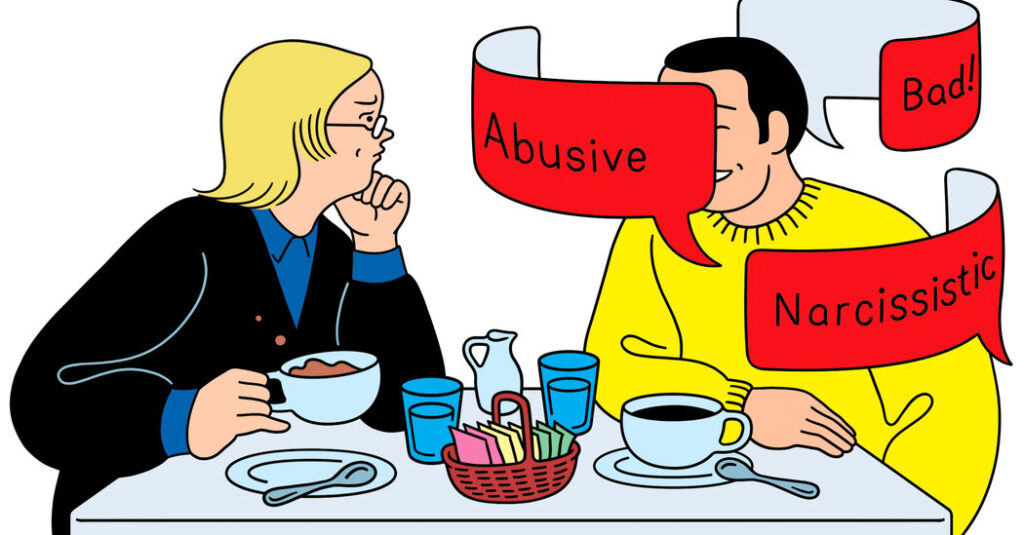

I recently discovered an app where women anonymously discuss men to warn one another about predators and abusers. While the intent is noble (and extremely important), anonymity allows anyone to say anything, potentially harming undeserving men who can’t defend themselves.

Scrolling through, I encountered a discussion about a male friend of mine. A woman describing herself as his ex accused him of abuse and narcissism. When I asked for more information, she refused to share details, becoming defensive and claiming he would retaliate. Eventually, she told me an inconsistent story. That said, I know how common inconsistencies are when it comes to trauma.

I always err on the side of believing women (what would any of us gain from making false reports?), and I know that abusers can seem like “nice guys.” I would feel terrible dismissing a woman’s story of abuse, but I am conflicted about ending friendships based on an anonymous app. Normally I would listen to my gut, but even my gut is stumped. Despite my fondness for my friend, I’ve known him for less than a year, and the fact that he treats me well does not guarantee that he is a good person. I have been ignoring my friend’s texts, but I really do miss him and don’t know if writing him off is the right thing to do. So how would you navigate this situation, and what are the broader ethical implications of this app? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

Your quandary reflects the pros and cons of these anonymous venues. There’s a reason they exist; men have long mistreated women with impunity. When people have shown themselves capable of causing serious harm, sharing that information with those who might be vulnerable to similar treatment serves a protective function.

But the same feature that makes contributors feel safe, anonymity, is also one that invites abuse. If you share a concern with people you know, they have some context for evaluating your claims. And because you have a relationship with them, you will pay a social price if they decide that you are untrustworthy. So you have some incentive to take care. If you write something anonymously on a website for strangers, however, neither of these conditions hold.

That doesn’t mean that anonymous warnings are usually mistaken or that people who report abuse are generally unreliable. A difficulty is that even a sincere account can be hard for an outsider to evaluate, especially when it consists mainly of diagnostic labels rather than descriptions of events. You’re deprived of the specifics you would normally use to calibrate someone’s judgment. Reasonable people may be in accord about what happened but not about what it meant; you might not agree with someone about whether she had been subjected to emotional abuse even if you had witnessed the interaction. At the very least, you’re already in a position to form some independent judgment about your friend’s character, including whether traits you would associate with narcissism have shown up in your dealings with him.

None of this means the woman wasn’t genuinely mistreated. But there’s a world of difference between being willing to listen seriously to a stranger’s accusation against a friend and accepting it as a definitive verdict, especially when the story shifts and she declines to respond to your requests for further information. (Inconsistencies are common in all memory retrieval, but the research literature does not support the claim that trauma makes memories more inconsistent.)

You shouldn’t betray her confidence. You haven’t concluded that she has abused the system, she has voiced concern about retaliation and she no doubt had a bad experience with your friend. That means you have to decide what to do without taking up these allegations with him. You’ll inevitably be on the lookout for evidence that your doubts about her testimony were mistaken. But you shouldn’t feel that you have to give up on a friend on the basis of the evidence you now have. If he’s really the man she describes, there’s a good chance that he will eventually show you; until then, you’re free to treat him as the man you know.

A Bonus Question

Several months ago, I withdrew my support for my estranged husband’s green-card application. Our marriage had ended in emotional abuse and financial manipulation, and I felt I could no longer, in good conscience, act as his sponsor. Recently, I learned that an administrative error by his attorney reopened the case, and I am now being urged by his friends (one of whom raised the specter of Anne Frank!) and even the lawyer to resubmit the support forms. They argue that if I don’t, he’ll be forced to return to Russia, where the political conditions are dire.

I sympathize with that reality, but I also feel deeply uneasy: He has been reckless, deceptive and financially irresponsible, and I no longer trust him. Agreeing to support him would mean assuming legal and financial liability for years, effectively tethering myself again to someone who has mistreated me.

