When Charlotte LaRoy was in elementary school, she had a quiet revelation.

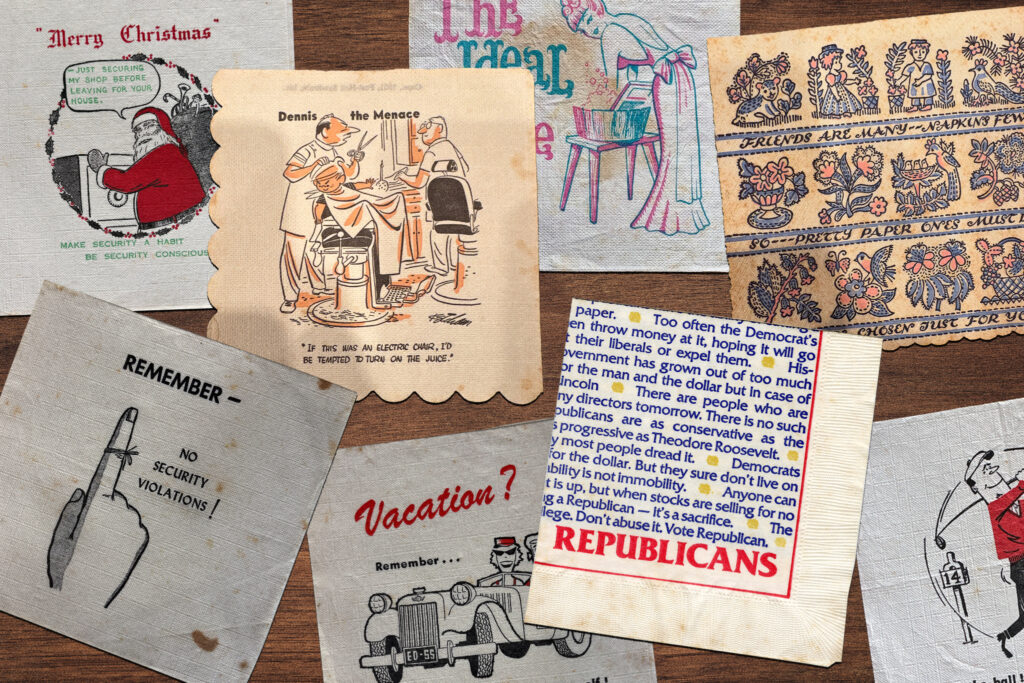

Paper napkins are beautiful.

It was the 1940s, she was the daughter of a federal food-safety scientist, and she was just discovering the spectacular variety of face-and-finger wipes.

She noticed their size, shape, color, design, texture — and “ability to do the business that they do, which is blow your nose, pick up something you spilled on the floor,” LaRoy said.

That early fascination seeded what over decades would become a paper napkin collection worth preserving. LaRoy kept sliding new finds into a blanket box under her bed — until, some years ago, she finally walked into the Library of Virginia. LaRoy handed them over, more than 1,100 in all, surprising and delighting curators. They are now being preserved in perpetuity alongside documents from the Founding Fathers and tomes dating to the 15th century.

LaRoy built a collection that is head-shaking in its scope, from the elegant to the everyday, offering an intimate view into the life of one woman and a remarkable window into decades of American history and social change.

There’s a cartoonish and menacing series of espionage warnings on napkins from the Pentagon. Some date back to the 1950s Red Scare era. “Keep classified information to yourself, pardner!” reads one with a stubbly-faced cowboy.

By nature of the medium, there’s also an outsize trove from bars, many of which embody the ribald humor and casual sexism of their time. One features a bare-backed woman at a washboard and the words “The Ideal Wife.”

There are jolly Christmas scenes, advertisements for extinct airlines and country music lyrics. There is a fan-shaped one, rectangular ones and some that unfold to a bigger canvas.

Intricate “Map-kins” unfurl to reveal road trip destinations, like an eccentric gold miner’s castle in Death Valley and Duckwater Peak in Nevada: “Quack! Quack!”

A few offer snapshots of political moments, with one from civil rights advocate A. Linwood Holton Jr.’s inauguration as Virginia’s governor in 1970 and another from a celebration of L. Douglas Wilder’s ascent as the first African American elected a U.S. governor two decades later.

