A supply shortage is the last thing tech companies want to talk about at CES. The annual trade show is their chance to promote new products and drum up excitement for what’s coming, not discuss the one thing that could make selling new products in 2026 an uphill battle.

But I’ve read the reports. I’ve seen the RAM kits selling for thousands of dollars. I’ve heard the statements from laptop suppliers and part manufacturers warning investors about what’s coming. You probably have too. The memory chip shortage is already dire for companies and for individuals who build their own PCs. But don’t think because you only use a laptop and a phone you’re going to get out of this so easy.

While the situation remains grim, I met two companies who have engineered ways out. Their plans aren’t guaranteed to work, and they won’t be easy to pull off. But they just might be our only hope.

Waiting for the Bubble to Pop

“We’re waiting for the AI bubble to pop,” a spokesperson from a small PC manufacturer who wished to remain anonymous told me when asked about how they were handling the memory shortage.

None of the big laptop manufacturers or PC builders would say something quite that direct, but actions speak louder than words. While happily selling “AI PCs,” Lenovo, Dell, Asus, and HP have all stated that they’ll be doing everything in their power to secure their supply of DRAM for the foreseeable future.

“I’ve been at this a long time. This is the worst shortage I’ve ever seen.”

Dell COO Jeff Clarke

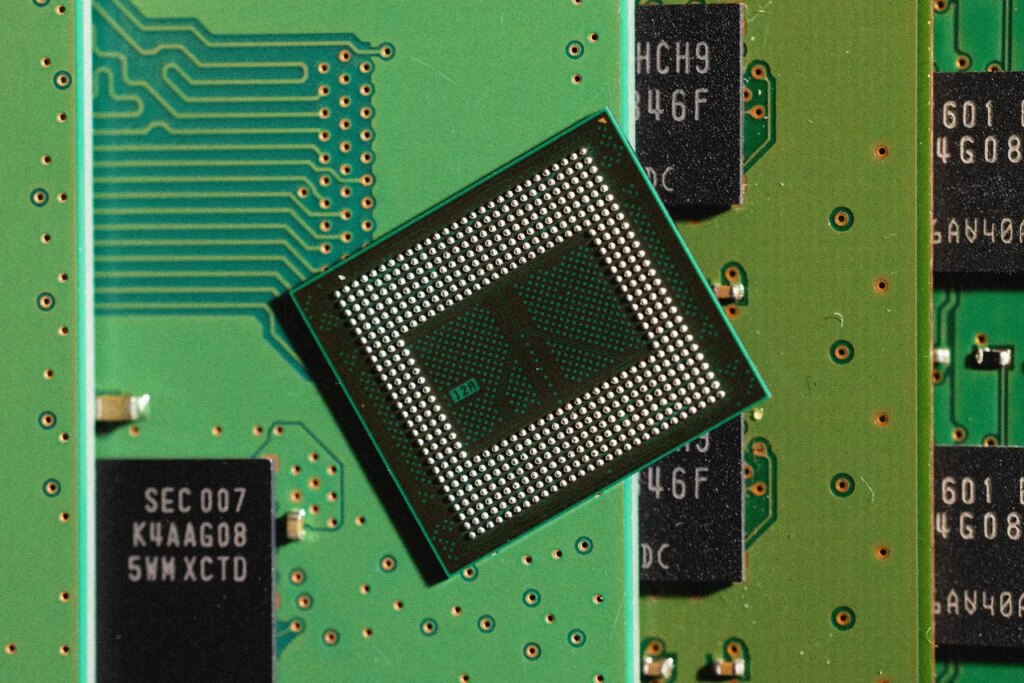

DRAM, or dynamic random-access memory, is the kind of memory used in laptops and phones, and it’s what the three main memory manufacturers are now turning their backs on in favor of high-bandwidth memory for AI data centers. Lack of memory is the main reason you can’t run ChatGPT on your PC and have to outsource every prompt to the cloud.

I spoke to Dell COO Jeff Clarke in December about what his company was doing to remedy the situation. “Our focus has been to secure the supply. That has always been the number one rule of our supply chain—to never run out of parts. We’ve been at this for a while. This just didn’t show up. So we’ve been out there for a while securing our supply.”

It’s a sentiment similar to what competitors like HP and Asus have told shareholders. But hoarding memory will only have two effects: It will raise prices even more or further tighten supply. Rumors of higher prices on electronics have begun to flood the internet. On the last day of 2025, Asus went first, officially announcing that it would be raising prices and tweaking configuration options on existing products. This was the follow-up to a leaked internal document from Dell stating that prices could rise by as much as 30 percent in 2026.

When I asked him how bad things really were, Clarke looked at me with a sigh. “Look, I’ve been at this a long time. This is the worst shortage I’ve ever seen. Demand is way ahead of supply. And it’s driven by AI. It’s driven by infrastructure. You’ve seen the spot market price—it’s up to five times from September. That will manifest. It already has in contract pricing.”

While the average person can buy straight from a retailer, laptop manufacturers have to negotiate contracts on DRAM. According to an analyst from Citrini Research, prices on DRAM increased by around 40 percent in the final quarter of 2025. It’s not slowing down; it’s escalating. Prices will be up to 60 percent higher in the first quarter of this year. From everyone I talked to this week, I got the impression that the memory shortage would last not months but years.

