MORGANTOWN, Pa. — The Trump administration says it is focused on protecting unaccompanied migrant children. It imposed strict new background checks on those seeking custody of young migrants and cut ties with a chain of youth shelters accused of subjecting children in its care to pervasive sexual abuse.

“This administration is working fearlessly to end the tragedy of human trafficking and other abuses of unaccompanied alien children who enter the country illegally,” said Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who oversees the Office of Refugee Resettlement, or ORR, which cares for unaccompanied migrant children.

But for the past three months, that office has also locked some teenage migrant boys inside a secure juvenile prison in southeast Pennsylvania with a long and publicly documented history of staff physically and sexually abusing juvenile offenders in its care, a Washington Post investigation has found.

ORR awarded $9 million to Abraxas Alliance in August to hold up to 30 young immigrants deemed a danger to themselves or others in its facility in Morgantown. At various times since early October, between five and eight migrant teenage boys have been held inside a dedicated wing of the juvenile detention center, sleeping inside locked cells the size of walk-in closets, according to lawyers who met with them.

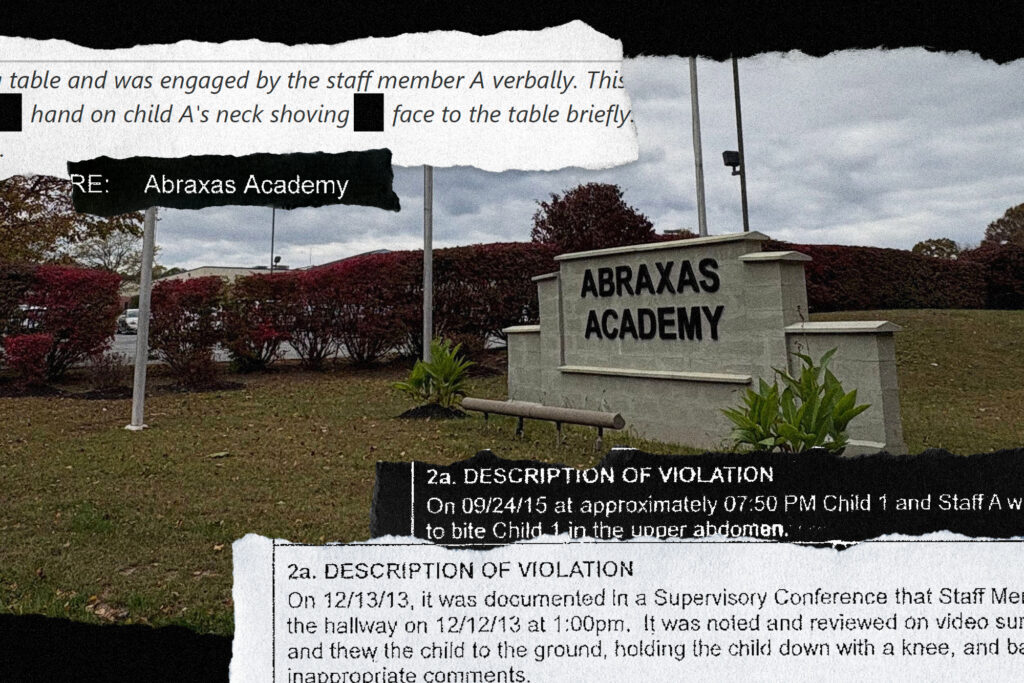

Pennsylvania state inspectors have documented at least 15 incidents since 2013 in which they said staff physically mistreated minors at the Morgantown facility, which holds principally juveniles facing or convicted of criminal offenses. In at least two incidents, officials documented allegations of staff sexually harassing or sexually abusing young residents. The most recent reported abuse occurred in November.

In a lawsuit filed in 2024, six former residents of the facility allege they were sexually abused by staff between 2007 and 2016, accusing management of enabling a “culture of abuse.”

A spokesperson for Abraxas Alliance, the Pittsburgh nonprofit that operates the facility, did not respond to a long list of questions about its treatment of children. After some of the incidents cited by inspectors, Abraxas suspended or fired staff members and submitted correction plans to state regulators, promising to retrain workers on proper restraining techniques and install more surveillance cameras.

