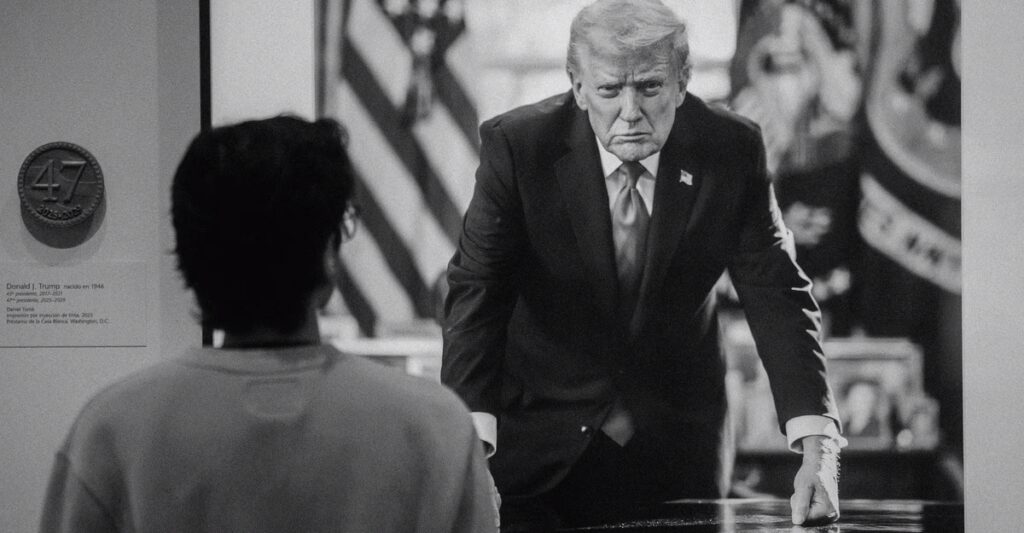

“Why does he look so angry?” one visitor to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., asked our guide, as if that were a question with an answer. The docent had finally stopped before the black-and-white photograph of a looming, glaring President Trump that dominates the entrance to the final rooms of the “America’s Presidents” exhibit. We had managed not to talk about him for several minutes, swerving left toward the bright, kinetic John F. Kennedy painted by the abstract expressionist Elaine de Kooning and then crossing right to view Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama—a calm, floating, saintlike figure surrounded by leaves and flowers.

But the president with the gorilla posture, knuckles firmly planted on the presidential desk, had to be dealt with. Someone else in our group asked why the Smithsonian had capitulated to Trump. Two days earlier, The Washington Post had broken the news that the National Portrait Gallery, which is overseen by the Smithsonian Institution, had swapped out an older portrait of Trump for the current one and put up a terse “tombstone” plaque that notes only the photographer’s name, Trump’s date of birth, and his years in office. All of the other presidential portraits in the gallery are accompanied by long assessments of each presidency, its successes and failures. They cite Andrew Johnson’s and Bill Clinton’s impeachments, and the label beside the previous Trump photograph mentioned Trump’s impeachments, too—but the new one, of course, does not. (That other photograph and caption can still be seen on the gallery website.)

Like some demonic trickster of folklore, Trump moves through the world robbing it of speech. The question about the Smithsonian’s capitulation left even our docent, a well-informed man, at a loss for words. He couldn’t address that, he said, but he could tell us a great deal about the desk in the Oval Office that Trump is leaning on: It is called the Resolute Desk because it was made from the oak timbers of the H.M.S. Resolute, a British Arctic-exploration ship.

The National Portrait Gallery spokesperson, noting that the museum had rotated in new Trump portraits before, dismissed the tweaks as routine. But when it comes to Trump and the preservation of historical memory, nothing is routine. The administration began pressuring the Smithsonian for changes almost as soon as Trump returned to office. In March, he signed an executive order demanding that the Smithsonian review its exhibitions for “improper ideology.” In May, Trump forced out the National Portrait Gallery’s director, Kim Sajet, on grounds of excessive partisanship. (He tried to fire her even though that was not within his power, and she resigned.) At the time, the White House wrote up its objections in a list obtained by The New York Times; one complained about the allusions to his impeachments. In July, the National Museum of American History took references to Trump’s impeachments out of its presidential exhibit. These were restored in August, but in watered-down form. Meanwhile, the National Portrait Gallery has said that it’s planning a larger “refresh” of the “America’s Presidents” exhibit and is exploring putting more tombstone labels there and elsewhere.

Many bad things are happening in America right now, and the suppression of wall text in an art museum, even a quasi-governmental one, is far from the worst of them. Yet both the uninformative label and the new portrait are worth lingering on, for two reasons. First, the fact that Trump’s impeachments were censored, and nothing else at the National Portrait Gallery has been—that we know of—is a reminder that although the administration couches its assaults on American institutions as a campaign against “wokeness,” what the president really cares about is his own reputation.

[Read: Looks like Mussolini, quacks like Mussolini]

Second, Trump is a man who spends a lot of time shaping his image. Many unusual artistic choices had to be made to arrive at the official White House photo of his second administration, a snarling headshot lit from below that plays off the mug shot taken at the Georgia jailhouse in 2023, when Trump was booked on election-racketeering charges. (The official photo hangs in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.) “He’s very hands-on,” Shealah Craighead, the chief White House photographer during the first Trump administration, told The New York Times for an article about the inaugural photo. When Trump swapped photographs in the National Portrait Gallery, he was sending a message. Decoding it provides some small insight into why he feels the need to look so angry—though I suspect we’ll never understand that completely.

