SAN FRANCISCO — While my colleagues enlisted in the social media wars of the last 15 years, I’ve played the conscientious objector.

Many of them have built big online brands with a schedule of posting, scrolling and engaging, but I’ve done little more than post my columns. No doubt this has been detrimental to my career. But I like to think it has been good for my mental health. So far, I’ve also sat out the artificial intelligence craze for much the same reason: Life is too short to spend most of it online.

So when I heard that a founder of Twitter and a founder of Pinterest were launching a new social networking platform initially dubbed “social media for people who hate social media,” I was intrigued.

When I heard that this platform would harness AI to help us live more meaningful lives, I wanted to know more.

When I heard they had hired the former head of the Unitarian Universalist church in New England to guide product development, I booked a flight to San Francisco to see what it was all about.

Here, in an 1862 home on Officers’ Row at the Presidio, I met the Rev. Sue Phillips, the company’s “founding ancient technologist.” She showed me how she teaches the young engineers and designers to fill their own lives with purpose — in hopes that they will make a product that could potentially inject purpose into hundreds of millions of lives.

The team of designers and engineers from Twitter, Pinterest, Dropbox, Facebook, Google, Medium and elsewhere are now testing software that turns your smartphone into a tool that can answer a question humans since Socrates have been asking: How can we live the good life? They are united by a shared belief that the past actions of Silicon Valley — including some of their own actions — have taken us in a dehumanizing direction.

“We were really ignorant about what could happen,” Christopher “Biz” Stone said of that moment in 2006 when he, Jack Dorsey and two others founded Twitter, now X. “Social media was supposed to make people more friendly, and the true promise of the internet was supposed to be connecting people and making them aware of what each other were up to,” he told me when we met at the Presidio a few weeks ago. Instead, he continued, “it has made them disconnected from their own selves, and now there’s an epidemic of loneliness and anger. It went in the wrong direction.”

Evan Sharp didn’t suffer the same pain of watching his creation become a repository for ugliness; Pinterest, the social network he founded with two others in 2010, fills the more benign niche of helping people share design ideas. But he’s no less distressed. “I feel disappointed by my own lack of care at times, but really at a bigger level the lack of care of the industry,” he told me. “When I look around the Valley, I don’t see anybody taking accountability for what we did with social media,” he added, “let alone what we’re doing with generative AI, which is radically shifting cognitive development without any study.” He asked: “Are we boys playing with toys? Or are we adults who feel responsible for the society that we’re stewarding?”