In 1984, the year Ronald Reagan would go on to crush Walter Mondale in the presidential election, a pair of dueling red-and-blue-printed napkins — packed with aphorisms and digs — sought to boil down the philosophies of the two major political parties.

“Republicans study the financial pages of the newspaper. Democrats put them on the bottom of the bird cage,” reads a snippet from one.

“For a working man or woman to vote Republican this year is the same as a chicken voting for Colonel Sanders,” snaps the other.

When LaRoy contacted Dale Neighbors, the visual studies collection coordinator at the Library of Virginia, about her collection in 2017, he wondered: Who on earth would save such a stockpile?

“I don’t know what to do with them anymore,” he recalled her saying.

Then LaRoy brought them in.

Neighbors knows the power of what curators call “ephemera,” which one expert, Maurice Rickards, defined as the “minor transient documents of everyday life.” That can be everything from tea bag tags and fruit crate labels to report cards and razor blade wrappers. When he was a curator at the New York Historical Society, Neighbors used ephemera to help director Martin Scorsese’s production team make sets for the films “The Age of Innocence” and “Gangs of New York” appear as authentic as possible.

He views the distinctive mid-century designs on LaRoy’s napkins and the series from the Pentagon as among the items likely to capture the interest of future researchers. He was moved by her reaction when he accepted them.

“You know, it was important to her, and just to see somebody else cares can be really rewarding,” Neighbors said.

Years after handing them over, LaRoy responded to a phone call about her awesomely quirky collection with a joyous laugh.

She didn’t know quite what to expect when she gave them all away, but talking about them publicly hadn’t been part of the plan for the former D.C. law firm clerk with an artistic eye but low-key demeanor. She had nurtured other creative hobbies as well, such as weaving old computer cords and phone parts into colorful sculptures she called “Miscommunication Baskets.”

Over the years, she rarely pulled out the epic napkin collection to show it off.

“I really didn’t talk about it very much, unless I had to say, ‘Well, I’d like a napkin,’” LaRoy said, still chuckling, at 83, about the absurdity of her claim to disposable fame.

Often, she’d just quietly slip one in her pocket. One rule: They had to be unused. She shied from the plain and tried to minimize repeats. “You don’t need napkins each time you go to the same restaurant, you know?” Some were picked up by people who worked with LaRoy’s parents, who would occasionally bring them home for her, she said.

Her father was a Food and Drug Administration official who would become a leading expert on preventing pesticide contamination in the food supply, and the family moved from California to Northern Virginia when she was a girl so he could take a job at headquarters. He built a collection of music from the Pacific Islands, which he eventually donated to preservationists in Hawaii.

Her mother was an analyst at the Pentagon, and LaRoy also worked there some summers and for a later stint.

Their cross-country drives in the family’s Hudson were a good source for napkin discoveries, as were the places she went for birthdays, weddings and other milestones. They provided a patchwork family diary.

“Some of them I could look at and remember where it was and re-enjoy the things that we did in those places,” LaRoy said.

She often struggles with her memory now. She said her father had Alzheimer’s late in life.

At their home outside Richmond in December, LaRoy and her husband, Bernard, whom she got to know hiking at Roosevelt Island in the Potomac River, sat in the late-afternoon light at their dining room table. She looked through dozens of snapshots, captured earlier that day, from the Charlotte LaRoy Paper Napkin Collection, the formal title given to her once-informal project. It was the first time she’d seen them in years.

She giggled at one golf-themed Pentagon warning — “Stay on the ball! Security is YOUR job!” — and at a pink-printed cocktail napkin featuring a curvaceous model hemmed in by leering men in dapper suits. “Girls with curves are usually surrounded by men with angles,” it reads.

“Not sure they can do that anymore,” Bernard said. His wife built the collection for herself, not for the recognition, something Bernard said reflects who she is.

As she looked through them, she was struck by some of the beautiful ones — like one with a heart and two birds — but she wasn’t remembering many of the names, places and meaningful moments behind them.

Then she stopped at a wedding napkin with shiny blue, intertwined hearts.

In embossed script, it read:

Stacey & Andrew

November 6, 2010

“Yeah,” she said, her voice trembling with recognition. “That’s our son.”

The post A Virginia woman’s epic paper napkin collection is being preserved appeared first on Washington Post.