For decades, Jeff Galloway’s heart was at growing risk of giving out, but neither he nor his doctors knew it.

A former Olympic distance runner, Mr. Galloway seemed to be a model of good health. He ate meticulously and logged about a marathon a month from his 60s into his mid-70s. In the early 1980s, he pioneered the run-walk-run method, which, by giving people permission to walk regularly, allowed more people to become consistent runners. It has since become known as the Galloway method, and in some parts of the world, Jeffing.

He went on to promote the benefits of moderation in dozens of books, arguing with relentless optimism that, with proper conditioning and strategic walk breaks, anyone can run a marathon. For half a century, he was a fixture at road races around the world, smiling and mellow.

But in the spring of 2021, after a workout on a rowing machine, Mr. Galloway was overcome with dizziness and fatigue. It was the onset of a heart attack, which progressed to heart failure. During another episode a week later, which occurred in a hospital, his heart stopped pumping altogether for four and a half minutes. It took two different defibrillators to bring him back to life.

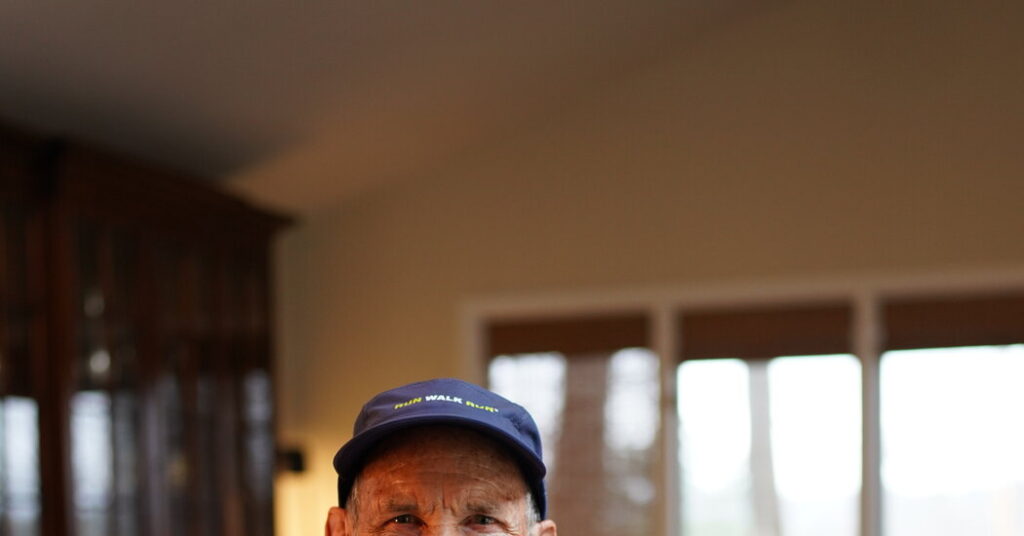

“If I had been anywhere else, I would not be here today,” Mr. Galloway, 80, told me. We sat in his suburban Atlanta home, just a few feet from where he had needed to drape himself over a chair to avoid collapsing after the rowing incident.

One possible cause, he and his doctors came to believe, was Agent Orange, the herbicide used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, which the Department of Veterans Affairs has since linked to coronary artery disease. Mr. Galloway served in combat as a Navy lieutenant and was exposed to the defoliant through drinking water.

He had no family history of heart disease but had developed a complete blockage of one of his coronary arteries, which researchers have observed in other veterans exposed to the toxin. The blockage likely began to form decades ago, his doctors told him, growing and increasing his risk with each passing year. It took five stents to save his life.

As we sat at his dining room table in early December, Mr. Galloway was dressed for a run, in black jogging pants and a hat advertising his coaching program. He moves more slowly than before the heart attacks, and he’s only able to jog for a few seconds at a time before taking a walk break. But his desire to cover long distances hasn’t waned.

Since early last year, he has set his sights on returning to marathoning.

When we met, he had recently walked 21 miles and was feeling good. He was hoping to run-walk the Honolulu Marathon a few weeks later, but he tripped and broke his kneecap a few days before the race and had to push back those plans.

He projected an upbeat attitude for the thousands of fans who had been cheering on his expected comeback — including the more than 100 who’d flown out to Honolulu to run with him — telling them he’d be back out there soon.

