular paid attractions in the state (the other is the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville), and they receive about 500,000 visitors each year. “Eight hotels have been built in this city since we’ve opened, and airports have record levels,” Stevenson told me.

Another Black-history museum that serves as a site of pilgrimage is the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., which opened two years prior to the Legacy Museum. Stevenson said that the Smithsonian museum is an essential presence on the National Mall, and that it is more comprehensive than any other museum on Black life in the country. He worries, however, that it, too, can allow some visitors to leave with an incorrect impression of unalloyed triumph. This is in part, he believes, the result of how the museum was designed. Because its primary sections on the oppression and violence that Black people were subjected to during the Middle Passage, slavery, and Jim Crow are below the museum’s street-level entrance—while the culture exhibits are upstairs—the history exhibitions are effectively optional for visitors.

According to museum employees Stevenson has spoken with, this design choice poses an educational challenge. “They have a lot of school kids and a lot of groups that come in, and they get in the elevator and they go straight to the upper floors. They want to see Michael Jackson’s coat, and Michael Jordan’s shoe, and B. B. King’s guitar, and then they want to see the stuff on Obama, and then they want to go have a meal,” Stevenson said. In Montgomery, he explained, “it was important to create a narrative journey where you don’t have the option to avoid the hard stuff.”

Still, the hard stuff is a big enough part of the Smithsonian’s offering to visitors that in August, the Trump administration announced it would be undertaking a review of the institution and demanded that the Smithsonian turn over troves of documents including an inventory of all permanent holdings, all internal communications relevant to the approval of exhibitions and artwork, and information regarding 250th-anniversary programming. A week later, on social media, the president castigated the Smithsonian museums for supposedly having an undue focus on “how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been.”

Stevenson insists that the goal of the Legacy Museum is not to present Alabama as irredeemably racist or forever entrapped by its past. Alabama is a state that he loves. It is his home. He believes it can be different in the future, but not if people turn away from the past. “I don’t think slavery should define Alabama,” he said. “And if we have the courage to talk about it honestly, it won’t. But we can’t not talk about it and have a proper understanding of who we are.”

At the Legacy Museum, which is built on the site of a cotton warehouse where enslaved people were once forced to work, some of the first items you encounter are clay sculptures depicting the heads of captured Africans rising from the earth, many with chains around their necks, as digital ocean waves crash on screens behind them.

Through detailed explanations of the role that slavery played in every region of early America, you learn that Delaware passed a law prohibiting free Black people from moving to the state. You learn that in 1730, almost half of all white residents of New York personally owned an enslaved person. You learn that by the mid-18th century, enslaved people made up 70 percent of Charleston’s population.

In the next room, ghostlike figures projected onto the walls sing in re-created slave pens. I stood next to a man and his young daughter in the long hall lined with cages as we watched a phantom woman sing the chorus of a haunting Negro spiritual. The girl leaned into her father’s side and wrapped her arms around his waist as he held one hand on her shoulder.

After the Legacy Museum’s series of exhibits on slavery, visitors encounter a section that focuses on how the decades following emancipation were less a period of unfettered upward mobility for Black Americans than one of widespread, sustained racial terror—which often came in the form of lynchings. One of the most affecting displays is a wall lined with hundreds of jars of soil excavated from sites of lynchings across the country. As I walked by the jars, I was struck by how the color and texture of the soil in each one was different.

The soil from the site of Will Archer’s lynching in Carrollton, Alabama, on September 14, 1893, was cinnamon-red and gravelly.

The soil from the site of Marshall Boston’s lynching in Frankfort, Kentucky, on August 15, 1894, was light brown and rocky.

The soil from the site of Odis Price’s lynching in Perry, Florida, on August 9, 1938, was black and fine as sand.

