Growing up near Boston in the 1950s and early 1960s, I picked up the suburban message that the city’s working-class Roxbury neighborhood was for me, as a white kid, a no-go zone. Yet I was in or around the neighborhood a lot because I spent much of my in-town time at the Roxbury-adjacent Museum of Fine Arts.

Most of white Boston never dreamed of Roxbury itself as a source of art, though it was, as a long and sparkling list of contemporary artists who emerged from or touched down in it, attests. As I say, my wonkish teen focus was on the MFA, and specifically on its transcendent collection of Buddhist art, which I loved. And it was a delight to learn, years later, that at least one terrific Roxbury artist — born, in fact, just a few blocks from the museum — had, a few decades before me, been blissing out with the Buddhas too.

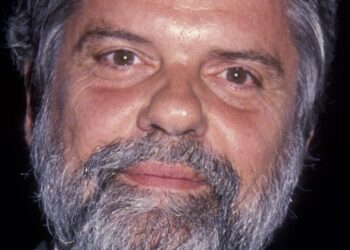

His name was John Wilson (1922-2015). And the first New York survey of his work, “Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson,” which originated at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, is currently gracing the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wilson’s parents immigrated from Guyana to Boston hoping to continue, and perhaps expand on, the middle-class life they had lived at home. They didn’t reckon on the separatist intensity of America’s pigment politics. Wilson’s father, a former white-collar bureaucrat, faced unemployment in Boston. His mother had to support the family through domestic work.

If their financial circumstances were reduced, their cultural priorities remained firm. One of Wilson’s earliest memories was of being held by his father and being read to from books and newspapers. When he demonstrated an early interest in art he was encouraged to pursue it.

In 1939, at 17, he was enrolled, on a partial scholarship, in the nearby School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where he studied for years, producing, almost from the start, astonishingly polished paintings, drawings and prints. In a bust-length old master-style 1943 oil self-portrait that opens the Met’s chronologically arranged show he looks poised and confident. Yet the lithographic prints he was producing the same year were shot through with images of social angst and political turbulence.

In one titled “Breadwinner” a Black man dressed in a business suit and worn-down shoes-— a paternal portrait? — is slouched, as if despondent, on a city park bench. In another, “Adolescence,” a dark-skinned, book-toting youth stands alone in front of a chaotic pileup of figures huddling in what looks like a dead-end tunnel. And in the panoramic, detail-jammed print called “Deliver Us From Evil,” produced in the depths of World War II, images of an African American family flanked by scenes of lynchings and a German Jewish family threatened by Nazi troops mirror each other.

Taken together, the prints and the painted self-portrait, all from the same year, suggest a political and personal perspective that would define Wilson’s career, one famously identified by the historian W.E.B. Du Bois as Black “double consciousness.” It consisted, on the one hand, of a deep sense of pride in Black identity, implicit in the portrait, and on the other a bitter awareness, illustrated in the prints, of the hostility that that identity could evoke in a racist world.

Certainly the Met show — organized by Jennifer Farrell, the museum’s curator of prints and drawings; Patrick Murphy and Edward Saywell of the MFA Boston; and Leslie King Hammond, founding director of the Center for Race and Culture at Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore — gives evidence that Wilson’s confidence in his gifts as an artist were well-founded, and rewarded.

In 1944, when he was still an art student, the Museum of Modern Art acquired the lithograph “Adolescence” for its collection. Teaching gigs, other institutional acquisitions and travel fellowships soon followed.

One took him to Paris for two years, where he tested the waters of modernist abstraction under the guidance of Fernand Léger, and experienced an immersion on African art at the Musée de l’Homme.

In 1950, the year he married, a second grant took him to Mexico. There he stayed for seven years working alongside the country’s leading muralists and printmakers, all declaratively political artists, which he also considered himself to be.

Much of what ‘s in the show from these residences is bland and derivative. But the formal experimenting on Wilson’s part that such work represents paid off in what he went on to do after his return to the U.S., where, following stints in Chicago and New York City, he settled permanently in Boston in 1964 in 1964.1

There, to dramatic effect, he began to fully apply modes of abstraction to his political imagery. And here the work really comes, graphically, to life. Simultaneously, in an era when “advanced” contemporary art had left the figure and narrative content behind, he reaffirmed his devotion to both.

In an interview in the exhibition catalog, Edmund Barry Gaither, founding director of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Roxbury, noted that what was revolutionary about the work of African American figurative artists was the ability of their art “to counter the distorted images of Blacks in advertising media and popular imagery that often denied their humanity.” Taking such control was the baseline impetus for Wilson’s art, and a fuel for the international surge in Black figure painting of recent years.

Then in the early 1970s, Wilson took a big leap in formal direction. He stopped printmaking, long his primary medium. (He would return to it, in a limited way, a few years before his death in 2015.) And he abandoned the cherished idea of doing murals. In 1972 he made studies for a mural to be titled “The Young Americans” consisting of life-size portraits of teenage friends of his children, but didn’t get beyond producing a set of life-size crayon studies, five of which line a corridor outside the show.

And he replaced both of these art forms with another— sculpture, conceived on a monumental scale. One example, a depiction of a father and child sitting together reading, captures a tender personal memory. (A table-top size bronze model for the piece is in the show; the six-foot-tall finished work stands on the campus of Roxbury Community College in Boston.)

Two other sculptures, represented at the Met by sketches and maquettes, are commissioned memorials to Martin Luther King Jr., one in the form of an immense bronze portrait head installed in 1982 in a park dedicated to King in Buffalo, N.Y.; the other a half-length bust, staidly respectful, that has been on view in the U.S. Capitol building rotunda in Washington since 1986.

The most memorable of Wilson’s portrait sculptures, though, which is also the most abstract, seems to have begun as a kind of self-commission spun off from “The Young Americans” project. One of the sitters for the mural, a young African American woman named Roz Springer, also became one of Wilson’s regular models. And drawings of her profile formed the basis for the immense bronze sculptural head, “Eternal Presence,” that now stands on the grounds of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, and, in reduced form, at the entrance to the Met show.

In both versions, it’s materially smooth but culturally textured. A Benin-style version of an MFA Buddha, you might say. It’s indeterminate of gender and race. Its gaze is both inward and outward. It’s an emblem of what Wilson called “a universal humanity,” in which the political angers and longings that storm through his art are resolved. I see all of that. And I see a souvenir of a Boston art connection that a wonderful artist and I, from different neighborhoods of time and space, unknowingly shared.

———-

Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson

Through Feb. 8 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave., (212) 535-7710; metmuseum.org.

Holland Cotter is the co-chief art critic and a senior writer for the Culture section of The Times, where he has been on staff since 1998.

The post John Wilson’s Enduring Art of Racial Politics and Personal Memory appeared first on New York Times.