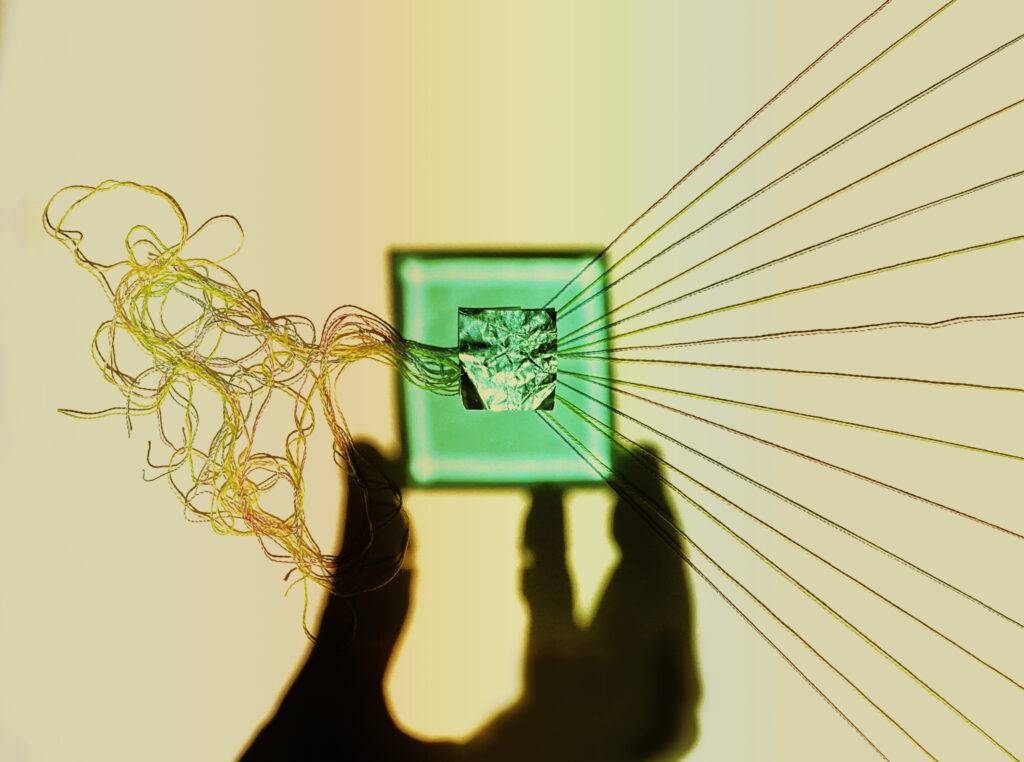

Their bid for redemption is West Co. — the Workshop for Emotional and Spiritual Technology Corporation — and the platform they’re now testing is called Tangle, a “purpose discovery tool” that uses AI to help users define their life purposes, then encourages them to set intentions toward achieving those purposes, reminds them periodically and builds a community of supporters to encourage steps toward meeting those intentions. “A lot of people, myself included, have been on autopilot,” Stone said. “If all goes well, we’ll introduce a lot of people to the concept of turning off autopilot.”

But will all go well? The entrepreneurs have been at it for two years, and they’ve already scrapped three iterations before even testing them. They still don’t have a revenue model. “This is a really hard thing to do,” Stone admitted. “If we were a traditional start-up, we would have probably been folded by now.” But the two men, with a combined net worth of at least hundreds of millions, and possibly billions, had the luxury of self-funding for a year, and now they have $29 million in seed funding led by Spark Capital.

I have no idea whether they will succeed. But as a columnist writing about how to keep our humanity in the 21st century, I believe it’s important to focus on people who are at least trying. Social media, after its promising early days, took a dark turn and is now a deeply alienating force, replacing healthy human interaction and leading us to spend much of our lives looking at our phones. Many fear that AI, still in its adolescence, will take us down the same path because of the financial incentives to maximize eyeballs and time online. But it could go either way, and we as a society still have a choice about how we use these powerful tools.

“We can use them to help increase the amount of meaning in your life and increase the amount of life in your time,” Sharp argued. “I just know we can, because it’s self-evident from what the technology can do. Whether we can do it socially, economically, is a different question.” Quite possibly, West Co. and the various other enterprises trying to nudge technology in a more humane direction will find that it doesn’t work socially or economically — they don’t yet have a viable product, after all — but it would be a noble failure.

To get the latest science on human flourishing and the good life, West Co. consults with its “founding scientific adviser,” Dacher Keltner of the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California at Berkeley and my go-to psychologist on matters of awe, wonder and moral beauty.

And then there is Phillips, who also taught at Harvard Divinity School and who is now designing West Co.’s corporate culture around a series of rituals, which consume about 5 percent of all work hours.

Each morning, staffers light the candle at the “ancestor table,” with photographs of family members dead and alive and other sources of inspiration: Harvey Milk, Jane Goodall, Saint Francis. The founders participate in a fortnightly “covenant” meeting in which they renew their support for each other. Moments of silence precede meetings. Ceremonies mark the changing of seasons. Employees give one another regular updates on their personal triumphs and struggles. Founders rate their weeks on a zero to 100 “poopy to pleasure” index.

Of course, Silicon Valley is full of companies that encourage mindfulness and meditation. Such practices can make employees more relaxed and focused, but they do nothing to change the type of the product these companies produce.

“We are not doing mindfulness here,” Phillips told me. Phillips said her role is to teach her colleagues “what humans have learned about how to live a meaningful life” — which is alien to the move-fast-and-break-things culture of Silicon Valley. Of course, breaking things is sometimes necessary for progress, but “the practices go against a lot of the fundamental strategies of religion and spirituality, which is slow down, take a breath, think about what you’re really doing, ground yourself in what you know and don’t break things, especially when those things are humans.”

Robert Sutton, a Stanford University professor of management science who has worked closely with tech companies, says much of the mindfulness and meditation emphasis of Silicon Valley, and of the many self-help apps it produces, tend toward the narcissistic — “so I can be a more effective capitalist.”

“It sounds to me like what Biz Stone and Evan Sharp are talking about is these are people that have enough [money], and the idea of helping others or doing the greater good is the purpose. The purpose is not just me, me, me, me,” he said. “Unfortunately, I wish they weren’t, but I think they are the exceptions. I actually think the ethos has gotten worse.”

We know from philosophy and from science that the key to human flourishing is to be found in serving a cause greater than self, whether that’s the love of family and friends, a sense of community and belonging, or an appreciation of awe and moral beauty. Of course, if somebody using Tangle decides their highest purpose is in eating ice cream sundaes, the app won’t stop them. But the project revolves around training existing AI models in “what good intentions and helpful purposes look like,” explained Long Cheng, the founding designer.