Because of all this, I’m torn. Do I have a moral obligation to help him stay in the United States, despite the personal cost and my lack of trust? Or is it ethically permissible to refuse? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

Although the absence of your support doesn’t mean your estranged husband will be unable to secure a green card (other routes include the asylum process and employer-based options), it will plainly worsen his odds. This would be a bad outcome for him, but it wouldn’t be simply your doing. His misbehavior is what led to your estrangement and to your current hesitations. You have direct experience with his conduct and his financial recklessness, and you can’t be required to discount it, especially when the monetary and legal exposure would fall squarely on you.

In principle, his friends could sign an indemnification agreement to reimburse you for any liability; I notice this doesn’t seem to be on offer. Instead, they are reproaching you — and invoking Anne Frank — for failing to put your money and peace of mind at stake, without volunteering to incur any risk themselves. The basic issue, though, involves a failure of reciprocity. You are not obliged to formalize a trusting relationship of support with a man who has proved himself unworthy of such trust or to entangle yourself with someone you’re entitled to leave behind.

Readers Respond

The previous question was from a reader who wondered whether it was ethical to lie to animal shelters in order to help their senior mother adopt a dog. They wrote:

My mother is in her late 80s and lives alone in a house with a big fenced yard. She’s sharp, mobile and surrounded by friends. She has always lived with a dog, and she gave her last one a wonderful life until his recent death. She’s ready to welcome another older companion who fits her lifestyle. When she recently tried to adopt, though, several rescues refused because of her age. A few of her younger friends — myself included — have offered to act as a front and adopt on her behalf. She sees this as unethical. If a dog were to outlive her, I’d gladly take him or her in. And I can’t help thinking that the companionship, exercise and purpose a dog provides far outweigh the small deceit it might take to bring one into her home. Which is the more ethical course: honoring the system’s ageist rules, or bending those rules in service of compassion? — Name Withheld

In his response, the Ethicist noted:

Given the shortage of homes for pets in shelters, a blanket ban on adoptions by older people seems bonkers. … Part of what’s wrong with ageism is that it involves treating individuals according to group stereotypes. I’m inclined to think that there’s a decent case for doing what you propose: It would benefit the dog, your mother and maybe you. But there’s an even better case for telling shelters that you’d be the designated backup adopter were your mother to become unable to care for the dog; if desired, you can sign a document to this effect. Many shelters accommodate these plans (in some cases as part of a “seniors for seniors” program, involving older pets); it lets them check a box and lets an older person get a rescue. As your mother probably told you at some point, lying, even for a good cause, is best avoided.

(Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

As a volunteer for a foster-based rescue, I’m very saddened to learn that most rescues will not adopt to this octogenarian. As the Ethicist points out, there is an overabundance of animals waiting for loving homes, and anyone interested should be considered. The rescue I’m with asks on the adoption form what plans are in place to care for the animal if the adopter should experience a life change or death. Many applicants say that it’s provided for in their will or that they have a large support system of animal lovers who would step in. Other times, they admit this question has prompted them to think about it for the first time. Just assuming an elderly person cannot care for a dog or cat is wrong, plain and simple. A five-minute phone call to the vet who cared for this woman’s previous pet would shed light on the sort of care her past pets received. — Jamie

⬥

While I agree with the Ethicist’s suggestion, I take issue with labeling the rescue’s policy as ageist. I have volunteered at my city’s animal shelter for the past 18 years, and I cannot tell you how many times we have taken in pets whose owners have died or gone into care. These pets are very often geriatric themselves and in need of medical care because the frail owner had been unable to adequately care for them. There is not a large market for elderly companion animals, and it is heartbreaking to know these pets will likely spend their golden years in an institution rather than a home. Perhaps a hard and fast policy that restricts adoption to elderly patrons without consideration for individual circumstances is overly rigid, but I suspect it comes more from a place of compassion, not ageism. — Carla

⬥

I lost my senior dog last summer, and I knew that I wanted to get another dog soon. I had heard about people in my age group being turned away by rescues, and feared I’d have to go to a breeder. Instead, I applied at several rescues with my daughter as a co-adopter even though she doesn’t live with me, with the idea that she would take responsibility for the dog should I no longer be able to care for it. We were honest about this, and were approved at every rescue we applied at. Three months ago, we adopted a new dog, no lying or obfuscation necessary. And even though my daughter doesn’t live with me, she helps with the dog, takes her to the dog park often and even participates in her training. — Susan

⬥

I am a veterinarian who owned a practice in a blue-collar community for 40 years and am now a relief vet in a retirement-oriented community. The level of commitment, care and resources available to my older clients for their pets often surpasses that which was available to the broader community I served for so many years. Studies have clearly shown the benefits of pet ownership for seniors. In my opinion, denying them these relationships borders on elder abuse. The perfect solution, to my mind, is the one the Ethicist suggested: adoption with a backup plan. Shelters are run with good hearts but often little common sense. — Eileen

⬥

I volunteer at my local humane society. We do not refuse adoptions to older folks, but private shelters may have very different rules. It is my belief that shelters have a legitimate right not to adopt some animals out to older adopters. Someone who is 80 years old, no matter how much they seem to have defied biology, should not have a young animal underfoot. One good fall can really change how old a person feels. And I have seen too many animals returned to the shelter when their owner either dies or moves into housing that will not allow the animal. Meanwhile, the letter writer and their friends, no matter how willing they may be right now to take the dog in, have no idea what their living situation may be if the dog suddenly finds itself homeless. And it is, in fact, unethical to lie and to make promises you very well may not be able to keep. If the woman wants a pet, she could try fostering or adopting a senior animal. As a society, we age-gate a lot of things. Sometimes it is the right thing to do. (And I’m saying this as a 65 year old.) — Crystal

The post Someone Made Anonymous Accusations About My Friend. What Should I Do? appeared first on New York Times.