This time last year, Zohran Mamdani was a little-known mayoral candidate so desperate to raise his profile that he spent New Year’s Day plunging into the icy waters at Coney Island, hoping to use the social media stunt to promote his rent-freeze pledge.

Now, as the calendar turns again this week, there is no doubt that he has New York’s attention. On Thursday, up to 40,000 people are expected to crowd City Hall to watch his swearing in as New York’s next mayor, the largest inaugural crowd in decades.

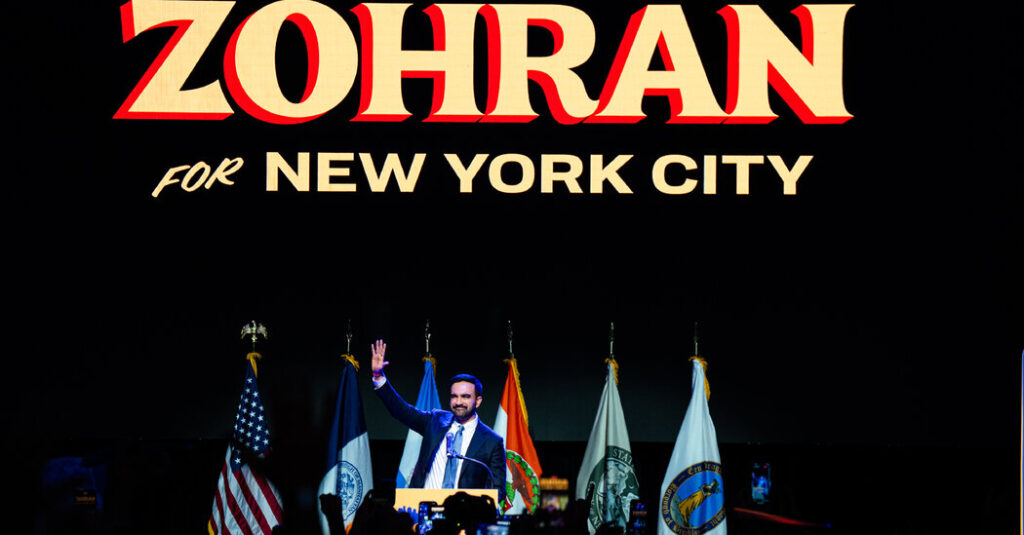

The improbable rise has already been etched into the city’s history books. With a disarming smile and targeted platform, the 34-year-old Democrat mobilized young transplants, middle-aged bodega owners and many others around an ambitious affordability platform and toppled a Democratic dynasty.

Almost overnight, his victory made him an international phenomenon, as beloved by fellow South Asians in Bangladesh as in Brooklyn, and as polarizing to Jews in Tel Aviv as in Manhattan.

On Thursday, after a two-month transition sprint, it will also officially make him the first Muslim and South Asian to govern America’s largest city, its youngest mayor in more than a century and the first democratic socialist to lead the hub of global capitalism in decades.

Yet for all the milestones and the only-in-New York boosterism that is certain to accompany the oath of office, what comes next will determine whether Mr. Mamdani will be viewed as the catalyst for a new era or as a failed idealist, soon forgotten.

His mandate is unusually clear. More than 1.1 million New Yorkers voted based largely on his promises to tame a growing affordability crisis that has made one of the world’s most expensive cities nearly unlivable for many working people. No mayor since the 1960s has won more votes.

Still, nearly a million New Yorkers voted against him, and rarely has a mayor taken office promising to deliver so much with so few assurances of needed cooperation.

Mr. Mamdani, a soon-to-be former assemblyman from Queens, will be reliant on Gov. Kathy Hochul, a moderate from Buffalo, and the State Legislature to generate the billions of dollars in new revenue needed to fund free buses, universal government-funded child care and other promises — all at a time when Washington is slashing funding to the city and state.

And as some of his predecessors have found, New York City with its eight million unruly people can sometimes seem almost ungovernable.

“Until you are in one of those jobs, you don’t understand the enormity of the day-to-day needs, and the complexity of the system,” said Steven M. Cohen, a longtime ally of and former state official under former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo, Mr. Mamdani’s chief election rival.

The opposition will be real. Small landlords are worried that Mr. Mamdani’s proposed rent freeze on rent-stabilized units could bankrupt them. Political moderates see a city hurtling toward the extremes. Many Jewish New Yorkers (though certainly not all) view Mr. Mamdani’s stark critiques of Israel as a threat to their safety.

