It is a critical part of every chief executive’s job to anticipate the future. Failing to recognize and adapt to change can be the difference between thriving or disappearing. That’s why corporate leaders are continually bracing their companies against a host of possibilities: another pandemic, global conflict, rising interest rates, climate change and competitors that arise from nowhere.

But it is pretty difficult to futureproof your company against stupid.

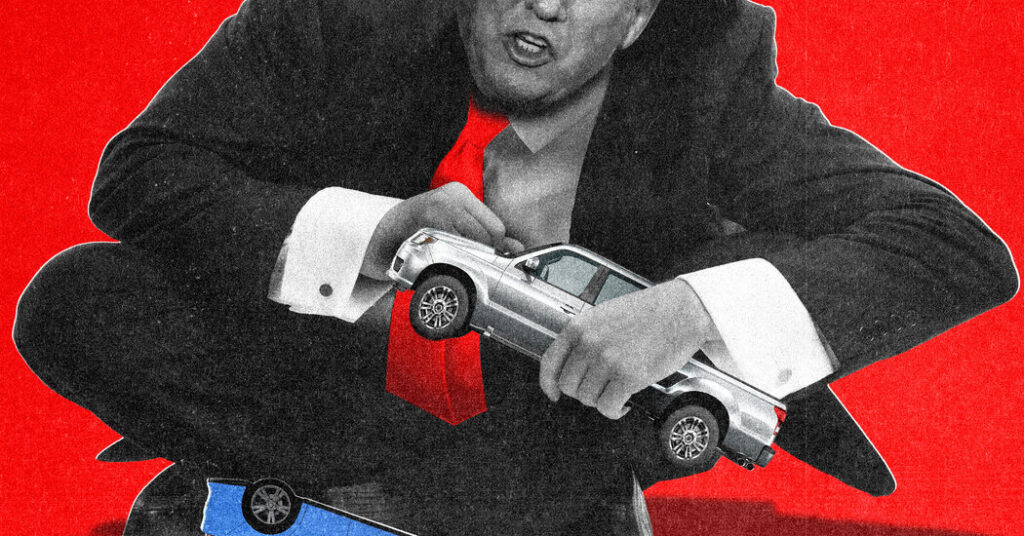

This is exactly what the American automobile industry is facing as a result of Donald Trump’s gratuitous war against electric vehicles, which is forcing manufacturers to return to an increasingly outdated past. Ford Motor has mothballed production of the all-electric version of its flagship F-150 pickup truck, and last month announced a $19.5 billion charge related to restructuring its E.V. business. General Motors, citing the loss of tax incentives for E.V. buyers and laxer pollution regulations, switched production at its Orion, Mich., plant from E.V.s to full-size S.U.V.s and pickups powered by internal combustion engines (ICE, in industry parlance). In doing so, G.M. last week announced that it was taking a $6 billion loss in the fourth quarter — on top of a similar $1.6 billion hit the quarter before.

Pickups and giant S.U.V.s, Detroit’s bread and butter, have gotten the industry in trouble before. In 2008, the industry didn’t anticipate oil prices soaring. When they did, buyers abandoned gas guzzlers for thrifty Toyotas and Volkswagens. When the housing market collapse set off the Great Recession, G.M. was forced into bankruptcy and had to be rescued by a $50 billion bailout. Ford took a huge loan to save itself.

Detroit allowed the E.V. pioneer Tesla to become the most valuable auto company in the world. But then, the auto industry’s chiefs actually got it right: They accelerated their electric vehicle programs to meet the market and a greener future, ensuring that they would be part of a transformation that’s already happening globally.

About 25 percent of new cars sold globally are E.V.s. They now make up more than half of new car sales in China. In Norway, more than 90 percent of new car sales are E.V.s.

But American automakers got one key thing wrong: failing to anticipate how the business climate would change under Mr. Trump, whose tariffs raised their manufacturing costs and scrambled a trilateral supply chain built on autos, parts and subassemblies flowing freely among the United States, Canada and Mexico.

