(3.5 stars)

In 1774, a small group of splintered-off Quakers from Manchester boarded a rickety ship to America, led by the visions of an illiterate woman named Ann Lee, whom they believed to be the second coming of Jesus Christ. Their intent was to flee religious persecution in England and bring the New World closer to God, via a faith whose central tenets included celibacy and gender equality, and a worship practice defined by shaking during prayer.

It was a hard sell — you try converting a bunch of followers by telling them they can never have sex again — but at the height of the Shakers’ popularity, there were around 6,000 adherents across the Northeast and Midwest, living in communes whose craftsmanship and architecture still influence American aesthetics today. When Lee, whose charisma and fortitude had guided the whole operation, died in 1784 at age 48, the number began to dwindle. Today there are only three Shakers left, and when they die, the faith dies, too.

This fascinating slice of history is long overdue for a biopic, but you probably never would have expected one that looks like “The Testament of Ann Lee,” which arrives at area theaters Friday. For one thing, it’s a musical. It opens with a group of women in period dress, slithering and leaping through a forest by way of Martha Graham-inspired dance moves as Sister Mary Partington (Thomasin McKenzie) solemnly explains that Lee was born on the 29th of February, “as you might expect from a miraculous person.” One colleague I know who saw an early screening confessed that the opening dance made her laugh to the point that she never really recovered, and I’ll admit, when it first happened on my screen, I wasn’t sure whether this was a comedy, a drama or a “Blair Witch” situation.

But I implore you to sit through the early minutes, because what unfolds is a luminous, transporting, deeply strange and deeply human examination of faith and vision. It’s quite unlike anything you’ve seen, but sure-footed enough to convince you there was no other way to tell this story.

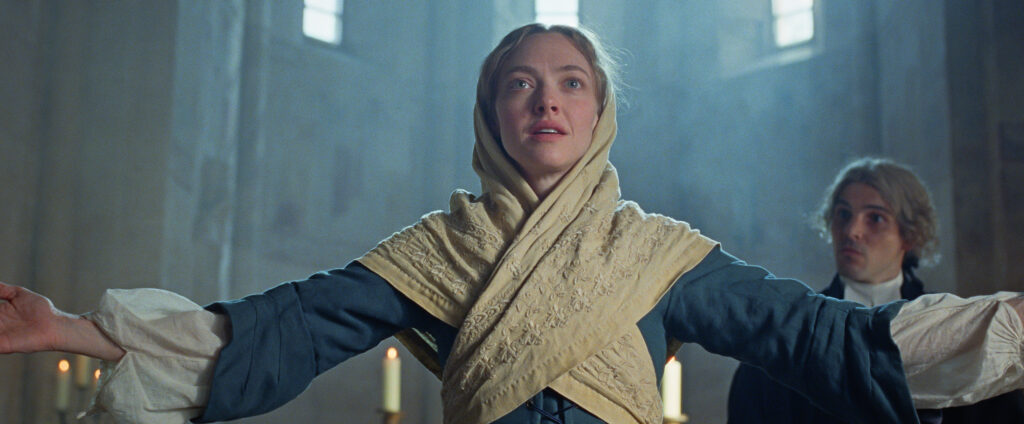

Ann Lee is portrayed rapturously by Amanda Seyfried in what is certainly the performance of her — or anyone else’s, for that matter — career. She plays the leader without an ounce of cunning or ego, a pure soul starving for genuine meaning and closeness to God, which only deepens after her already-unhappy marriage deteriorates and she loses each of her four children before their first birthdays (these scenes are unflinching, as a trigger warning to anyone who has ever experienced stillbirth or child loss). She turns to Quakerism, finding catharsis in the dynamic, physical prayer style of the meeting run by Jane and James Wardley (Stacy Martin and Scott Handy). But after the death of her last baby prompts a stint in the insane asylum, she emerges to say that God has revealed to her that sex is the root of all evil. Salvation is possible only via avoiding it.