So, if waiting this one out isn’t the solution, what is? As it turns out, there are some very clever people in the world with some incredible ideas, all based around reducing our dependency on AI in the cloud.

The Real AI PC

You may not have heard of Phison, but the multibillion-dollar Taiwanese company has been building critical controllers for NAND flash memory chips for decades and even claims to be the inventor of the original removable USB flash drive. The founder and CEO of the company, Pua Khein-Seng, has been outspoken for months about warning about the coming memory shortage.

Pua explained to me that the current storage shortage isn’t necessarily about revenue. It’s about storytelling. “Every CEO, every company—they want to increase valuation,” he says. “Stock price is storytelling. Memory companies need a story.”

From his perspective, that’s how we ended up where we are. But at CES, Pua didn’t just bring more concern and warnings. He brought a solution. The product is called aiDAPTIV, an add-in SSD cache for laptops that can “expand” the memory bandwidth of your PC’s GPU. Flash memory, such as what’s found in an SSD, is typically used for long-term storage, leaving the DRAM for the fast, temporary storage that your system needs to function. AiDAPTIV, which is built using a specialized SSD design and an “advanced NAND correction algorithm” can, Phison claims, effectively expand the available memory bandwidth for AI tasks, which are currently bottlenecked.

What does all that have to do with solving the memory shortage issue? Well, while enabling more AI is what aiDAPTIV was originally developed for, Pua also positioned it as a solution to the DRAM shortage. As he explained, manufacturers could lower the DRAM capacity of laptops, going from 32 GB to 16, without reducing the PC’s capabilities. That sounds like a great deal, especially since it’s what Dell, HP, and Lenovo were planning to do anyway.

One of the great advantages of aiDAPTIV is that it doesn’t require any internal changes to the existing hardware. It just slots into an open PCIe slot. MSI and Intel have announced early support, and theoretically, things could begin to shift rather quickly. We might all have to accept laptops with less DRAM, but if Phison’s claims are true, that might not matter in practice as much as we used to think.

The Hail Mary

I also spoke to Carl Schlachte, the CEO of a company called Ventiva, which has invented a novel thermal approach that replaced laptop fans with a specialized iconic cooling engine. No fans, just a solid-state thermal solution that ionizes air to create a silent way of moving air. That’s fascinating on its own, but again, there’s a way this new technology also addresses the long-term problem of the memory shortage. Once you remove fans from a system, it opens up lots of extra space for other things, such as extra memory.

“The holy trinity of memory is capacity, bandwidth, and topology,” Schlachte says. Topology is the distance the RAM modules are from the CPU. While this isn’t a huge concern in data centers, it’s a severe limitation when it comes to the allocated space for more memory on laptops. By designing a smaller motherboard, freed from the clutter of cooling fans, more physical space for DRAM suddenly becomes possible. Schlachte believes this is the piece of the puzzle that memory manufacturers are missing.

“High-bandwidth memory is solving for bandwidth in the data center in a space where the need is so great that they’ll pay anything,” he says. “Not sure that makes a lot of economic sense for the long haul.”

As Schlachte explains, making memory for AI data centers isn’t actually cost effective; it’s far more difficult to manufacture compared to DRAM. Given the proper incentives and signals from the market, there’s no reason memory makers wouldn’t return to pumping out DRAM again.

Training foundational AI models will always need the cloud, but if AI PCs could handle the vast majority of how people use AI today, specifically with running large language models, it’ll make less and less sense for memory manufacturers to be solely focused on the data center. In other words, if you build it, they will come. That’s both Phison’s and Ventiva’s theory, at least.

This whole rescue plan hinges on building enough demand on the PC side for on-device AI processing—enough demand that it makes an impact on the bottom line for memory makers. And to do that, individuals and corporations need to be persuaded not only to fully embrace AI but also to want to do their computations on-device. Schlachte pointed to Goldman-Sachs and similar institutions that buy laptops and require private, secure AI that doesn’t send sensitive data to the cloud.

By putting more AI performance in the hands of PC buyers, the hope is to wean us off our reliance on the cloud. But these players won’t be able to turn this ship on their own. They’ll need to convince laptop manufacturers, who need to talk to Intel and AMD, who then all need to tell a concerted, unified story to memory manufacturers. It’s a big lift. But if all these companies want to avoid ta serious drop in PC sales as a result of increased prices, it’s an effort that needs to happen.

I ended my interview with Schlachte by asking him what he thought might happen if none of these ideas go as planned and we decide to just wait it out—beyond just having to pay more for worse laptops.

“We blow our inheritance money on the data center,” he said. “And in order to pay for it, we enshittify the whole thing. We take this opportunity to literally lift people up, and we turn it into another vehicle for advertising. It stays in the data center, because a limited number of companies control your access to and from it. They’re going to rent this back to you. I’m passionate about this, because think I could actually have a hand in switching the powers back to you and I, the human beings.”

The post The Daring Attempt to End the Memory Shortage Crisis appeared first on Wired.