President Trump loves naming things after himself. Here are some federal initiatives and places that have been named (or renamed) for him, or feature his image, in the last year alone:

-

The Donald J. Trump and The John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts

-

A proposed 2026 Semiquincentennial $1 coin

Past presidents have their names attached to federal buildings, naval ships, monuments, libraries, scholarships, White House rooms and currency, among other official federal designations.

But the recent rash of Trump namings, while the president is still in office, makes him very unusual among American presidents, who tend to wait for others to honor them after their presidencies have concluded.

“Throughout Western history, the idea of commemorating and adulating yourself has been considered gauche,” said Jeffrey Engel, a historian at Southern Methodist University.

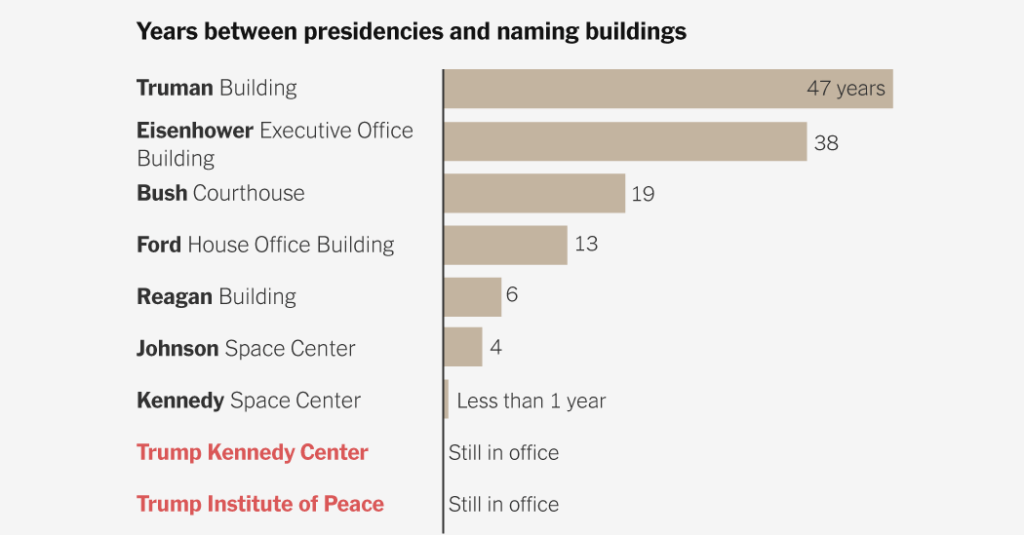

Take the case of government buildings. Several have been named for presidents in recent history, but none had been named after a sitting president. The quickest turnaround was for Kennedy, who was memorialized soon after his assassination. And currently, aside from presidential libraries, no federal buildings have been named or are planned to be named for Richard Nixon, Barack Obama or Joe Biden. Mr. Trump already has two.

Mr. Trump’s enthusiasm for attaching his name to federal architecture may run afoul of more than just custom. The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts was named by an act of Congress, which would seem to complicate the decision by its board to add Mr. Trump’s name. (The center’s spokeswoman said in an email that its new official name was “The Donald J. Trump and The John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts.”) The facade of the United States Institute of Peace also now bears the president’s name, despite continuing litigation asserting the office is not under executive branch control.

Environmental activists are challenging a decision by the Interior Department to put Mr. Trump’s likeness on most annual America the Beautiful Passes for national parks, a possible violation of a law requiring the passes to be illustrated by the winner of an annual park photography contest.

Some institutions, like memorials, are supposed to be named for presidents only after their deaths. The same is true for currency. A 2005 law expanded a series of $1 coins to feature the faces of all deceased presidents, but specifically bars the creation of a coin until at least two years after a president’s death. But a Trump dollar coin was proposed for release later this year. Administration officials have explained that the coin will be made as part of a different numismatic series celebrating the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a set without such an explicit prohibition.

The only other time a living president was on a currency was on the nation’s 150th anniversary in 1926, when a commemorative half dollar coin featured the sitting president, Calvin Coolidge, next to George Washington.

In some cases, Congress has embraced and encouraged the president’s legacy-building enterprise. In their major tax and domestic policy law passed over the summer, Republicans decided to name new savings accounts for babies “Trump Accounts.”

And Mr. Trump says he didn’t ask for his name to be associated with a government website helping consumers buy discounted prescription drugs without using their health insurance. But he seemed pleased to announce that his cabinet officials had named TrumpRx.gov after him anyway.

By numbers alone, Mr. Trump is not an outlier. There are about as many naval ships named for George Washington as all of the places and initiatives named for Mr. Trump combined. But Mr. Trump is the only president to have had a class of warships named after him while in office.

A few projects have been named for sitting presidents before. In 1791, three commissioners appointed by George Washington named the nation’s capital after him while he was president, though Washington still continued to refer to it as the “Federal City.” And during Herbert Hoover’s presidency in the early 20th century, the interior secretary announced that an ambitious dam project would be named Hoover Dam (a decision that was later contested and that wasn’t Hoover’s idea).

For the most part, presidents have been honored by those who come after. In 1990, George H.W. Bush signed a law naming the Interstate Highway System after Dwight D. Eisenhower. President Gerald R. Ford signed a law creating a scholarship named for Harry S. Truman. Richard Nixon named the Roosevelt Room of the White House (a nod to both Theodore and Franklin).

In a statement, Liz Huston, a White House spokeswoman, called the policies named after Mr. Trump “historic initiatives that would not have been possible without President Trump’s bold leadership.”

None of these namings occurred during Mr. Trump’s first term. It’s only a year into his second one, so federal uses of his name and face may continue to accumulate. He has been somewhat cagey about whether a planned White House ballroom might bear his name. And legislation has been introduced to (somehow) add his face to Mount Rushmore.

Margot Sanger-Katz is a reporter covering health care policy and public health for the Upshot section of The Times.

The post All the Things Named for Trump, and How Long Other Presidents Had to Wait appeared first on New York Times.