Originally built to be a drive-through mall in the 1950s, El Helicoide was supposed to be a monument to Caracas’ wealth and modernity. But under the socialist dictatorship, the structure has been the country’s most notorious prison. Human rights groups estimate that Venezuela has the largest number of political prisoners in the Western Hemisphere. Many have been tortured by the state, and women have been raped.

As a gesture of goodwill to the Americans, the regime has released some of its political prisoners in recent days. That’s welcome, but too many remain. Bands of government-backed gangs called colectivos continue to stop people on the streets to check their phones for any evidence they support the United States.

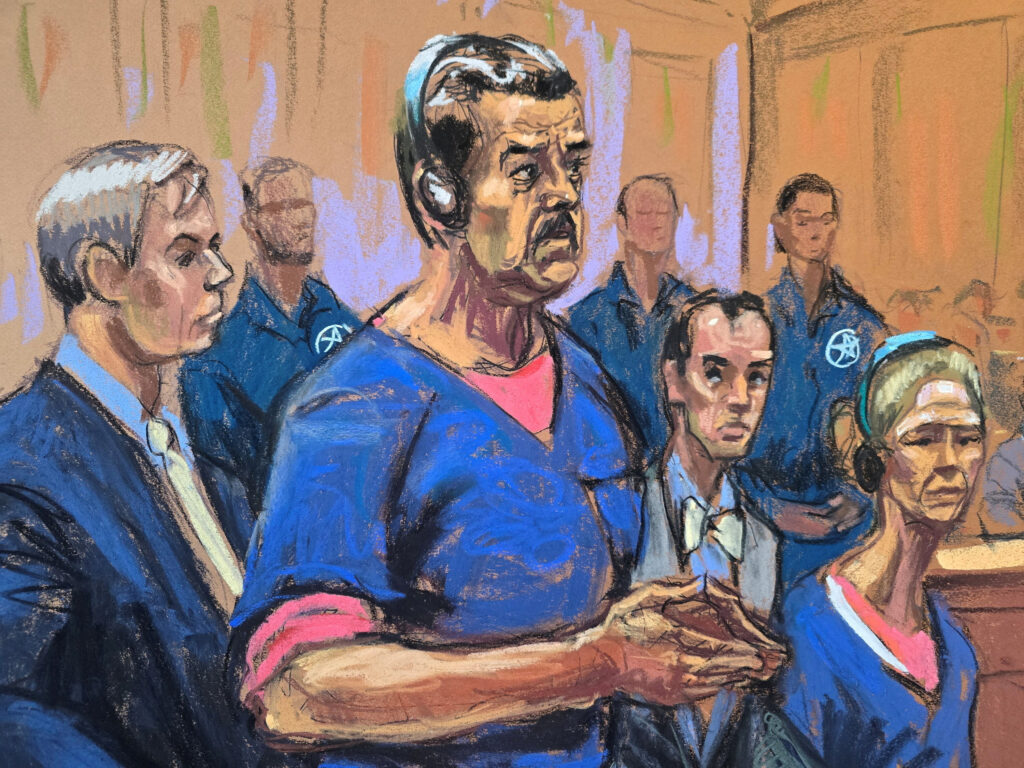

Meanwhile, here at home, the “No Kings” crowd hates heavy-handed presidents, but too many seem oddly tolerant of murderous dictators. Since President Donald Trump’s successful capture of Nicolás Maduro, a disappointing number of Americans have questioned whether the strongman deserves to be jailed.

A reflexive impulse to side with whoever Trump is against should not blind anyone to Maduro’s crimes. This is why the Biden administration placed a $25 million bounty on his head last year.

Like most failed socialist projects, Venezuela started to fail slowly — then all at once. Under Hugo Chávez, high oil prices helped distract from chronic mismanagement of and underinvestment in the nationalized oil industry. He blatantly welcomed American adversaries, including Iran, China and Russia. And he chipped away at constraints on his power. In 2009, the Chavistas won a referendum to abolish term limits, arguing that “Chávez is incapable of doing us harm.”

Four years later, Maduro ascended to the presidency and used those expanded powers to build a monstrous dictatorship and create a humanitarian crisis.

In 2020, the United Nations accused Maduro’s government of committing crimes against humanity. These included extrajudicial executions, politically motivated detention and torture, the erosion of judicial independence and violent crackdowns on protests. Maduro and his cronies fomented lawlessness. The infrastructure of oppression carries on in his absence, as colectivos roam Caracas.

Those spared by Maduro’s cronies were still victims of his disinvestment. Shortly after he took office in 2013, oil prices started plunging and debt triggered hyperinflation. Food shortages became so dire that Venezuelans lost an average of 19 pounds between 2015 and 2016. Maduro repeatedly blocked foreign aid from entering the country.

The gross domestic product contracted about 70 percent between 2014 and 2021, and the vast majorityof the country lives in dire poverty. Eight million Venezuelans have fled since 2014, one of the largest displacements in history. Maduro doctored the results of the last election because he knew he’d lose if he didn’t.

Democrats can criticize Trump for going after Venezuela’s oil and keeping Maduro’s henchmen in place, rather than trying to immediately install opposition leader María Corina Machado. But they cannot deny that a population living on top of the world’s largest proven oil reserves has been starving and suffering for too long.

The post Trump’s Venezuela policy is debatable. Maduro’s evil isn’t. appeared first on Washington Post.