Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

In the late 1970s, after middle school let out, I would take a bus across Seattle to wherever my mother was working. Kathy Streeter was an office secretary then — what might today be called an executive assistant, mostly at the University of Washington. After a painful split with my father, she was navigating a hard, perilous stretch for our family, often stuck in jobs she was overqualified for. But when I remember those afternoons — sitting beside her desk, doing homework, listening to the staccato rhythm of her IBM Selectric — the feeling that returns is warmth. Security. The machines she favored were robin’s-egg blue, the keys tapping in a steady pulse that meant she was there.

My mom died in 2019, at 87, just before the pandemic sealed us all away from one another. As a writer, I had been circling the subject of typewriters for years. And when I sat down to report a story about a typewriter repairman in a small shop in Bremerton, Wash., a working-class Navy town, I finally understood why. Mom had always been my bedrock. I was reaching for her.

The story began with curiosity. I’d always appreciated typewriters, though I had barely used them myself. In college, I couldn’t type at all — I wrote papers longhand, and a friend transcribed them on a word processor. Still, those machines had left their mark, and I wondered if someone was keeping the old craft alive.

I found Paul Lundy in the fall of 2023. He ran a small typewriter repair business he had purchased from his mentor, Bob Montgomery, a wizened, reclusive man in his 90s who had worked on typewriters for more than half a century.

But as a national reporter at The New York Times, when the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel happened, the news demanded everything. I put down the story for more than a year as I covered the effects of the war in Gaza at home, the run-up to the 2024 election and the reshaping of Trump’s America. I might have dropped the typewriter repairman story entirely. But I couldn’t let it go.

When I returned to Bremerton, Mr. Lundy had moved his shop across the street, into a 115-year-old building with big windows facing the sidewalk. People wandered in, drawn by the machines in the window — some of them as old as the building itself — and Mr. Lundy invited them to sit and type. I watched them discover what I soon would myself: the physical pleasure of pressing into those keys, the click and clack, the heft of a machine built to last.

The slowness was a real draw — time seemed to loosen and melt compared with the compressed, precise, rapid-fire pace we’ve all grown accustomed to in the digital age.

Pulling me deeper was Mr. Lundy’s relationship and apprenticeship with Mr. Montgomery. Mr. Lundy had spent years in a well-paying job that had hollowed him out. He told me he had planned to retire the day he turned 65. Then he met Mr. Montgomery, and everything changed. He became a student again in his 50s, learning a trade from a man a generation older. The transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next — I remember turning that phrase over before I’d written a word.

It struck something personal. I’ve been shaped by people like that: an English teacher in high school who saw something in me; tennis coaches who pushed me through years of competition; later, a trio of journalists nearly 25 years my senior who taught me how to report long-form narratives, how to see, how to wait. I still go to one of them, now 83, for advice. The passing down of knowledge isn’t just a transfer — it’s a kind of love.

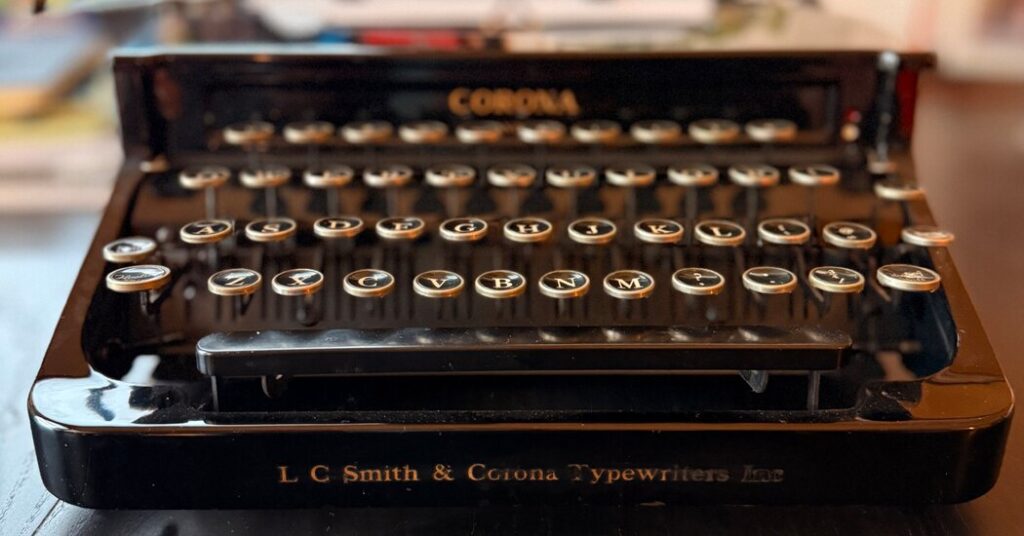

Mr. Lundy lent me a restored 1930s Corona, gleaming black with a fresh ribbon. I decided to type an entire draft of the story on it.

It took days. My pinkie fingers had atrophied after years of light tapping on laptops. But the real revelation came when my attention wandered. Every time my mind drifted — to lunch, to a workout, to some stray worry — I made a mistake. There was no delete key. I crossed out the error and started again. By the end, the pages were scarred with X’s, a literal record of inattention.

On screens, I can cut and paste, disappear down digital rabbit holes. The typewriter showed me exactly when I wasn’t present. It was humbling. Useful. It made me a better writer — or at least one who is more honest about how often my mind leaves the room.

I’m going to buy a typewriter from Mr. Lundy. Despite my fondness for the IBM Selectric, I want to dip further into the past. Maybe that Corona, maybe something from the ’50s that’s easier on the hands. I plan to use it for thank-you notes and letters to friends, the kind of writing that feels better when you know someone pressed each letter into the page.

I’ve always been drawn to stories like this one: the wisdom of elders, the search for meaning in midlife, all bound up in machines of remarkable engineering and beauty. But mostly, I wrote this story because I had to. For my soul. For the afternoons in that office, the blue machine humming, my mother’s hands on the keys. The sound that meant I was cared for.

Kurt Streeter writes about identity in America — racial, political, religious, gender and more. He is based on the West Coast.

The post In a Typewriter Repair Shop, a Reporter Finds a Familiar Hum appeared first on New York Times.