He needed to hear this perhaps more than anyone. Privately, he was devastated. “I was ready to do it, and it was pulled away,” he said. He had come so close, he said, only to have the finish line move further out of reach.

But he is determined to cross a marathon finish line this year. “I’ve had a lot of goals that were like burning embers in my motivation,” he said. “Doing another marathon, to me, feels like the strongest goal I’ve ever had in my life.”

If he achieves it, Mr. Galloway could become the first person to have completed the distance in eight consecutive decades of life. He isn’t motivated by records anymore, though. At age 80, running another marathon is, at the most fundamental level, about returning to the version of himself that he loves most: the athlete who endures.

In many ways, Mr. Galloway’s quest represents the ultimate test of his promise that anyone can run a marathon.

A human metronome

When Mr. Galloway first became a champion of walk breaks, he was among the fastest runners in the country.

Mr. Galloway ran track at Wesleyan University in the mid-1960s, but he didn’t rise to a world-class level until after he finished two tours in the Navy. In 1972, at age 27, he earned a spot on the track and field team that would compete in the Summer Olympics in Munich, coached by the Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman. With his long hair and ’70s mustache, Mr. Galloway was often mistaken for the runner Steve Prefontaine, who was a close friend.

Even then, Mr. Galloway was a master at pacing himself, like a human metronome, his longtime running friends told me. He’d hold back early in a race, then pass most of the field at the end.

“He was a fierce competitor,” said Bill Rodgers, a multi-time winner of both the Boston Marathon and the New York City Marathon and one of Mr. Galloway’s teammates at Wesleyan. But Mr. Galloway’s secret weapon was patience, Mr. Rodgers said.

Historians credit the 1972 Olympics with kick-starting the running boom in this country, after an American, Frank Shorter, won gold in the marathon event. But while Mr. Shorter made distance running aspirational, Mr. Galloway helped make it accessible.

Before the term “runner’s high” had entered the lexicon, Mr. Galloway had discovered that running long distances improved his state of mind and gave him a sense of purpose. He also found that the glory he felt as an elite athlete, doing something other people couldn’t do, wasn’t as meaningful to him as sharing the mental benefits of running with others — and showing them that running was something they could do, too.

In 1973, he opened one of the country’s first specialty running stores, Phidippides, in part to serve as a hub for runners who wanted to meet and talk shop. Along with his wife, Barbara, he would go on to open around 60 of these stores. He also hosted running clinics for beginners around the world, convincing skeptics that road racing wasn’t just for those who were trying to win, but for everyone.

By the end of the decade, with less time to seriously train, he worried about getting injured on his long runs. So he started taking short walk breaks every mile or so. During the 1980 Houston marathon, at age 35, he decided to walk through every water station, and he was delighted to finish the race faster than any marathon he’d run continuously, with a time of 2:16:35.

Mr. Galloway began evangelizing about the run-walk-run method at clinics, and found that the promise of walk breaks motivated would-be runners. The method caught on, and he churned out guide after guide to overcoming the mental and physical challenges of running long distances.

American sports culture doesn’t often reward slow and steady. But for Mr. Galloway, the point of run-walking has always been to be able to keep run-walking. As he advanced through his fifties and sixties, he moved from the front to the middle of the pack. Most of his former teammates stopped running marathons altogether.

Learning to walk again

While recovering from his heart failure, Mr. Galloway learned that his decades of training likely helped to save his life. Not only did his consistent run-walking slow the progression of the blockage, but it also helped him to develop what doctors call collateral circulation: His heart grew new blood vessels, which kept him alive when the original vessels became fully blocked.

For nearly a month after his heart stopped, Mr. Galloway was confined to a hospital bed. At first, an alarm would sound any time he tried to get up and move. “The closest I’ve come to depression has been that period of not knowing whether I would be able to exercise again,” he said.

After a few weeks, his doctors cleared him to start walking, but he struggled to keep his balance, having seemingly lost all coordination. So he tried to follow his own advice — the guidance he had given thousands of aspiring runners, to take it slow, be patient and meet himself where he was.

He went for longer walks on the streets around his home. Finally, after two months, he felt ready to try jogging, with his doctor’s blessing.

