When the soprano Lisette Oropesa sang the role of Elvira in a production of “I Puritani” in Paris earlier this year, her face was caked in ghostly white makeup and she spent much of the evening navigating stairs on the set’s revolving frame of a house. That sparse frame, with its Escher-like maze of steps, was meant to suggest a descent into madness by a heroine who feels trapped by her father’s demand that she marry a man she does not love.

“I had to run around the set like a bird trapped in this cage,” she said.

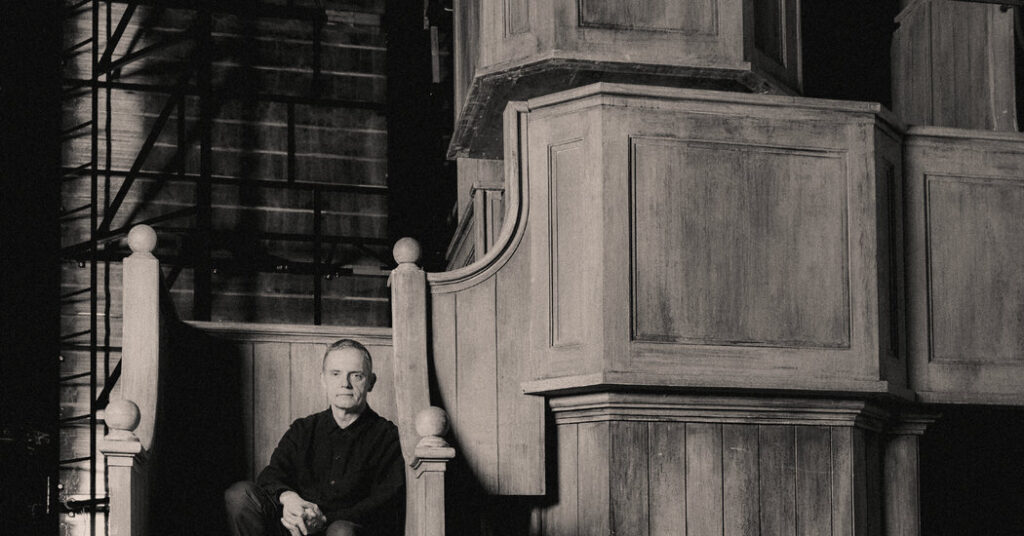

When Oropesa next sings Elvira, at the Metropolitan Opera on New Year’s Eve, she will find a set as traditional and realistic as the one in Paris was allegorical. It is a Puritan town hall in 17th-century England, depicted with pews and a pulpit constructed from distressed wood. The Puritans will be dressed in traditional garb, complete with large felt hats for the men and caps to cover the hair of women. Those fancy projections and special effects that have enlivened so many recent operas at the Met? Not for “I Puritani.”

“It is very traditional,” Oropesa said. “It’s very much — here’s the time period we’re in, here are the costumes they wore, here are the hairstyles they would have worn.”

This high-profile production, conducted by Marco Armiliato, is a paean to traditionalism from an opera company that has been increasingly adventurous as it seeks to bring new people through its doors. Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Met, called it “a retro move, but a retro move done in a very effective and compelling way that I hope will appeal to both new and old audiences.”

It has been a half-century since the Met staged a new production of “I Puritani,” the last opera Bellini wrote before he died at 33. The last one, directed by Sandro Sequi, had its premiere in February 1976, with a cast of some of the most acclaimed opera singers of the day: Joan Sutherland, Luciano Pavarotti, Sherrill Milnes and James Morris. By 2017, the last time that production was revived, it had seen better days. Anthony Tommasini, reviewing it in The New York Times, described it as “dustier-looking and duller than ever.”

Charles Edwards, a British stage designer making his Met directing debut with “I Puritani,” said he had briefly considered transporting this story into a contemporary setting: The tensions between Royalists and Puritans could parallel political tensions in the United States and in England, making the story more accessible and urgent. He decided to let the opera speak for itself.

“It is a very neat thing to be able to do: just set it in modern America or modern England,” Edwards, who is also the show’s designer, said in an interview. “But I’m afraid I don’t think the music really allows us to do that. It’s too obvious. It’s also just such an interesting period to put onstage clearly that I’d rather do that and allow the audience to come to its own conclusions.”

The production comes at a time when opera houses around the country are seeking to balance the thirst for traditional stories told in a traditional way with a desire to accommodate shifting tastes with new operas told in new ways. “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay,” the Met’s season opener, whose sets were almost created entirely by video and projections, is on one side of the scale. “I Puritani” is on the other.

Lawrence Brownlee, the tenor who will sing Arturo, also sang that role on the modernistic set in Paris with Oropesa. “I know we are in an age where everything’s become more modern,” he said, “but I think it’s OK to revisit the classic stories, told with the lens of today, but also giving homage to what the past was. There are a lot of people who still appreciate that — who still want that.”

Gelb said that the Met was “trying to have it both ways” by appealing to both audiences, and that this production was evidence of that.

As popular as it is with bel canto audiences and singers, not to mention directors like Edwards, “Puritani” can be daunting with its musically demanding score for four lead singers (Artur Rucinski and Christian Van Horn round out the cast) and a story that is convoluted even by the standards of 19th-century opera. It has been performed just 63 times at the Met; by contrast, Bellini’s “Norma,” has been done 175 times. (Edwards, among others, argues that the mad scene in “Puritani” is even more gripping than the mad scene in “Norma.” )

“A lot of people think ‘Puritani’ has a stupid story,” Edwards said. “I do not. In those days, people went to opera to be thrilled, to see something unexpected. To see something emotionally charged and extreme. They didn’t go to see a well-made play.”

Gelb said he originally asked David McVicar, one of the Met’s most prominent directors, to take on this project. McVicar was not available, but he suggested Edwards, whom he had worked with as a set designer on operas including “Fedora” in 2023 and “Il Trovatore” in 2009 and who has directed operas in Europe.

“The humanity of ‘Puritani’ made it incredibly accessible to me,” Edwards said, “and the fact that it’s about my own country, and the subject matter connects in a way to a period that we don’t talk about much in English history.”

This is an opera that the audience on New Year’s Eve is more likely to have heard than to have seen, or at least seen recently. Because of that, Oropesa, after her time in Paris, applauded the decision by New York to take the more traditional route.

“I think the issue with these operas is because they don’t get done a lot, they don’t have space for reimagining so much,” she said. “That’s why a perfectly literal, straightforward production makes sense — not a big showcase of ‘look at all this new technology’ or ‘we’re going to set it in some daring time period.’”

Adam Nagourney is a Times reporter covering cultural, government and political stories in New York and California.

The post At the Met, Toasting With Traditional Puritans on New Year’s Eve appeared first on New York Times.