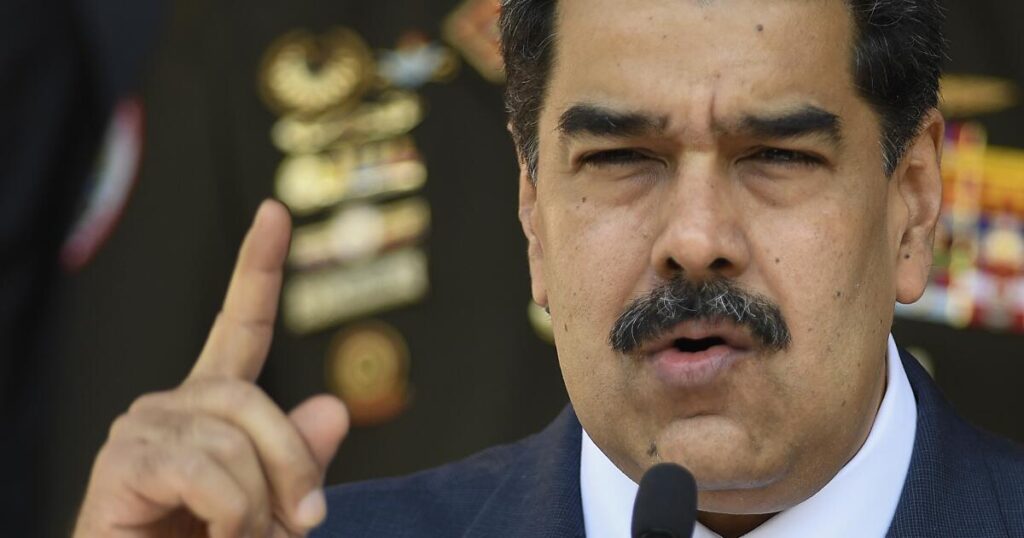

(Bloomberg) — Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro looks to be heading to trial in an American court after his capture in a US military operation that leaves open the future direction and leadership of his oil-rich nation.

The Venezuelan leader’s spiriting away into US custody along with his wife marks the dramatic downfall of an autocratic ruler who clung to power through an economic collapse and humanitarian crisis that prompted millions to flee the country.

Surviving international isolation, US sanctions, attempted uprisings and even an alleged drone assassination plot, Maduro held the presidency since 2013, most recently claiming he won a third six-year term in 2024 following elections widely dismissed as fraudulent.

In 2020, under President Donald Trump, the US charged Maduro and more than a dozen of his associates with drug trafficking and offered a $25 million reward for information leading to Maduro’s arrest. In 2025, after Trump returned to office, the bounty on Maduro’s head was doubled and US warships were sent near Venezuelan waters under the banner of a regional anti-narcotics campaign, prompting Maduro to accuse the US of “fabricating” a war against him.

That conflict has now resulted in the Venezuelan leader’s seizure, raising questions not just over his own fate but over what comes next for a nation that has endured so much. Maduro, 63, will stand trial in the US on criminal charges, Senator Mike Lee said in a post on X early Saturday after a phone call with Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

Questions will inevitably now be asked of Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last year for her pro-democracy efforts. She left her hiding place in Venezuela to travel to Oslo to receive the award and subsequently left Norway in mid-December for an unknown destination. She has said she intends to return to Venezuela.

Machado and her team had been working on a transition plan for the first 100 hours and days after Maduro’s departure from power.

Handpicked successor

As the handpicked successor of Hugo Chávez, the revolutionary leader who transformed Venezuela into a showcase for socialism, the less-charismatic Maduro won a disputed election by a narrow margin in 2013. Clinging to power became his priority after oil prices crashed in 2014 and Venezuela’s petrostate economy unraveled. Amid the wreckage, Maduro concentrated control in the hands of loyalists and the military, creating parallel institutions to neuter the opposition-led Congress.

Maduro “may be hated by most of society and disliked by many of his associates,” wrote Javier Corrales, a professor of political science at Amherst College and author of a book on Venezuela’s path to authoritarianism. “But he has proved a canny architect of his regime — one in which the only people who can truly tear down the system are the ones with the most to lose from its demise.”

Almost 19,000 people have been detained for opposing Maduro’s government since 2014, though many were released, according to Caracas-based human-rights group Foro Penal. The United Nations human refugee agency says almost 8 million people have left Venezuela in pursuit of better lives. That has in turn proven to be a political flashpoint in Latin American countries including Chile.

A 2019 UN report cited “documented cases of extrajudicial executions by security forces” and accused the Maduro regime of instilling fear in its population to retain power; Venezuela’s government called that report “a selective and an openly biased vision” of human rights in the country.

Loyal to Chávez

A former bus driver and union organizer for Caracas’s metro system, Maduro built his rise on loyalty — first to the working class, then to Chávez, his political mentor. Maduro cast himself as a humble revolutionary shaped by his years in the streets and his early trips to Cuba, where he received political training in the 1980s. He served as foreign minister for more than six years and briefly as vice president before Chávez’s death.

