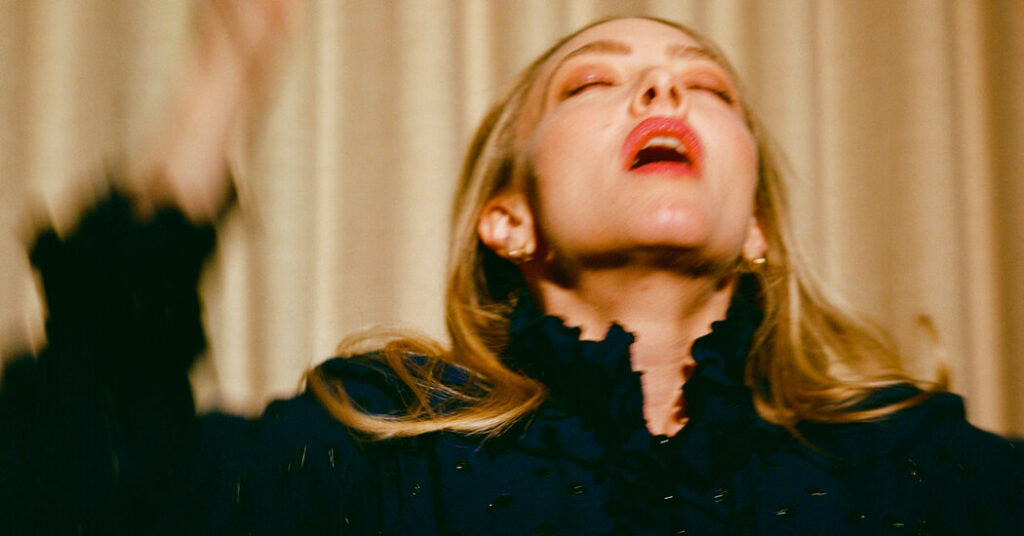

Breath is the key. Movement flickers in Amanda Seyfried’s eyes before flowing through her body as she exhales, her breath, tentative at first, becoming stronger and more emphatic. She tosses one arm into the air and then the other before twirling and joining in the collective rhythm of the people around her whose hands, like bouncing balls, fall and rebound on their chests.

In “The Testament of Ann Lee,” Seyfried plays the founder of the Shakers, the 18th-century religious sect named for the shaking and ecstatic dancing that characterized their worship. Directed by Mona Fastvold, the movie comes to life through music and dance to create a new kind of musical, passionate yet never overly performative.

Fastvold’s film tells the story of Lee’s life — born in Manchester, England, in 1736, she was a feminist who fought for equality for the sexes. But beyond that, Fastvold was struck by the Shakers’ embodiment of music and movement. “There were descriptions of, for lack of better words, rave parties that they would throw for days on end in Manchester, where they would just dance and dance and move and sing and shake and improvise vocally and physically,” she said in an interview with Seyfried and Celia Rowlson-Hall, the film’s choreographer. “Until people would call the cops and have them dragged away.”

Lee had four children who died in infancy. The trauma of losing her children led her — and the Shakers — to commit to celibacy, which promised a greater spiritual connection to God and promoted equality between the sexes. As a woman working against society’s norms to build a utopia, Seyfried, the film’s grounding force, is singular in her devotion.

Seyfried’s body and voice seem ignited from within. It was a blessing, she said, “to be able to explore something and live through their experience with movement — you’re so present.”

That idea of presence is integral to the dancing in “Ann Lee,” which has less to do with codified steps than surrendering to a higher power. Here, the Shakers play their bodies like instruments. Their arms — floating, suspending, swinging — are like wings, angelic and wild, as they try, ecstatically, to fly toward the divine. By the end, when the group settles in America, the choreography is less raw and more steady, reflecting the clean lines of Shaker design.

Seyfried, who starred in two “Mamma Mia!” films, can sing and dance, but the choreography in those movies was different. “It’s sugary sweet, it’s fun, it’s exciting, it moves you,” she said. “But this is more human. It took me a long time to connect to that part of the movement for me. But once you really know it, it’s a whole other tool. I’ve never gotten the opportunity to convey all these things with this type of physical expression.”