Mr. Trump’s efforts to undermine an obviously beneficial technology is something that, as far as I can tell, no large American company has encountered. Imagine a president who decrees that all music has to be sold on vinyl rather than digital. Maybe Mr. Trump will try to ban cruise control, too.

One big reason for Mr. Trump’s rejection of E.V.s is simple: President Joe Biden championed them as his administration pushed greener forms of transportation and energy. Mr. Biden’s bipartisan $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act funded bridge and road improvements as well as providing money for a more resilient electric grid and E.V. charging networks. The vindictive, oil-loving Mr. Trump, who equates green with woke and views climate change as heresy, has worked assiduously to undo it, working to cancel consumer tax incentives and billions in funds for E.V. charging and battery manufacturing projects.

That’s particularly perverse given that Mr. Trump vowed on the campaign trail to make domestic manufacturing a priority. Things haven’t gone as planned. Overall, manufacturing jobs actually declined in 2025, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. His tariffs, which he said would protect American companies, has instead hurt domestic automakers. Even before those tariffs were applied, G.M. had to hand its stake in a Michigan-based battery maker, Ultium Cells, to the South Korean conglomerate LG Energy Solution. That’s significant, because such partnerships are vital to G.M.’s ability to stay ahead in battery technology or expand capacity should demand rise again.

G.M. says it is retaining its current E.V. lineup, but at the same time, it is building more ICE and hybrid models, while foreign competitors remain fully committed to E.V.s. That’s especially true of China, where BYD has become the world’s largest E.V. maker, overtaking Tesla. BYD started as a battery maker and now exports its low-priced E.V.s to more than 70 countries. Eventually, the United States will be one of them. Our ability to compete with BYD and other Chinese competitors is being undermined.

Then there’s the impact downstream. The auto industry’s supply chain is a tiered system of parts and component makers. As part of the write-down, G.M. will take a $4.2 billion hit to cancel orders — and the pain will be felt particularly by small businesses, many of them in red states such as Ohio and Indiana. Some may have to close up shop. And keep in mind that every job in manufacturing typically supports three others.

If G.M. has to spend billions to scale back its E.V. operations, that money will no longer be available to invest in, say, less expensive E.V. models or in new plants. At its current margins in North America, G.M. has to generate more than $16 billion in revenue to produce $1 billion in profit. Paying suppliers not to supply you is hardly a prudent use of capital.

There’s been little pushback from a supine Congress against Mr. Trump’s crusade. Senator Ted Cruz, the Texas Republican, has been openly supportive. Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, a bond trader by profession, doesn’t display much understanding of how commerce works, let alone manufacturing. Energy Secretary Chris Wright seems intent on filling our lungs with even more pollution by keeping coal-fired power plants open. And remarkably, the former first buddy and current Tesla chief executive, Elon Musk, has been equally lame, even as Tesla’s sales are falling. Mr. Musk seems to have already moved on to robots and A.I.

This isn’t the first time E.V.s have lost out to internal combustion engines. When electric vehicles first appeared in the United States in the 19th century, Henry Ford, busy at work on his automobile start-up, even bought one for his wife because of how easy it was to use. No starter to crank. But Ford bet his young company on internal combustion because it was far more practical at a time when vast parts of the country didn’t have access to the electric grid.

A century or so later, his great-grandson, William C. Ford Jr., the company’s current executive chairman, helped move Ford Motor into E.V.s for the benefits that should have accrued to customers, shareholders, the economy and the environment. Instead, Mr. Trump, manufacturing’s King Canute, is trying to hold back the tide of technology, and harming Ford and G.M. (and jobs and our climate) in the process.

Superior technology ultimately wins out. By the time the automobile industry is dominated by E.V.s, G.M. and Ford may have fallen well behind China, thanks to the Trump administration.

This isn’t industrial policy; it’s industrial suicide.

Bill Saporito is a business journalist and a former editor at Fortune and Time.

Source photographs by Joe Raedle, 3alexd, Vladimiroquai and roberthyrons/Getty Images.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post $25 Billion. That’s What Trump Cost Detroit. appeared first on New York Times.