ORR has wide latitude over the types of facilities it uses to house children, though federal rules require it to use “the least restrictive setting that is in the best interests of the child.” The rules say ORR may place minors in secure facilities if they have been charged with a crime, or if the agency determines they could harm themselves or others.

HHS spokesman Andrew Nixon said decisions on where to place migrant children “are based on each child’s specific circumstances, behavior-based risk assessments, and legal criteria.” All the teens at the Morgantown facility were provided a notice with “specific details as to why they are placed there,” he added.

Some of the migrant boys have no pending criminal charges, and several have parents or close relatives in the U.S. asking to be reunited with them, said Becky Wolozin, a senior attorney at National Youth Law Center who visited the facility and spoke to some of the boys in November.

The Post was unable to identify any of the boys or verify Wolozin’s claims about their circumstances, because neither their immigration lawyers nor government officials would share details about their cases due to strict rules protecting the records of minors.

License revoked

In November, Pennsylvania revoked one of the three licenses held by different units within the Morgantown facility, Abraxas Academy. The state accused Abraxas of “gross incompetence, negligence, and misconduct” following a Nov. 4 incident of staff violence against a child, state records show. According to those documents, a staff member put his hand on a child’s neck and shoved his face into a table, an incident the facility’s operator did not report to local authorities.

Ali Fogarty, a spokeswoman for Pennsylvania’s Department of Human Services, said state law prevented her from commenting on the incident, including whether the child was a migrant placed by ORR or another juvenile held in the facility. The state increased its monitoring of the Morgantown facility and reduced its maximum capacity under one license by 25 residents while the company appeals the revocation. Its two other licenses were unaffected, and it is still permitted to hold more than 100 individuals, Fogarty said.

Nixon, the HHS spokesman, said ORR “will make any necessary adjustments to its use of the facility based on the outcome of the state’s licensing process” and its own review of the incident, adding that “ORR has zero tolerance for sexual abuse and harassment of children in our care.”

The problems at the nation’s only secure jail for migrant youths are unfolding as the Trump administration pushes a series of measures it says are aimed at safeguarding the 2,300 unaccompanied migrant children in its custody, as well as those it releases to sponsors within the country.

In March, ORR ended its use of shelters operated by Southwest Keys — a Texas nonprofit which the Justice Department sued in 2024, alleging its workers repeatedly sexually abused children in the nonprofit’s shelters from 2015 to at least 2023. The company said in a 2024 statement that the lawsuit did not “present the accurate picture of the care and commitment our employees provide to the youth and children.” The department dropped the lawsuit last year.

Around the same time, ORR also began requiring people to provide income documents and submit to DNA testing, fingerprinting and interviews before regaining custody of young migrants, including their own children, which agency officials say will help ensure they are not being claimed by traffickers.

The Trump administration says President Joe Biden had released tens of thousands migrant children to sponsors with little or no vetting, including to some adults with a history of violent crimes. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement says it’s enlisting the help of local law enforcement agencies to locate the children and verify their safety.

Jen Smyers, a former deputy director of ORR under Biden, said this population has faced abuse for decades, across several administrations. She said stricter vetting cannot always prevent mistreatment.

Partly as a result of the Trump administration’s new vetting procedures, the average child remains in ORR custody about six months — nearly three times longer than at the beginning of 2025, government data shows.

A history of abuse allegations

By jailing migrant children in a secure detention center, especially one with a recent history of abuse, the administration is exposing these young people to some of the same risks it says it wants to eliminate, said Jonathan White, a former career HHS official who managed the unaccompanied children program during part of Trump’s first term.

Under any previous administration, a track record of physical or sexual abuse would be “instantly disqualifying” for federal contracts involving the care of minors, White said. “This is the kind of thing under Republican and Democratic administrations you terminate existing grants for — you don’t give new grants to places like that.”

Abraxas Academy, part of a chain of 10 youth detention and treatment centers, holds dozens of teenage boys from surrounding areas, many of whom are serving sentences for violent crimes or awaiting court hearings. Rob Monzon, a former director of the Morgantown facility, calls it “the most extreme setting in juvenile detention.” Its young inmates, some who claim to be from gangs, frequently lash out at one another, vandalize the building and attack staff members, he said.