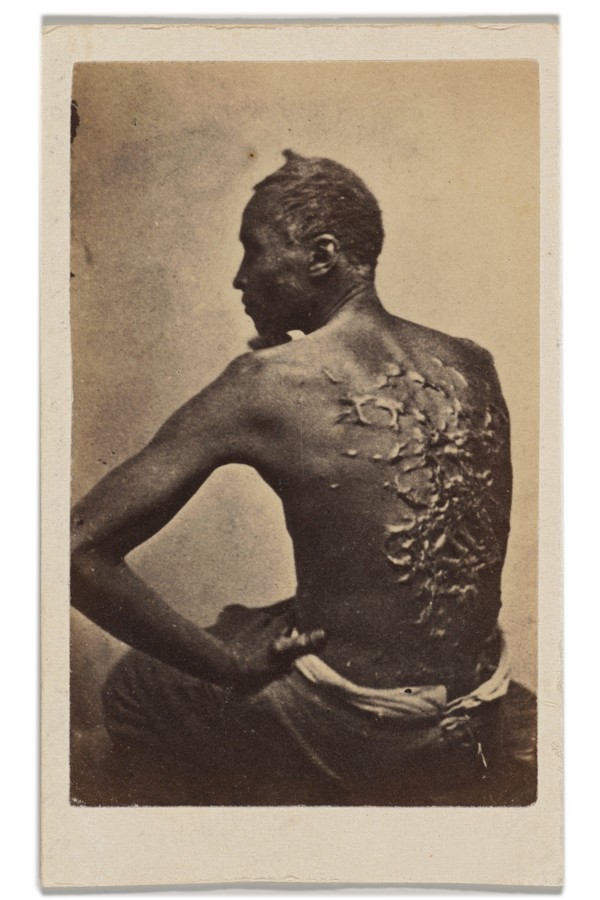

One of the Legacy Museum’s walls shows a floor-to-ceiling image of the infamous “Scourged Back” photograph, which depicts the horrifyingly scarred back of a formerly enslaved man named Peter who had received violent beatings. It was taken and published in the spring of 1863, in the midst of the Civil War and not long after the Emancipation Proclamation. The photo first circulated in northern cities in the form of small prints known as cartes de visite. When Harper’s Magazine published it in its July 4 issue, many Americans saw, for the first time, the physical violence wrought by slavery. The photograph boosted the abolitionist cause and challenged the widespread notion that slavery had been a benevolent and gentle institution. Since then, it has become one of the defining images of the brutality of enslavement, and has appeared in countless textbooks, museums, and magazines.

The photo’s presence in the Legacy Museum was particularly conspicuous at this moment. In September, The Washington Post reported that the same photograph had been removed from a national park in accordance with a Trump-issued executive order.

Less than a mile away from the Legacy Museum is the First White House of the Confederacy, where Jefferson Davis and his family lived in the breakaway nation’s earliest days. This White House receives substantial funding from the state of Alabama, and its mission is codified in Alabama state law: “the preservation of Confederate relics and as a reminder for all time of how pure and great were southern statesmen and southern valor.” In 2023, the Associated Press reported that people who visited the museum, including thousands of Alabama schoolchildren, weretaught that President Davis had led a “heroic resistance” in the “war for southern independence” and was “held by his Negroes in genuine affection as well as highest esteem.”

[Clint Smith: Actually, slavery was very bad]

“When I moved to Montgomery in the ’80s, there were 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy in the city,” Stevenson told me. And despite Montgomery being among the most prominent slave-trading cities in America leading up to the Civil War, “you could not find the word slave, slavery, or enslavement anywhere in the city landscape.”

I asked Stevenson if he thought the United States should have a public, national museum, in addition to the Smithsonian’s NMAAHC, dedicated specifically to slavery, or if it was better to have privately funded institutions like the Legacy Museum focus on that history. He paused and considered the question.

“I’m not sure we’re ready for a state-sanctioned truth telling about the history of slavery,” he said. “We can have a state-sanctioned space, but I don’t know why we would expect it to be a truth-telling space.” He pointed his finger down on the table. “Because the reality is we’re not yet at the point where, some would say, it’s in the state’s interest to be truthful about this history, so it would take a lot to get that truth to come through.”

Touring the Legacy Museum that afternoon, I’d seen a Black family with three children standing in a long hallway that outlined the chronology of Black life in America. The two older siblings ambled from one photo and caption to the next, while the youngest, a boy of about 7 years old, stood with his parents and read the captions out loud as his mother helped him through the words he couldn’t pronounce. They came to an image of a young white boy, about the same age as the Black boy, standing beneath the dangling feet of a Black man who had been lynched from a tree. The man’s face was cropped out of the photograph. The boy in the museum locked eyes with the boy in the image. I heard his parents tell him that sometimes children attended lynchings as well. The father stroked the top of his son’s head, and they walked on.

The post The Power of Private Museums appeared first on The Atlantic.