In “Ann Lee,” the choreography and songs — by the composer Daniel Blumberg who used Shaker melodies as a foundation for the music — are embedded in the storytelling, perhaps most dramatically in a scene of the group traveling across the Atlantic Ocean by ship during a storm. The Shakers sing the hymn “All Is Summer” on deck — through drenching rain and, later, snow — pounding their fists on the deck, rising angelically and linking arms for circle dances. It becomes a prayerful dance of fortitude. (Yes, they make it out alive.)

While Fastvold was writing the script with her husband, Brady Corbet — who directed “The Brutalist,” also written together — she was thinking of Rowlson-Hall, whose earthy movement, with prickly depth and sensitivity, can peel back surface emotions to reveal a character’s inner world. (The two worked together on “Vox Lux,” 2018.)

Rowlson-Hall was inspired by illustrations Fastvold found showing the formations of the Shakers in prayer. There were pencil drawings and paintings of the circular dance movements. Fastvold also found reconstructions of the movement on video, but, she said, “They seemed like their own interpretation.”

The choreography is mainly born from Rowlson-Hall’s imagination. “We were going through images and descriptions of these rave parties and just thinking, ‘To dance all through the night, not on drugs, not having sex — like wow,’” Rowlson-Hall said. “Where does the body get to go in this? And what’s propelling you and giving you that energy as you feed off the other people?”

The tone of the dancing was crucial. “It’s never a performance,” said Fastvold, who trained as a ballet dancer. “It’s never for anyone but you. My ultimate fear was that the dance would feel like a snappy number, like, ‘Look at this cool thing we’re doing here.’ It’s never about showing you some fabulous choreography.”

Instead the choreography is an extension of human expression: worship, pain, love and the lifelong grief that Lee suffered from losing her children. The cast includes both trained and untrained dancers. “What matters is that they knew what the movement meant,” Fastvold said. “It’s not about doing it right or wrong, it’s about intention.”

Though Seyfried is front and center, the cohesion of the group is essential, and if the intention of any of the dancers wavered, Fastvold added, “This whole collective experience would completely falter.”

Seyfried, as fluidly expert as she seems in the film, has little dance training. “I was in the third row of dance team,” she said dryly, and she took ballet classes as an adult in Los Angeles.

But working on “Ann Lee,” Seyfried, a trained singer, found a new relationship to her voice through Rowlson-Hall’s choreography. The process was life changing, she said, “in terms of how I relate to my body as a singer.” Her self-criticism melted away. She felt liberated.

While shooting the somber song “Beautiful Creatures,” she tried different approaches. “I would scream through the song, I would cry through the song, I would whisper through the song,” she said. “I got to explore all ways of making noise — primal, instinctual, angry, emotional, whatever it is.”

The result is gutting in the way that all of those textures, like frazzled emotions, remain.

In “Ann Lee,” the voice and the body become one, and movement is a part of the music. “Every exhale is in the songs,” Fastvold said. “Normally you would take that out. We make space in the music for the sound of her hand, her finger against the floor. I wanted the movement and the breaths and the world and the rain and the wind and the foot slips on the stomps and all of that continue to be equally represented.”

Rowlson-Hall realized that as Seyfried and the cast focused on their vocalization as they moved, she said, “It unlocked something. The way that I like to approach it is the more that I can take the dance away, then the more it can just be her moving through her life — her body and her grief and her joy.”

She didn’t run rehearsals in the usual way, repeating the choreography until it was fluent. “That’s not what it is,” Rowlson-Hall said. “It’s like if we found the container, and you’re holding all of that in, then go. I actually don’t care what it looks like because you are living in it honestly. And so it was very much like, this is what I’ve created. It’s yours now.”

Gia Kourlas is the dance critic for The Times. She writes reviews, essays and feature articles and works on a range of stories.

The post In ‘Ann Lee,’ Dance Is the Fuel for a Godly 18th-Century Rave appeared first on New York Times.