State inspection records show that staff members have at times responded with violence.

One staff member “picked up [a child] by the shirt and threw the child to the ground, holding the child down with a knee, and banging the child into the wall,” a 2013 report on the state’s website said. Another threw punches at a different minor and yet another bit an incarcerated child in the abdomen, other reports said. The reports noted that one staff member “frequently escalates situations” by applying restraint holds that are “known to cause pain to the child.”

Workers have been trained to defend themselves by placing inmates into restrictive holds, waiting for them to calm down and calling for help from other employees, according to Shamon Tooles, who worked as a supervisor at Abraxas Academy for eight months in 2023. But due to a lack of training, supervision and frequent short-staffing, he said, some workers resorted to fighting back.

“A lot of the staff were just scared,” said Tooles, who said he does not condone any mistreatment of children.

In December 2016, Pennsylvania state inspectors said they found “a preponderance of evidence” that a staff member sexually harassed a child at the Morgantown facility. The staff member, who was not identified, was put on leave and subsequently resigned.

One of the former detainees who is suing Abraxas Alliance claimed a staff member took away his food or gym privileges or locked him in his room if he did not comply with sexual requests.

In court records, attorneys for Abraxas Alliance denied any wrongdoing and said they would need the names of all the abusers to confirm details of the alleged abuse. The lawsuit, which covers allegations lodged by 40 former residents from five Abraxas facilities, is still active and no trial date has been set.

Nixon, the HHS spokesman, said Abraxas Academy was the only state-licensed facility that submitted a bid on the ORR contract that “operated a secure care facility for youth between the ages of 13 to 17.” He said the contract is part of an effort to “restore” the government’s capacity to hold “children whose needs cannot be safely supported” in less restrictive settings.

Fresh paint

Abraxas Academy sits at the end of a three-mile road, deep in the farmlands of Amish country. It’s so remote that when nine boys escaped through a hole in the barbed wire fence in 2023, they were quickly discovered a few miles away, lost and shivering in the rain, ready to go back, according to Paul Stolz, the police chief of nearby Caernarvon Township.

When Wolozin visited Nov. 5, she said the walls smelled like fresh paint and workers were still renovating the floors of the wing designated for immigrant boys, separate from the teens serving criminal sentences. At that time, there were eight migrant boys; at least two have since been transferred to less restrictive facilities, and another was moved to an adult detention center upon turning 18, according to their lawyers. At least two new detainees arrived in December.

Wolozin’s group, which has supported Democratic politicians and causes, advocates for children in the foster care, juvenile detention and immigration detention systems and has special permission to meet with them per the terms of a landmark 1997 legal agreement.

According to Wolozin, the conditions for migrant boys at Abraxas Academy mirror those of children serving criminal sentences. The boys are woken from their cells and counted every morning. Their use of a “family room,” with TVs, board games and bean bag chairs, is restricted to certain times, as is their access to an outdoor recreation area with farm animals and an indoor gym. Some have told lawyers and advocates they have been limited to two 15-minute phone calls to family members per week. Federal rules require at least three calls per week.

Wolozin, who interviewed five of the migrant boys but has not reviewed their files, said one appeared to have severe cognitive disabilities. Another had completed his sentence for a criminal charge and was set to be released to his family but was instead transferred to ORR custody. Others had never been in jail before.

“What became very apparent to me is that ORR is sending children to a juvenile detention center who should not be there,” she said.

The vast majority of the migrant children in government custody live in shelters where they move freely around a campus. But the government can place children in more restrictive settings if they are deemed a risk— a broad authority that former child welfare officials say ORR has misused.

In 2018, ORR found it had “inappropriately placed” 18 of the 32 minors who were in secure facilities at the time, according to the court deposition of a former agency official. One child, the official said, had been placed in a jail because they were an “annoyance” and not an actual danger.

ORR had moved away from juvenile detention centers since 2023, after the government settled a series of lawsuits that claimed children in these facilities were subjected to inhumane punishments or illegally locked up based on being mislabeled gang members. As part of the settlements, ORR agreed to implement new rules providing stronger legal protections for migrant children in custody.

