Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

Max Bearak was in a taxi leaving El Dorado International Airport in Bogotá, Colombia, when he got the call.

It had been just two days since the U.S. military swooped into Venezuela and captured its president, and just one day since President Trump, aboard Air Force One, implied to reporters that Colombia’s leader, Gustavo Petro, could be next.

Mr. Petro was a “sick man” involved in drug trafficking, Mr. Trump said, without evidence. And as for military action against Colombia? “Sounds good,” he added.

The call was from one of Mr. Petro’s closest aides.

“Mr. President wants to speak with The Times,” the aide said. “He wants to clarify some things.”

A president requesting an interview, rather the other way around, is rare. It is an even rarer opportunity to be able to sit with a head of state who has just been called out by the U.S. president. Mr. Petro and Mr. Trump, who had never spoken before, had spent much of the past year butting heads, mostly on social media, on topics ranging from deportations and U.S. boat strikes to Gaza and climate change.

Little did we know how unusual the next 72 hours would be.

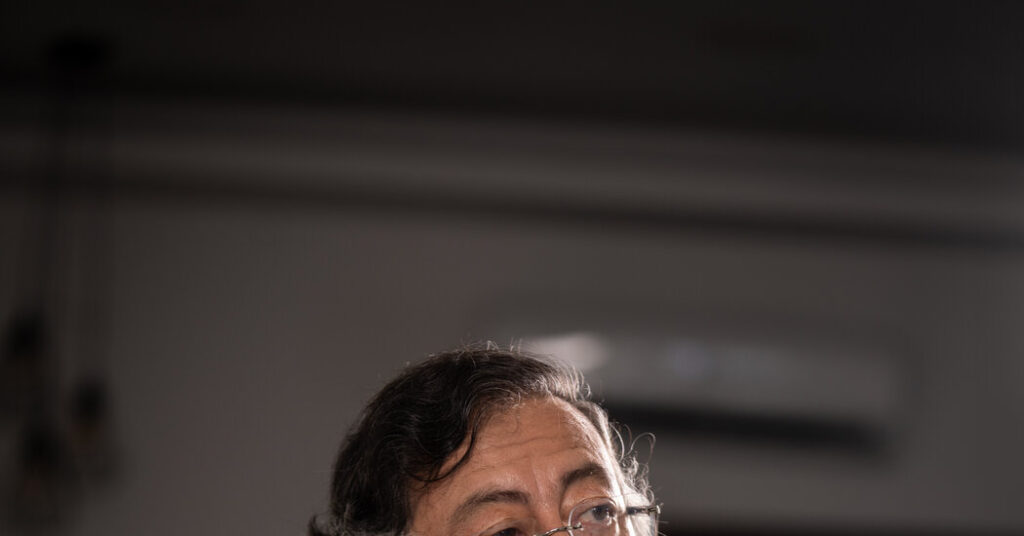

Unusual is a word well-suited to Mr. Petro. He is a former Marxist guerrilla leading a staunchly religious country whose citizens are exhausted by decades of armed conflict. Nearly all his predecessors could be called conservatives, both in dogma and style, and the white linen guayaberas he often wears are a stark contrast to a longstanding protocol of cashmere sweaters and slacks.

We were instructed to be in the seaside city of Cartagena as early as possible the next day, where the interview was to take place on a naval base. Once there, with little time to prepare, we were asked to set up our chairs, lights and cameras on a large balcony attached to a mess hall.

Under swaying coconut palms, we wilted for eight hours as the sun crossed the sky and as Mr. Petro delayed and delayed the interview. Sweat stains mottled our shirts. While we waited, we checked our phones, watching his foreign minister declare the armed forces would respond if attacked, and as he posted more than a dozen ideology-laden screeds on X.

In one post, he wrote that Mr. Trump’s attacks against him were symptomatic of a “senile brain.” In others, he referred to the “jaguar” that had been awakened in the heart of the Latin American people by U.S. imperialism.

Our interview was postponed until the next morning, but we were given an odd reason for its delay. We were told an unauthorized foreign boat had been spotted in Colombian waters, and Mr. Petro was overseeing the response. It later proved to be a rumor, but like his cascade of messages on X, it made one thing abundantly clear: Mr. Petro was seemingly jumpy and acting as though he were being backed into a corner.

When we finally met Mr. Petro the next morning, he appeared groggy, as if he had been up all night. In our interview, his thoughts were coherent but rambling. He spoke for nearly two and a half hours, most of which he devoted to lessons on Colombian history, from centuries-old slave rebellions to the time the United States “invaded” Colombia to annex Panama and build the canal. He insisted these lessons were crucial to understanding the present standoff with Mr. Trump. (We resumed wilting — his aides had turned off the air conditioning because Mr. Petro had frequently complained that cold air gave him sore throats.)

In brief asides, he acknowledged the looming threat to him and his country. “We are in danger,” he said. Fearing he himself might be targeted by the U.S. military, he told us, he would sleep in the presidential palace in the capital, Bogotá, next to the sword of Simón Bolívar, the South American independence hero.

At that very moment — in Washington and Bogotá — plans were being made that would upend this trajectory, but it appeared Mr. Petro did not know that as our interview wrapped up. As soon as we shook hands with him, his guards rushed us to the presidential plane, a 20-year-old Boeing 737.

We assumed the rush was because Mr. Petro had called on Colombia’s people, on X, to take to the streets to defend the nation, and he was to speak at what promised to be a big rally in Bogotá. It turned out that a diplomatic effort by Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, a Republican, and by Colombia’s ambassador in Washington had yielded a “yes” from President Trump, who had agreed to a phone call with Mr. Petro that afternoon. It would be their first direct communication ever.

With that call, it was clear that our history lesson from earlier that day, was, well, history. Whatever happened on the phone call would be the news.

As it happened, along with Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and other officials, our colleagues from The New York Times were in the Oval Office with Mr. Trump, while Mr. Petro was on speakerphone, though the contents of the call were off the record.

At first, we were able to gather what had transpired only through Mr. Trump’s warmly worded post on Truth Social, in which he wrote that it was a “Great Honor” to speak with Mr. Petro, whom he invited to Washington. An aide to Mr. Petro said the call had “gone well” and little more.

Mr. Petro delivered the same news to rally-goers who had been waiting hours for him, to thunderous applause.

That evening, an aide called to invite us for another interview with Mr. Petro.

The next afternoon, in the presidential palace, the Colombian leader said something that, given our experience in Cartagena, didn’t surprise us at all: He had spoken for most of the 55-minute call with Mr. Trump. He expatiated on the intricacies of Colombia’s long war against the drug cartels, allowing Mr. Trump to speak only as the allotted time for the call neared its end.

Max Bearak is a reporter for The Times based in Bogotá, Colombia.

The post Interviewing Colombia’s President, Before and After His Call With Trump appeared first on New York Times.