Step inside a Hollister store today, and get a millennial retrospective: low-rise baggy and flare jeans, baby doll tops, fur-trimmed cable-knit V-necks, and sweatpants with numbers and words like “Senior” printed on the backside.

Walk outside, and you may notice teens sporting Longchamp totes and Ugg slippers. Or digital cameras, which are seeing a resurgence after years of being sidelined by smartphones.

These are the markers of “Millennial Core” — or the “Y2K aesthetic,” depending on whom you ask — a Gen Z reimagining of the trends its elders (now roughly 29 to 45 years old) made mainstream in the late 1990s and early aughts. Though it’s not unusual for teens and young adults to resurrect styles of the past — fashion trends tend to have 20-year cycles — the current moment speaks to a yearning for what they perceive as simpler times, when people their age weren’t tied to their phones, endlessly strolling, and battling brain rot, industry experts say.

“It is such a foreign concept to Gen Z and younger because it’s a world they will never be able to experience,” said Jenna Drenten, a marketing professor at Loyola University Chicago. “Some of these consumer choices … are a tangible way of trying to capture some of what that culture was.”

Teens are taking cues from influencers and peers on social media. And brands are capitalizing on this, reacting quickly to emerging styles and sending products to TikTok stars to show off to their followers.

But it’s more than just staying on-trend — curating a modern Y2K style is both a creative outlet and a form of escapism for Gen Z, who run from approximately age 13 to 28, said Michael Tadesse, a marketing professor at George Washington University. During times of social, economic, climate and political instability, they search for “an emotional anchor.”

“So when they go to Coach, Longchamp and others, [the brands] are familiar, comforting and also safe to experiment” because older generations have shopped there, said Tadesse, who studies how technology and psychology shape marketing and retail. “Our brains are wired to find comfort in things that we’ve seen repeatedly.”

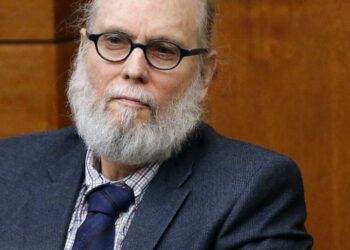

It’s no coincidence that Gen Z is drawn to these brands, said Mark Silverstein, the chief executive and co-founder of Cafeteria, an app that pays teens and young adults to offer their insights on brands, retailers and trends. The most successful brands are known for quality and value, do frequent-enough discounting and have physical stores. They also marry nostalgia with modern style, he said.

“If you don’t have all these elements, you’re not capturing this group,” Silverstein said.

The payoff is clear when you do: Birkenstock’s revenue rose 16 percent in fiscal 2025. Tapestry, which owns Coach, said net sales surged 13 percent last quarter, year-over-year. Notably, of the 2.2 million new customers it acquired globally during that time, 35 percent were Gen Z.

Hollister, which is owned by Abercrombie & Fitch, outperformed the namesake store in its last quarter, A&F chief executive Fran Horowitz said in a November earnings call. Same-store sales at Hollister grew 15 percent year-over-year.

Industry experts expect that this nostalgic style will only grow in 2026.

“It’s going from trend to acceptance,” Silverstein said.

Vicarious nostalgia

Though the idea of feeling nostalgia for an era you didn’t actually experience might be counterintuitive, Chris Beer said it’s a “constant rule” for marketers.

“Younger people are almost paradoxically more nostalgic,” said Beer, a senior data journalist at global insights company GWI. “It’s to do with life disruptions, and of course when you’re young you go through so many milestones and rites of passage.”

Drenten, who as a teenager in the late 1990s and early 2000s remembers her mom saying she had the same halter top at her age, calls it “vicarious nostalgia” when a cultural zeitgeist gets reformed for a new generation. But the difference now is that tweens, teens and young adults have more exposure to former trends and cultural touchstones than their predecessors, who had to draw inspiration from old photos, magazines, album covers and TV shows.

“Gen Z — and even Gen Alpha — has a much bigger access portal to this generational hand-me-down, which is the internet,” said Drenten, who studies digital consumer culture. “Now you have social media, you have search, Google and Pinterest.”

They can still find 2006 outfit inspiration boards on Pinterest with baggy, low-rise jeans, slim sunglasses, miniskirts and Ralph Lauren polos.

There are other triggers outside social media that are filtering into the marketplace, Drenten said, with current economic uncertainty amid a slowing job market and inflation, and geopolitical instability in the Middle East and Russia being reminiscent of the early 2000s: “There’s a bigger bubble or radius of where there’s millennial comparisons being made.”

Ironically, Silverstein said many of the teenagers and young adults his company surveys talk about a desire to “retreat to nostalgia” to get away from these conditions, as well as feeling chained to technology and AI that “are just flooding the internet with junk.”

They’re not just expressing Y2K aesthetic in their clothes and handbags — they’re also buying analog media such as vinyl, CDs and cassettes, as well as digital and disposable cameras, coloring books, charm bracelets, and collectible cards and figurines.

Though CDs and DVDs are still niche, revenue declines are leveling. Sales fell 3 percent in the third quarter of 2025, according to the trade organization Digital Entertainment Group; a year earlier, they tumbled nearly 26 percent.

But sales of point-and-shoot cameras climbed 48 percent, year over year, in the 52 weeks ended Jan. 3, according to market research firm Circana. The number of units sold spiked 89 percent.

“Waiting for a photo to develop, or download, or print, increases emotional reward,” Tadesse said. “It’s delayed gratification. … They’re trying to figure out a way to appreciate what they have because everyone’s told them that they want everything now, and life doesn’t work that way.”

Curators, not consumers

The brands with the most “iconic Y2K vibes” keep finding new ways to refresh the millennial look, Silverstein said. Ugg launched a line of Mini boots and its Tasman slipper. Birkenstock released more colorways and variations on its popular clogs and sandals. Hollister is constantly refreshing its in-store inventory. Other brands bubbling back up are Juicy Couture, Ed Hardy and True Religion, Silverstein said.

The teens and young adults Cafeteria surveys say these brands “‘get it’ as far as modern styling with the aesthetic,” Silverstein said.

Then there are brands such as Coach and Longchamp, Millennial Core staples that come with a level of “recognizable status,” he said. These shoppers may have spotted these brands in their mom’s closet.

The Coach Brooklyn purse — a popular tote that ranges in size — goes for $295 to $495. A Longchamp Le Pliage original tote bag costs $180.

“It’s expensive enough to signal quality and status, but there is this aspirational-purchase language they use around them: ‘I’m waiting to buy this,’ ‘I’m saving up for it,’ ‘I’m having it in my cart for the right time,’” Silverstein said. “They have identified the product they want. … It is the goal.”

The internet has played a crucial role in how Gen Z has adapted their style. They have endless inspiration and everything they could want on their devices, Tadesse said. Unlike millennials, who were mostly limited to discovering what was cool by reading the same magazines, watching the same TV shows and visiting the same stores in the mall, Gen Z is less constrained, and it’s reflected in their fashion choices, Tadesse said.

“They’re curators,” he said. “They’re able to mix and match, and do things their own way. And so that gives them the irony, the play and the ability to control traditional sense [of style], but they bring their own flavor of what’s cool.”

“Something that could be cringe is also cool,” he said.

The post How Gen Z is making millennials look cool again appeared first on Washington Post.