What is Tucker Carlson trying to do? He is certainly elevating antisemitic ideas on the political right, most recently through his friendly interview with the Hitler-admiring influencer Nick Fuentes that roiled the conservative movement.

But antisemitism is a loaded term with a range of contested meanings in modern American politics. The “alt-right” of the 2010s fixated on Jews as part of its nihilistic and irony-laden online trolling. Some progressives in recent years have fixated on Jews as avatars of oppression.

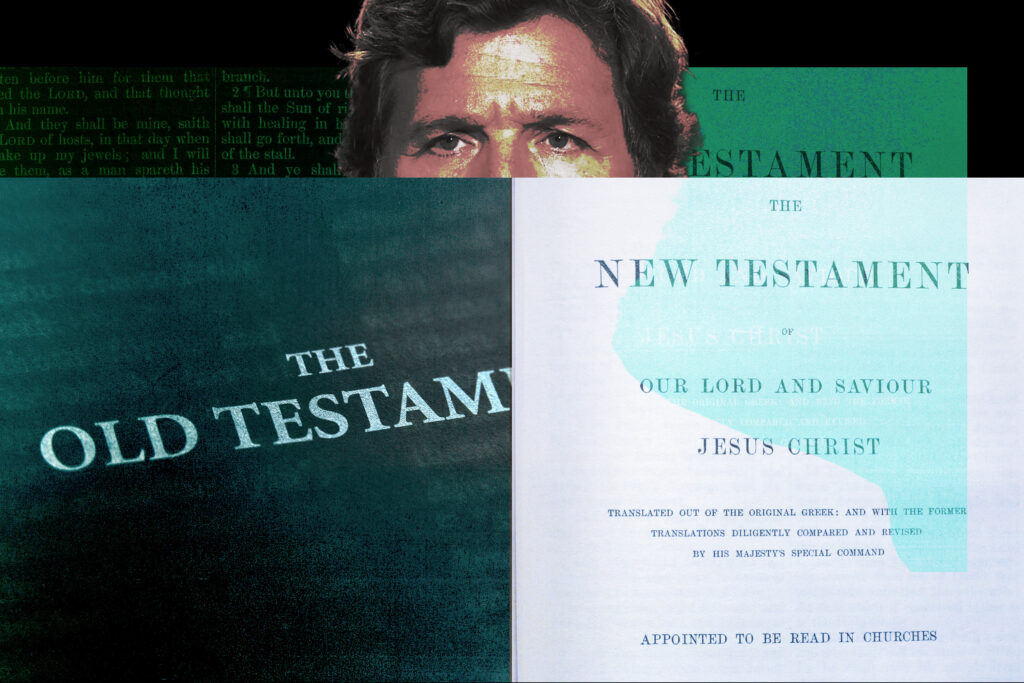

Carlson’s fixation has taken a different and more explicitly religious form. The former Fox News host is targeting a distinctively American, 20th-century concept: The Judeo-Christian consensus. In the landmark 1955 book “Protestant-Catholic-Jew,” the sociologist Will Herberg argued that the three faiths formed the basis of a common civic creed in the United States.

That Jewish-Christian pairing, though not uncontroversial, has proved remarkably resilient over the decades. Carlson sees an opening to undo it. A recent theme of the podcaster is that the Old Testament (the part of the Bible subscribed to by both Jews and Christians) is dark and tribal, while the New Testament (the part subscribed to only by Christians) is the fount of enlightened Western values.

Carlson explained in an August podcast that on a recent reading of the Old Testament, he “was pretty shocked by — as I think many people who read it are — shocked by the violence in it, and shocked by the revenge in it, the genocide in it.” By contrast, he explained this month as the Fuentes controversy raged, “Western civilization is derived from the New Testament.” He added: “The core difference between the West and the rest of the world — not just Israel but every other country — is that we don’t believe in collective punishment because we don’t believe in blood guilt.”

The view that people should be treated as individuals rather than interchangeable members of a collective, Carlson continued, is “a Christian understanding. It does not derive from any other religion.” To hammer the point: “Christianity alone — alone, unique — makes that claim.” Identity politics, therefore, is “anti-Western. It’s evil. And it leads, in the end, inexorably to genocide.”

Carlson is trying to heighten what he sees as contradictions between the Old and New testaments — and by implication between Judaism and Christianity. He’s pushing on an open door: Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts’s video defending Carlson’s Fuentes interview said the think tank would not be “policing the consciences of Christians.” A college student recently asked Vice President JD Vance a question about American support for Israel that included the assertion: “Not only does their religion not agree with ours, but also openly supports the prosecution of ours” (he presumably meant “persecution”).

Making Carlson’s project easier is the fact that the idea of a Judeo-Christian tradition has always been politically charged. Trinity College professor Mark Silk has explained how the concept went through multiple political incarnations in the 20th century.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Silk observes, “Judeo-Christian” entered the American mainstream as a way for Christians to signal their opposition to rising antisemitism, including from sources such as the charismatic radio demagogue Charles Coughlin. During the Cold War, antisemitism in the U.S. declined, but the idea of a Judeo-Christian tradition gained new traction as a stand-in for American values in the ideological struggle against the Soviet Union, which repressed religion. Since the end of the Cold War, the term has been employed by social conservatives to contrast their vision with that of secular liberals.

In other words, the idea of a Jewish-Christian synthesis has been wielded for both progressive and conservative ends in American politics. Carlson’s archenemy, the conservative pundit Mark Levin, recently made a plea for the concept’s continued vitality: “If you reject Judaism and Christianity, and the brotherhood and the sisterhood of the two, not only are you rejecting our Founding, you’re rejecting our country.”

The share of Americans who identify as Christian or Jewish in recent years (around 70 percent) is low compared to the mid-20th century (around 97 percent), both because of the growing number of non-religious Americans and the introduction of other faiths through immigration. The idea of a Judeo-Christian consensus as the key to America’s civil religion in the 21st century might be harder to sustain.

Carlson is a brilliant polarizer. His Fuentes provocation successfully prompted massive recriminations on the institutional right. His gamble is that in the turmoil, he can pry more conservatives away from the Judeo-Christian settlement that arose in the past century and toward his own narrower sect on the right.

I’ve criticized Jewish identity politics. Carlson is exploiting Christian identity politics while casting himself as a champion of the New Testament’s universalism. It’s important to understand his method. But the best answer is probably to ignore him when possible — and when impossible, to highlight the opportunistic cynicism of it all.

The post Tucker Carlson targets the ‘Judeo-Christian’ tradition

appeared first on Washington Post.