When you join Tangle, which is invitation only until this spring at the earliest, the AI peruses your calendar, examines your photos, asks you questions and then produces a series of “threads,” or categories that define your life purpose. You’re free to accept, reject or change the suggestions. It then encourages you to make “intentions” toward achieving your threads, and to add “reflections” when you experience something meaningful in your life. Users then receive encouragement from friends, or “supporters.”

A few of the “threads” on Tangle are about personal satisfaction (traveler, connoisseur), but the vast majority involve causes greater than self: family (partner, parent, sibling), community (caregiver, connector, guardian), service (volunteer, advocate, healer) and spirituality (seeker, believer). Even the work-related threads (mentor, leader) suggest a higher purpose.

The search for meaning has led to some substantial changes in the lives of the West Co. workers. Tiffani Jones Brown, the chief operating officer, used Tangle for several months, setting “intentions” — typically three a day — to read poetry, notice nature, do creative projects, cook more or be present for her teenage daughter. (“Savor the unexpected time together. Bring her favorite green grapes.”) “By setting lots of intentions,” she said, “it helped me realize what my soul was actually calling me to do.” And her soul called her to quit her job. She’s now working as an adviser to West Co., so she can spend more with her daughter.

Stone, similarly, came to understand that his life as a serial entrepreneur was causing him to miss his son’s childhood. So, over the past year, he set intentions that every drive to school would be a chance for quality time, and that every time his son wanted to play basketball or ping pong, the answer would be yes. “I feel like my son went from zero to 13 years old in three years, but I felt like he was 13 for three years,” Stone said. “It’s changing my own life.”

There are plenty of apps that scrape your calendar and help you be efficient. There are plenty of other apps that guide you in self-care and resolutions. Tangle proposes to combine centuries of human knowledge about the good life, and extensive knowledge about each user, to build individualized plans for flourishing. “We’re going to figure out how to create a version of their life that’s within reach, that hasn’t happened yet, but that they want,” explained Cheng.

I tried the version of Tangle now undergoing testing. “Why do we exist?” it asked as I began the “onboarding” process. “What matters most? Can software help us show up more fully, more consciously?”

I didn’t use Tangle long enough for the AI to get to “know” me, and my friends and family aren’t on the platform (my wife declined my invitation to join, understandably wary about AI accessing her business calendar) to offer encouragement. Also, I don’t enter much in my own calendar other than reminders and routine appointments — which explains why the AI decided that two of the things that give me purpose in life are replacing HVAC filters and going to the dentist.

Even so, the platform came up with some surprisingly accurate “threads” for me: Land steward. Storyteller. Parent. Partner. I made an “intention” for myself — “I want to reach out and check in with someone I haven’t talked to lately” — and Tangle sent me nudges to fulfill it.

Of course, the platform will change dramatically before the public sees it. But in my three days at West Co., I could see the effects of Phillips’s interventions in the intensely personal nature of the professional interactions. I heard frank talk about sleeping problems, back trouble and burnout, but also about pride from a child’s school parade, an employee’s jazz performance and Phillips’s efforts to become a “lesbian crafter.”

A ceremony to observe Brown’s departure ended with three of the founders in tears. At another meeting, colleagues encouraged Cheng to schedule the hip surgery he’d been postponing; two hours later, it was booked.

Above all, I was struck by the shared purpose expressed by the West Co. workers: a determination to right the wrongs of Silicon Valley. Phillips lamented the “avalanche of really disturbing trends” in tech. Stone described himself and his colleagues as tech industry “misfits.” That’s the same word Larissa May, a West Co. adviser, used to describe the Tangle crew. Her nonprofit, Half the Story, teaches young people about healthy online lives. “I don’t have hope that the industry is going to change,” said May, who puts her hope in “outliers” such as Sharp and Stone.

Ben Finkel, the founding engineer, said he’s hoping for “some kind of reckoning” to reform the industry. “Phones are now like what tobacco was in the 1950s, and we’re just smoking on planes,” he said. “We’re going to look back and be like, ‘I can’t believe we just did that with super-addictive stuff and just put it next to our beds, everyone, all the time.’”

Sharp, who worked at Facebook before Pinterest, blames the smartphone and social media for “a radical colonization of consciousness.” The entire structure of the industry, he said, comes down to this: “We don’t know where we’re going, but we’re going really fast and really hard.”

I, for one, am grateful that some people in tech are at least asking where we’re going.

The post A new approach to living a good life comes from a most unlikely place appeared first on Washington Post.