At first, James Watson terrified me. It was 1991 and my first day as the new science writer at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. My boss’s boss was Dr. Watson, the venerable scientist who codiscovered the double helix form of DNA. He greeted me as though he had just remembered that I was supposed to tell him something, “Oh! Nate … ” He looked me in the eye, shook my hand, then stared just over my head, as if checking whether someone more interesting was coming in.

I worked at Cold Spring Harbor for four years. Although I never became close to Dr. Watson, my fear of him abated, mostly. I saw that when he was not performing a public role, he was generally soft-spoken and thoughtful, if stubborn. He had an unnerving habit of answering my questions with a seeming non sequitur. I’d look baffled, he’d fidget and I would at last understand that his response was three steps downfield from where my mind’s eye had been looking.

Near the end of my time at Cold Spring Harbor, I remember seeing Dr. Watson walking around the campus, brandishing a copy of Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein’s new book “The Bell Curve,” which notoriously argued that I.Q. differences between racial groups are genetic. At the time, I don’t recall race having been something Dr. Watson talked about in public (nor had I heard him speak of it in private). That changed drastically after the turn of the century. Jim being Jim, the more the public pressed him not to say those things, the more he said them. It was perverse but predictable. Eventually, his dogged insistence on a connection between race and intelligence cost him his reputation as a scientist and his relationship with his beloved Cold Spring Harbor, one of the great loves of his life.

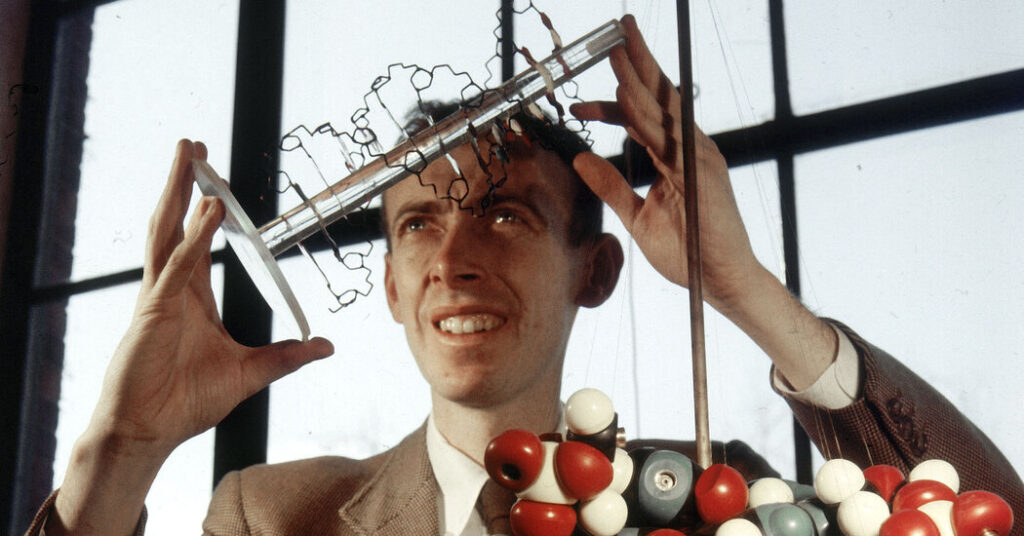

DNA giveth and DNA taketh away. Dr. Watson, who died on Nov. 6, had built his stratospheric career on his total commitment to DNA and molecular biology, which resulted in a Nobel Prize and leadership of the Human Genome Project. DNA made him one of the most significant scientists of the 20th century. But getting carried away with it, insisting against the science and history that it was meaningful to compare I.Q. between races, made him among the most infamous of the 21st.

Genetic determinism is one of those one-single-technofix-will-solve-everything ideas that visionaries can fall prey to, and the history of genetics is lousy with hereditarians promising to end disease, make us smarter and better our society. We’re drawn to magic bullet solutions that cannot solve complex social problems. It is all too easy for someone who makes a genuinely profound discovery to think they have found the secret of life, or the environment, or disease.

Ironically, Dr. Watson’s preoccupation with genetic determinism was far from predetermined. Some of his contemporaries began entertaining eugenics ideas in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and called for deeper studies into claims that I.Q. measured human intelligence and varied across different races. But Dr. Watson stayed out of this eugenics boomlet, even after becoming director of Cold Spring Harbor in 1968.

So what changed? Why did he later become receptive to ideas he had once found repugnant?

Recombinant DNA happened. DNA sequencing happened. The Human Genome Project happened. Like scientists before him, Dr. Watson got carried away by a pretty but simplistic model of the gene that seemed able to explain everything. He had been interested in the gene all his adult life. But by the time he became head of the Human Genome Project, he identified with it. Through the 1980s and ’90s, DNA motifs were incorporated into the fabric of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory — from outdoor sculpture to a 65-foot-tall bell tower.

DNA also became personal. When his older son developed mental illness, Dr. Watson would repeatedly say that he found comfort in the idea that his son merely got a bad roll of the “genetic dice.” Dr. Watson shared this notion with many other families living with genetic illness. On some level, if something is “in your genes,” you’re absolved, it’s not your fault. In this way, genetic determinism is like astrology. Indeed, Dr. Watson himself once said: “We used to think our fate was in our stars. Now we know, in large measure, our fate is in our genes.”

An obsession with the gene, of course, is not a complete explanation for why racist ideas resonated with Dr. Watson — who was bourgeois, Anglophiliac and Eurocentric, proudly elitist and rather fond of the mid-1950s patriarchy. For “The Bell Curve” to strike such a chord, some part of him had to already be receptive to its arguments.

An overweening faith that our genes make us who we are is a terrifying thing. If you think there is one single fundamental essence that makes you you more than anything else, you’re at risk. Though genetic determinism doesn’t necessarily make you a racist, it might move you to support forced sterilization, found a Nobel Prize winner sperm bank, have 17 children or commit other eugenic acts. Exactly what form it takes in any one case depends on culture, family, temperament — even, a little, your genes.

Nathaniel Comfort is a professor of the history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and a fellow of the Center for Science, Technology, Medicine and Society at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of “The Tangled Field,” a biographical study of the geneticist Barbara McClintock, and “The Science of Human Perfection,” a history of eugenics and medical genetics.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post James Watson Saw the True Form of DNA. Then It Blinded Him. appeared first on New York Times.