A more traditional movie might have let this drama unfold with a raised eyebrow, an acknowledgment to the audience that Ann’s testament sounds crazy and so she must be a huckster, a charlatan or mentally ill. But director Mona Fastvold, who co-wrote the script with her romantic partner Brady Corbet, chooses instead to let us believe. When Ann sees a vision, we see it, too, in a collage of bright colors. Her predictions often come true. She requires hard work and sacrifice of her followers, but no more than she is willing to give herself, all toward building a faithful community that bestows upon her the title of “Mother.”

Many religions are perpetuated by male ego — the conquering, the crusading, the fact that God seems to tell so many of them that righteous husbands need multiple wives, but nobody ever receives a burning bush message suggesting that wives should take multiple husbands. But in “The Testament of Ann Lee,” we are given the rare chance to watch an exploration of a religion born instead of female pain.

Is it any wonder that a woman whose only sexual experiences were brutish and traumatic — in the film, at least, a selfish husband with a spanking fetish that Lee does not share — would envision a faith in which celibacy is divine? That a woman whose children had all died in infancy would embrace a maternal honorific from an ever-growing flock of believers? That, when her gender prohibited her from participating in much of society, she would be drawn to any biblical passages implying that God made women to be as worthy as men? The Book of Revelation describes “a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon beneath her feet, and on her head a crown of 12 stars.” Classically, this was interpreted as a metaphor for the church; the Shakers decide it refers specifically to Lee.

“The Testament of Ann Lee” does not present the Shaker faith as perfect. Most practically, it’s difficult to build a denomination that, lacking the natural growth mechanism of procreation, must be made entirely of converts. But the imperfections here are different from the kinds we typically see in stories of visionary men. Fastvold and Corbet’s most recent collaboration was “The Brutalist,” which they co-wrote but Corbet directed. It was a similarly sweeping character study, and also a specifically observed masculine film. With Fastvold at the helm, we see the same specificity and confidence tuned toward a very feminine work. How richly satisfying to see a film where the strongest relationship is between a woman and her spiritual journey.

There are many strong performances in “Testament,” most particularly Lewis Pullman (Bill Pullman’s son) as Lee’s brother and faithful deputy and David Cale, the film’s only real comic relief, as the financier who makes the voyage to America possible. But aside from Seyfried’s electric, captivating turn, the two players most worthy of mention do not appear on-screen at all: choreographer Celia Rowlson-Hall and composer Daniel Blumberg.

The dancing in “Testament,” presented mostly as an expression of prayer rather than performance, is rarely beautiful but never uninteresting. Once you move past the woodland Martha Grahams, characters beat their chests, whirl in circles, and trace and pace the floor in sequences that are ecstatic, tender and heartbreaking. The movements are less choreography than an extension of the soul: A sequence in which Seyfriend cradles her own foot as if it were a baby is the most visceral moment I’ve seen on a screen all year; a sequence in which the group of nine dances together during their voyage across the Atlantic feels almost holy.

As the characters dance, they often simultaneously sing. Blumberg reworked several classic Shaker hymns for the film into a haunting, propulsive soundtrack. “I Hunger and Thirst” was written in 1837; when it is sung by Seyfried and other characters, it becomes a modern ballad of deep, delicate yearning. “All Is Summer” is a perfectly lovely hymn in its original form; in the movie, it becomes mystical and otherworldly.

The nine traveling Shakers sing it as their ship crashes against waves, takes on water, nearly sinks again and again. At one point, the captain tells everyone they will be drowned by morning. Ann Lee tells him not to worry. She has seen the future. They are destined to make it across the ocean safely; they are destined to save the world.

R. At AFI Silver Theatre. Contains sexual content, graphic nudity, violence and bloody images. 137 minutes.

The post ‘The Testament of Ann Lee’ dares to make religion feminine appeared first on Washington Post.