Now, the administration is expanding the practice of secure detention once more. Along with the 30 beds for migrant teens at Abraxas Academy, ORR is exploring a second secure facility that would hold up to 30 additional migrant children in Texas, government procurement records show.

Advocates for migrant youths say these jails are unnecessary and harmful — and evident from the government’s tumultuous history with ORR detention centers before the Abraxas contract.

‘I just went on myself’

Young people detained at Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley Juvenile Center said in 2018 court declarations that they had been locked in small rooms for most of the day. Some said they were beaten by guards. If they acted out, some said, they were put in a restraint chair, with straps around their head, elbows, legs and feet, and wheeled into a room where they were left to sit alone for hours with their head covered in a white mesh hood so they couldn’t spit on the guards.

“This is embarrassing, but on one occasion, I had to pee, and they wouldn’t let me, so I just went on myself,” a child identified as “R.B.” said in a court filing. “I know one or two other kids this happened to as well; they peed on themselves while they were in the chair.”

Shenandoah’s operators said their use of the restraint chair was not abuse. ORR policies permit such restrains as a last resort. A federal judge ruled in 2018 that the government had improperly placed minors in secure facilities including Shenandoah but did not determine whether its use of restraints constituted abuse.

California’s Yolo County Juvenile Detention Center commonly used chemical agents and physical force to control children, the state’s attorney general found in 2019. A spokeswoman for Yolo County said in an emailed statement that the facility took measures to reduce its reliance on chemical agents, including staff training on nonviolent crisis intervention.

Community activists pressured city and state officials to stop jailing migrant children there, citing lawsuits and the growing costs of defending against them. One Salvadoran teen alleged in court papers he was shipped across the country to the facility simply because New York police claimed he was a member of MS13. A federal judge found no unequivocal evidence of the boy’s ties to any gang.

By 2023, Shenandoah, Yolo and another juvenile detention center in Alexandria, Virginia, had all opted not to renew their contracts with ORR.

“Nobody wants these contracts,” said Holly S. Cooper, co-director of the Immigration Law Clinic at UC Davis, who was involved in the effort to end the Yolo contract. “There was a massive public outcry.”

According to Smyers, ORR’s No. 2 official at the time, the agency in late 2023 solicited proposals for a new kind of facility where children could have restrictions increased or reduced depending on their behavior. ORR has not awarded this contract, but Nixon said it is still a priority.

Fights, an escape attempt

The Abraxas chain of youth detention and treatment centers has changed ownership at least twice. At the time of many of the abuse incidents in the inspection reports, it was owned by private prison firm Geo Group, which purchased the chain for $385 million in 2010. Geo has said in court records it is not aware of any sexual abuse.

The company sold parts of the Abraxas business to a nonprofit group run by Jon Swatsburg, the unit’s longtime executive, for $10 million in 2021. At the time, Geo was losing federal contracts and being shunned by major banks in response to community activism against its business. Geo still owns the building in Morgantown and leases it out to Abraxas Alliance, securities filings show.

A spokesman for Geo did not respond to requests for comment.

Swatsburg, who has overseen the properties for more than two decades, was paid $752,000 by Abraxas and related entities in 2022, according to the most recent tax filings available. Inperium, an investor in the nonprofit group, announced Swatsburg was departing in 2023, but he continued to list himself as president and chairman of Abraxas in corporate filings in 2024 and 2025. As of last year, Swatsburg was also listed as a vice president of Geo Group.

Last year alone, police responded to at least 34 incidents at the facility, local records show, including inmate fights, at least one attempted escape, a suicidal detainee, an incident that left three police officers with minor injuries and another incident in which a staff member’s finger was partly amputated by a door.

Meanwhile, the migrant boys at Abraxis have told advocates that they feel stuck.

“They had plans and family, and lives and school and girlfriends, and things going on that they planned to do,” Wolozin said. “Instead, they are in this place.”

Aaron Schaffer, Jessica Contrera, Daniel Gilbert and Maria Sacchetti contributed to this report.

The post Trump administration jails migrant teens in facility known for child abuse appeared first on Washington Post.