Chávez handpicked Maduro as his successor in December 2012 before departing to Cuba for what would be his final round of cancer treatment. “My firm, complete, absolute opinion,” Chávez said on television, “is that if something happens to me, you elect Nicolás Maduro as president.”

After Chávez died months later, Maduro declared himself his son, promised to remain “loyal beyond death” and claimed Chávez had blessed his presidential campaign through a bird that whistled to him while he prayed.

For all his swagger, Maduro never had Chávez’s magnetism. Over time, he found comfort in eccentricity — singing salsa at rallies; dancing on stage with his wife, Cilia; mispronouncing English, French or Latin words; and reminiscing about his youth as a long-haired rocker.

He sometimes joked about being called a dictator, saying he resembled Stalin “because I’m big and have a thick black mustache.”

Union Roots

Nicolás Maduro Moros was born on Nov. 23, 1962, in Caracas. His father, Nicolás Maduro García was a prominent trade union leader. His mother was the former Teresa de Jesús Moros.

He was president of the student union at José Ávalos high school in El Valle, a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of Caracas. As a bus driver, he organized a union with his father. He also became active in the MBR-200, the civilian wing of Chávez’s military movement, while Chávez was in prison for a failed 1992 coup attempt.

Cilia Flores, who headed the legal team that won Chávez his freedom in 1994, would become Maduro’s wife in 2013. From a previous marriage, Maduro had a son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, known as Nicolasito.

Maduro won election in 1999 to the National Constituent Assembly, the body convened to draft a new constitution. A year later he was elected to the National Assembly, where he rose to speaker.

In 2006, Chávez named Maduro minister of foreign affairs, a post from which he amplified Chávez’s incendiary rhetoric. At a regional summit in 2007 he called Condoleezza Rice, then the US secretary of state, a hypocrite and compared US treatment of suspected terrorists to acts committed under Adolf Hitler. Rice had criticized the Chávez government for closing down a private TV station.

The ailing Chávez named Maduro vice president in October 2012, setting the stage for him to rise to the presidency.

Nightly Protests

At first, Maduro tried to imitate Chávez — the booming baritone, the fiery anti-imperialist speeches, even the catchphrases. But Venezuela wasn’t the same country. Months before revenue from oil sales plummeted in 2014, there were nightly demonstrations in Caracas to protest shortages of basic goods, the world’s fastest inflation and rising crime.

The following year, the opposition trounced Maduro’s party in congressional elections — its biggest victory in decades. Maduro responded by tightening his grip on the courts and electoral council, blocking a recall referendum in 2016 and organizing votes that excluded or outlawed his rivals.

Hyperinflation devoured salaries, hospitals ran out of medicine, and millions of Venezuelans fled on foot across the border. The once-mighty state oil company, PDVSA, crumbled under corruption and neglect. In 2017, more street protests were met with tear gas, rubber bullets and gunfire. About 165 people were killed. Reports of human rights violations of detainees in protests poured in international organizations.

Emboldened, Maduro ran for a second term and claimed victory after a 2018 vote dismissed as a sham by the US and other governments. Shortly after, and amid growing discontent, he survived a drone attack allegedly meant to assassinate him.

Venezuela’s opposition-dominated National Assembly declared his rule illegitimate in 2019, prompting the US, the European Union and more than 50 other countries to recognize the legislature’s president, Juan Guaido, as Venezuela’s legitimate temporary leader. Adding to the pressure, the US sanctioned the country’s oil industry, its central bank and Maduro’s closest officials. But the military remained behind Maduro, who successfully waited out Guaido’s challenge.

Rival Parliaments

In 2020, when a new legislature was due to be elected, Maduro’s loyal Supreme Court packed the electoral council, prompting the opposition to boycott. The US and EU refused to recognize the results, which handed him full control of the National Assembly — where his wife and son held seats. The opposition countered by extending its own mandate beyond its constitutional term, leaving Venezuela with two rival parliaments and a deepening stalemate that paralyzed the nation’s politics.

Negotiations mediated by the international community to eventually solve the political crisis ran afoul after Maduro’s democratic missteps.

After a small opening by the US under President Joe Biden conditioned on the holding of fair elections, Maduro was granted a respite from some oil sanctions. In July 2024, however, he ran for a third term while banning Venezuela’s main opposition figure, María Corina Machado, from the ballot, and permitting little foreign electoral monitoring. A government-backed electoral council declared him the winner without showing proof.

Venezuela’s opposition presented overwhelming evidence that Machado’s stand-in candidate, Edmundo González, had won by a landslide. Maduro’s refusal to release the vote tallies and subsequent crackdown on dissent led to widespread condemnation.

Maduro liked to present himself as a survivor, the last guardian of the Bolivarian Revolution. But for millions of Venezuelans, he came to symbolize something else entirely: the slow, grinding collapse of a dream that once promised to lift them out of poverty.

The post Maduro approaches his last act as Venezuela’s autocratic leader appeared first on Los Angeles Times.