In 2025, protest policing in major US cities increasingly took on the character of a spectacle: overwhelming deployments, theatrical staging, and aggressive crowd-control tactics that emphasized signaling power over maintaining public safety. This was not a one-off episode; it followed the deployment of federal troops into multiple Democratic-led cities, prompting lawsuits and court challenges that local leaders described, with justification, as militarized intimidation.

expired: police cooperating with protesterstired:police using controversial crowd-control tacticswired: police confronting protesters for content

Read more Expired/Tired/WIRED 2025 stories here.

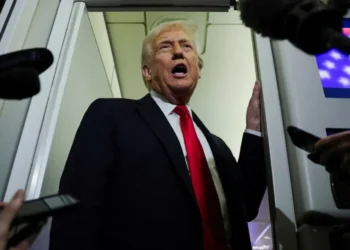

Los Angeles provided an early template. After protests erupted in June over an increase in aggressive Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids, President Donald Trump ordered roughly 4,000 federalized National Guard troops into the city and activated about 700 US Marines. At the same time, he signaled—online and through traditional media—a willingness to escalate even further by invoking the Insurrection Act. Troops stood shoulder to shoulder with long guns and riot shields as smoke canisters and crowd-control munitions blanketed highways and city streets, a posture nominally framed as deescalation and for the protection of federal property but calibrated to provoke confrontation.

Inside the Pentagon, officials rushed to draft domestic use-of-force guidance for Marines that contemplated temporary civilian detention—an unusually explicit entry into a legal gray area, paired with a highly visible show of force.

By August, the federal government shifted from episodic deployment to direct control: Trump placed Washington, DC’s police department under federal authority and deployed roughly 800 National Guard troops, exploiting the district’s unique legal vulnerability. The Washington Post described the city as a “laboratory for a militarized approach.”

The administration’s rhetoric was not subtle—Trump cast the crackdown as an image project, calling Washington a “wasteland for the world to see,” and openly endorsing fear as a policing tactic, urging officers to “knock the hell out of them.” City leaders countered that the supposed emergency was manufactured, noting that crime in the capital was at multi-decade lows. In city after city, “restoring order” became a flimsy euphemism for preemptive displays of force aimed at deterring dissent before it reached the streets.

Across Chicagoland, protest control became overtly choreographed. As “Operation Midway Blitz” intensified in September, officials erected barricades and “protest zones” around the Broadview ICE facility. State police in riot gear lined perimeters, while federal agents repeatedly fired tear gas and other projectiles into crowds, according to videos and witness accounts. The most brazen moment came when homeland security secretary Kristi Noem appeared on the facility’s roof beside armed agents and a camera crew, positioned near a sniper’s post, as arrests unfolded below.

This was performative policing at its most distilled: public safety reduced to a spectacle with vaguely defined urban threats cast as the danger being neutralized. The absurdity of the displays allowed routine acts of disorderly conduct to be perceived as folk-hero moments.

This performative turn didn’t emerge from nowhere. It displaced a quieter, less theatrical—but still controlling—model that had dominated US protest policing for decades. Policing scholars refer to it as strategic incapacitation: a practice whereby conditions are shaped so that protests can’t become effective in the first place.

Strategic incapacitation is policing by preemption. Rather than responding to crowds, police constrain when, where, and whether they can form at all. The toolkit overlaps with what protesters experienced in 2025: expansive surveillance, intelligence sharing, selective preemptive arrests, and “less-lethal” disruption—but the objective is more procedural than demonstrative. Protest is treated as an inherent risk, managed through no-go zones, curfews, press restrictions, and designated First Amendment areas designed to prevent organic growth.

The model began to coalesce in the late 1990s, as police agencies moved away from earlier approaches that had, for a time, encouraged nonviolent protest. That earlier shift reflected hard-earned lessons: violent crackdowns throughout much of the early 20th century often backfired, generating public sympathy for movements that might otherwise have remained marginal. Security-style protest policing accelerated after 9/11, driven by police intelligence units operating under national security frameworks and by lessons drawn from earlier confrontations—most notably the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle—where activists viewed negotiation as political surrender.

As formally permitted demonstrations gave way to impromptu, social-media-driven protests, police responded with expanded surveillance, tighter control of physical space, and covert intelligence-gathering efforts that relied on technologies first introduced on battlefields. The approach scaled seamlessly into the post-9/11 fusion-center ecosystem: threat assessments heavy with speculation, coordinated planning designed to constrain dissent, and information campaigns that framed protesters as dangerous outsiders.

Public sentiment became a critical lever. While Americans tend to resist overt militarization against First Amendment activity, fear of protesters reliably increases support for riot deployments, mass arrests, and force, providing a ready-made justification for escalation. Before this preemptive model took hold, protest policing had already undergone a reputational reckoning. In the 1960s, police responses relied on large shows of force—batons, dogs, fire hoses—and brutal violence against labor, civil rights, and antiwar demonstrators. By the 1970s, the costs of injuries, deaths, property damage, and political fallout pushed authorities to seek a less volatile approach.

That alternative became a bureaucratic system built on permits, advanced coordination, and predictable rules. Developed most clearly in Washington, DC, it aimed to preserve speech rights while limiting disruption through communication, restraint, and minimal use of force, with arrests treated as a last resort, when not carefully planned and prearranged. Court rulings, training programs, and standardized permitting systems spread the model nationwide. What began as a pragmatic response to cycles of unrest and force that produced little political or public-safety gain became the dominant public-order framework for decades.

Together, these shifts trace a clear arc in US protest policing—from suppression, to management, to prevention, to performance—where authority is asserted as much through optics and narrative today as it is by force.

The post How Protesters Became Content for the Cops appeared first on Wired.