Mr. Galloway often told beginners to start by running for 10 seconds, but he felt dizzy after only three. His cardiologist warned that pushing through the dizziness would get him into trouble. So he didn’t.

Gradually, over many months and in consultation with his doctors, he worked up to running 10 seconds at a time, interspersed with walk breaks. He relied on his mantra of many years to carry him through: relax, power, glide.

Around this time, Amby Burfoot, a former editor of Runner’s World Magazine and another teammate of Mr. Galloway at Wesleyan, told him that he’d done some research and learned that Mr. Galloway had a chance of becoming the first person to complete a marathon in eight consecutive decades.

(Mr. Burfoot, who is 13 months younger than Mr. Galloway and one of only a handful of elite runners from the 1960s and 1970s still running marathons today, is also a contender, depending on how 2026 shakes out for both men.)

The prospect of another marathon invigorated him.

The persistence high

After we spoke at his home in December, Mr. Galloway and I drove a few minutes to the start of a soft dirt path that ran through the woods, alongside the Chattahoochee River. He had trained for countless marathons on this path since the 1970s. (He has run 236 in all.)

After about a mile of walking together, he felt ready to try running. He suggested jogging slowly for 10 seconds and walking for 30, then repeating. He warned me that he might not make it the full 10 seconds. But after a few warm-up intervals, he glided forward with seemingly little effort.

For now, he’s signed up to run the Honolulu Marathon at the end of the year, the same race he had planned to run before his knee injury, since Honolulu holds special significance for him. In 1974, he won the race. The following year, he proposed to his wife after crossing the finish line. Of the hundreds of marathons he’s run, it’s held in one of the most beautiful settings, he said.

But perhaps most importantly, the course has no time limit.

When he won the race, he ran at a pace of about five and a half minutes per mile. This year, he will be aiming for 17 minutes per mile at best.

Since his knee injury, he’s had to use a walker to get around, and he is cleareyed that he will face obstacles in the months ahead.

“It’s a mountain that I’ll be climbing,” he said. “I’m going to get much more fatigued than I have been in 10 or more years. I’m older now, so it’s going to really be harder for me to deal with a lot of these things. And I know that there are going to be issues that come up after age 80 that did not come up when I was younger.”

“All of these things keep circling, like a cloud,” he added.

But he said he’s found confidence in knowing that, throughout his athletic career, he’s come back from injuries and illnesses, including getting hit by a car in college and coming down with pneumonia before the 1976 Olympic trials. In 2012, he fractured his hip. Eighteen months later, he qualified for the Boston Marathon.

“I had these deep-seated doubts that I was very, very concerned about, and almost gave up in a number of those instances,” he said. “And on every single one of them, I worked my way out of it, one piece at a time.”

When we spoke a few weeks after his knee injury, he was celebrating the fact that he could put weight on his knee again, for short periods of time. He knows he’ll need to go “baby step by baby step,” he said. Once he’s able to walk comfortably again, he said, he plans to increase his step count in gradual increments, until he reaches 26.2 miles.

“My mission now, at the age of 80-plus, is to show that people can do things that are normally not done, and can do them safely,” he said.

In darker moments, he’s asked himself if it’s worth it to put his body through the rigors of training, to strive for a goal that would be challenging for anyone. But then he reminds himself that if he’s learned anything from the past few years, it’s that there are no guarantees with his health or life, and so, why not? The meaning he gets from trying outweighs the risks, he said. He can slow down and keep going at the same time.

Mr. Galloway has considered that Honolulu may be his last marathon. (“If it goes well, I will leave the door open,” he said.) He’s also made peace with the possibility that he may have to sit and rest along the course, or may not finish at all. If that happens, he said, he’ll most likely try for another.

The day we ran together along the river, we discussed some recent triumphs among his coaching clients, most of whom are over 60. He also asked about the last marathon I ran, and commiserated when I told him that I hit a wall at mile 20. And he told me that, when training feels particularly hard, he likes to channel ancient hunter-gatherers, who had to run for survival. His mood was jubilant.

The distance flew by, one 10-second jog at a time. “This really is what I need today,” Mr. Galloway said. “It feels absolutely super.”

The post 50 Years Ago, He Was an Olympian. At 80, He’s Just as Happy to Finish Last. appeared first on New York Times.