The first president in the “America’s Presidents” gallery is, of course, George Washington. His portrait was painted in 1796 by the artist Gilbert Stuart, who may be more famous for a different portrait of Washington, which became the face on the $1 bill. With this work, however, Stuart effectively invented the presidential portrait.

To the contemporary eye, Washington looks uncommonly grand; indeed, the style of composition is known as grand manner. The painting shows the full figure of the great leader, his already-large frame—he was more than 6 feet tall—exaggerated by a bigger-than-life 8-by-6-foot canvas. He stretches out his hand in the classical gesture of a man making a speech. (Stuart is thought to have based the pose on Washington’s 1795 address to Congress.) The furniture in the room is ornate and gilded. Lace cascades from his cuffs and neck. He holds a gold-handled saber.

But an 18th-century viewer familiar with European royal portraiture would have understood that even as Stuart was invoking its conventions, he was also defying them, endowing Washington with the authority of a head of state while differentiating him from a king. The historian David C. Ward calls the portrait “an explicitly antimonarchical work of art.” In lieu of regal robes, the president wears a plain black suit. Compared with the mighty swords that dangle by the side of European rulers, his saber is barely noticeable. The Federalist Papers rest on top of the table, the U.S. Constitution below. (The guide pointed out the Constitution, adding, “I’ll let you think about that.”)

[Read: The pitiful childishness of Donald Trump]

Washington’s most presidential feature, though, is his expression. His lips are pressed into a faint grimace, but his eyes are calm and steady, gazing into the distance as if toward the future. This is not another proud autocrat, but an ardent visionary who is tamping himself down so as to model neutrality. He is a republican, which is the point. In a shaky union still divided over the question of federation, he unifies rather than divides; he may have led the nation in war, but here he seeks peace. The circumspect Washington embodies the ideal of government that had recently been put forth in The Federalist Papers: the maintenance of equilibrium through judicious balance. In the state, the balance is one of powers; in the statesman, it is of feelings about power. Here is a president who would know to step down after his second term.

Washington’s portrait sets the emotional tone of the exhibit; he is the benchmark of presidential temperament. Stuart also painted the half-length portrait of Thomas Jefferson, whose lips form the same tight line. His brow is heavier, though, and his eyes half-hooded. He seems remote, unknowable—a complicated man. James Madison has sagging jowls and a mournful gaze turned up toward God, suggesting that the co-author of The Federalist Papers had considerable gravitas. Aesthetically, the best portrait is that of Grover Cleveland; it also makes him very likable. Cleveland sits at a table messy with books and papers, leaning on one arm and looking up as if listening attentively. His legs are spread wide to accommodate his girth, and his expression is frank and open. He could be one of Frans Hals’s friendly tavern-goers.

The captions steer us toward interpretations of presidential affect. James Buchanan looks prissy and irresolute, especially after we learn that he “did little to prevent the first seven Southern states from seceding,” and that the Civil War broke out “only a few weeks after he had left office.” Gerald Ford faces us squarely in the canonical stance of the decent man. He granted amnesty to both Richard Nixon and Vietnam-draft evaders, and is the first to smile—faintly—in his presidential portrait. By the time we get to George W. Bush, the norms of self-presentation have relaxed even further: He sits on a low couch in his shirtsleeves. His uncertain electoral victory and failure to mitigate the effects of Hurricane Katrina make him sound like a lightweight, and his smile verges on pleading.

Only one other president projects anything like Trump’s aggression. That is a seated but powerful Theodore Roosevelt, his gaze fierce and his walrus mustache seeming to emphasize a downward turn of the lips. One hand clutches a riding whip; the other is balled into a fist. “An outsize personality who preached the benefits of the ‘strenuous life,’” the caption reads, “while also being among the most learned of presidents.”

[Read: The wannabe tough-guy presidency]

The Trump photograph that was installed this month, however, occupies a whole other political universe—just like its subject. It is the third to go on display at the National Portrait Gallery during his second administration; he scowls in all three of them. (The scowl is “his favorite pose,” Craighead, the former White House photographer, also told the Times. “He doesn’t want to smile because it seems weak, is probably what he would say.”)

In the first of this term’s photos, displayed in early 2025 to mark his inauguration, Trump is seated at his desk and turns to look at us. We seem to be standing to his right, almost as his equals, and his left hand rests on the desk. In the second portrait, his dark suit recedes into a dark background, highlighting his loud red tie, but he clasps his hands calmly in front of him. To spot changes in the pitch of Trump’s ever-present bad temper, you have to look at the hands. That he leans into his fists in the portrait that is now hanging in the presidents gallery says everything you need to know. In the absence of curatorial guidance, nothing shields us from his naked belligerence. He invades the space and overpowers the viewer. I thought of ICE occupying blue-state cities. I felt certain that I was supposed to, though later I wondered whether I was supposed to think at all.

The photo informs us, wordlessly, that we have come under the rule of a monarch, and not just a monarch: a would-be tyrant. We don’t know what images, if any, influenced the photographer, Daniel Torok, but somewhere in the background lurks Hans Holbein the Younger’s most famous state portrait, a full-frontal depiction of Henry VIII, who, after he broke with the Catholic Church, became the head of his own church, laying claim to God-given authority.

The original Henry VIII portrait, painted in 1537, formed part of a mural that was lost in a fire, but in most of the copies made over the centuries, the king’s swollen face and massive body overwhelm the frame. A comically large codpiece pokes out between the folds of his skirt. One hand fingers the strap of a hanging dagger, and his eyes fix the viewer with a cold, appraising stare. Henry was egotistical and ruthless, and executed almost everyone who opposed him; the fierce, blunt portrait is said to have terrified his court. I’m sure he liked that.

The post Caption or Not, Trump’s Portrait Says It All appeared first on The Atlantic.