Gerard Kassar, who leads New York’s Conservative Party, said he feared that Mr. Mamdani would make his hometown “an American test tube for tried and failed international socialist policies.”

National standard-bearers of the left, including Senators Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, have noted the stakes and become regulars in Mr. Mamdani’s transition offices in recent weeks. (Mr. Sanders is administering the oath of office at Mr. Mamdani’s inauguration.)

“If Mayor Mamdani can build child care and more affordable housing and cheaper groceries there, then we can do it anywhere else in the country,” Ms. Warren said in a recent interview.

But after the raw enmity of the campaign, there has also been a notable thaw.

Many of the wealthy business executives who wrote large checks to try to stop his election breathed a sigh of relief when Mr. Mamdani said he would reappoint Jessica Tisch, the respected police commissioner, and hire other government veterans as top deputies.

“If you are engaged in civic life, and you care about the city, it’s hard to do anything but root for a new mayor,” said Mr. Cohen, who ran a $30 million super PAC that attacked Mr. Mamdani as naïve, an enemy of the police and “radical.”

In an interview, he said Mr. Mamdani had diagnosed real problems around the cost of living in the city. “There’s a hope that new blood, a new perspective and a heightened kind of energy will make a difference,” Mr. Cohen said.

Mr. Mamdani has also labored — with mixed success — to reassure Jewish New Yorkers that he wants to be their mayor, too. He recently met with a group of rabbis and joined the actor Mandy Patinkin, and his wife, the actress Kathryn Grody, at their apartment to make latkes for Hanukkah.

(In the biggest misstep of his transition, Mr. Mamdani hired a high-level appointee who had made antisemitic comments on social media in her youth; after the Anti-Defamation League surfaced them, she was fired.)

Perhaps most surprising, though, was Mr. Mamdani’s Oval Office meeting last month with President Trump. After the president had spent months threatening to withhold billions of dollars in federal funds and send in the National Guard if Mr. Mamdani was elected, he appeared almost charmed.

“I expect to be helping him, not hurting him — a big help,” Mr. Trump said, as Mr. Mamdani stood next to him somewhat stiffly.

Many allies of the president and of Mr. Mamdani, who has called Mr. Trump a “fascist,” doubt the peace will last.

For now, though, many of Mr. Mamdani’s most ardent supporters, and even average Democrats, appear to be willing to be hopeful.

New York City, after all, has not had an easy decade, even before inflation began turbocharging living costs. Covid-19 ravaged its dense blocks, then emptied its office towers and subways. Texas and Florida have led an unrelenting campaign to lure away its wealthy residents with promises of warm winters and low taxes.

Mayor Eric Adams, who will leave office this week, became a national laugh line after he was indicted on corruption charges involving Turkish Airlines upgrades and then let off by Mr. Trump’s Justice Department. After weeks of public vacillation, Mr. Adams said on Tuesday that he would attend Mr. Mamdani’s inauguration.

Many other attendees have displayed more enthusiasm.

Humza Mehfuz, a Muslim college student who plans to attend Thursday’s festivities, said he could not have imagined someone like Mr. Mamdani in City Hall at the time of the Sept. 11 terror attacks and the rise in Islamophobia that followed.

“That would have completely taken me by surprise,” he said.

Mr. Patinkin and Ms. Grody also shared their optimism in a phone interview, with Mr. Patinkin saying he could not understand how so many Jewish New Yorkers “can be so filled with fear and blindness” as to mistrust Mr. Mamdani.

Ms. Grody, for her part, conceded Mr. Mamdani may not be able to accomplish all he has set out to in one four-year term, or even two.

“It’s an impossible job. He’s going to make mistakes,” she said. And still, she added, “If it’s two steps forward and one back, I will take those two steps forward.”

Mr. Patinkin turned to song to express his less guarded optimism. He began singing “Over the Rainbow,” slightly altering the words written almost a century ago by two first-generation Jewish New Yorkers, Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg.

“At the end of the song, I like to change the lyric,” he said. “If happy little bluebirds fly beyond the rainbow, why, oh, why can’t — we?”

“As opposed to ‘I,’” Mr. Patinkin explained. “That’s what I feel about him. That’s my prayer and my wish for him and our city of all religions, all colors, all sexes, sizes and shapes.”

David McCabe contributed reporting.

Nicholas Fandos is a Times reporter covering New York politics and government.

The post For Zohran Mamdani, a Crowning Moment, With Challenges Looming appeared first on New York Times.