The egg has become a dominant source of anxiety for many women. Human eggs are finite, declining in both quality and quantity with age. In a woman’s 30s, this starts to make it harder to get pregnant, and by menopause, a woman is without functional eggs. Growing awareness of this reproductive reality has led to a surge in egg freezing, as women aim to preserve the vitality of their younger eggs.

But there’s more to infertility than old eggs. Recent research is bringing greater attention to the ovaries.

An expanding body of evidence suggests that the age of an ovary, not just the eggs it contains, is important to reproduction and healthy aging. That includes the cells and tissues that make up the environment around a woman’s eggs, such as support cells, nerves and connective tissue.

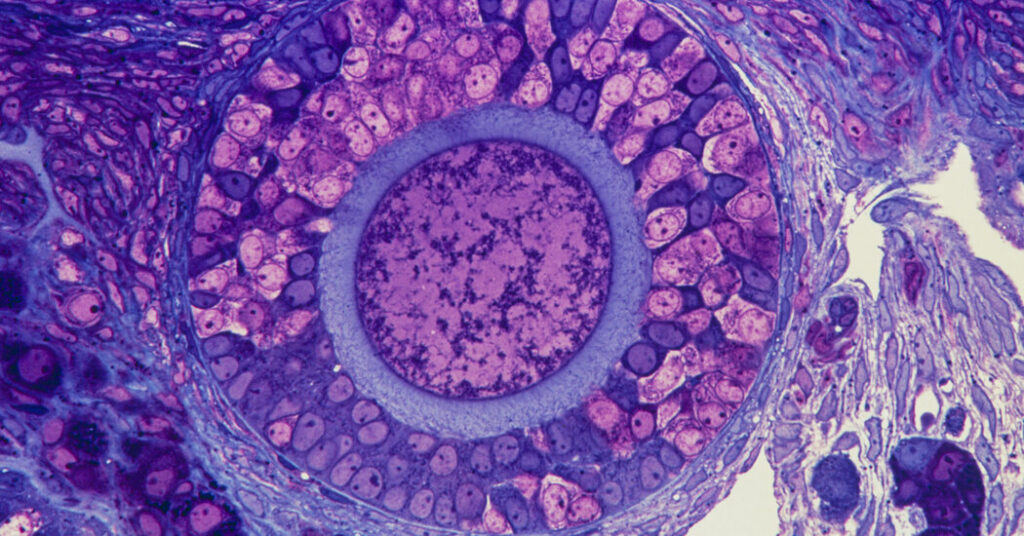

The tissues surrounding the follicles — fluid-filled sacs that contain an immature egg — can change with age, even becoming fibrotic. Research has shown that this can harm the quality of eggs, reduce the number that mature each month and block ovulation. Fibrosis is common in many aging organs as thick, scarlike tissue builds up. But it occurs decades earlier in the ovaries.

As scientists seek treatments for age-related infertility, as well as menopause, they need to understand the ovary’s full cast of characters.

“You cannot separate the health of the egg from the health of the other cell types,” said Evelyn Telfer, the chair for reproductive biology at the University of Edinburgh.

Your Questions About Menopause, Answered

Card 1 of 8

What are perimenopause and menopause? Perimenopause is the final years of a woman’s reproductive years that leads up to menopause, the end of a woman’s menstrual cycle. Menopause begins one year after a woman’s final menstrual period.

What are the symptoms of menopause? The symptoms of menopause can begin during perimenopause and continue for years. Among the most common are hot flashes, depression, genital and urinary symptoms, brain fog and other neurological symptoms, and skin and hair issues. Here’s a head-to-toe guide to the midlife transition.

How can I find some relief from these symptoms? A low-dose birth control pill can control bleeding issues and ease night sweats during perimenopause. Avoiding alcohol and caffeine can reduce hot flashes, while cognitive behavioral therapy and meditation can make them more tolerable. Menopausal hormone therapy and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine can also ease some symptoms.

What is Veozah? Veozah is the firstnonhormonal medication to treat hot flashes in menopausal women; it was recently approved by the F.D.A. The drug targets a neuron in the brain that becomes unbalanced as estrogen levels fall. It might be particularly helpful for women over 60 because, at that age, starting hormonal treatments can be considered risky.

How long does perimenopause last? Perimenopause usually begins in a woman’s 40s and can last for four to eight years. The average age of menopause is 51, but for some it starts a few years before or later. The symptoms can last for a decade or more, and at least one symptom — vaginal dryness — may never get better.

What can I do about vaginal dryness? There are several things to try to help mitigate the discomfort: lubricants, to apply just before sexual intercourse; moisturizers, used about three times a week; and/or estrogen, which can plump the vaginal wall lining. Unfortunately, most women will not get 100% relief from these treatments.

What is primary ovarian insufficiency? The condition refers to when their ovaries stop functioning before the age of 40; it can affect women in their teens and 20s. In some cases the ovaries may intermittently “wake up” and ovulate, meaning that some women with primary ovarian insufficiency may still get pregnant.

Fact, or fiction? We asked gynecologists, endocrinologists, urologists and other experts about the biggest menopause misconceptions they had encountered. Here’s what they want patients to know.

In other words, the egg may be the leading lady, but she needs her supporting cast.

The ovary is an exceptionally dynamic organ. It’s both a reservoir for eggs and a producer of hormones that usher egg-containing follicles through the complicated biological choreography known as folliculogenesis. That is ultimately what results in monthly ovulation. Follicles are surrounded by supporting tissues within a skeletal-like structure called the extracellular matrix. These tissues and the cells they contain, together called the stroma, are the focus of recent research.

In 2014, in the lab of Francesca Duncan at the University of Kansas Medical Center, a technician pointed out something peculiar while studying the development of early-stage ovarian follicles. In older mice, the surrounding tissue appeared to stiffen, making the follicles more difficult to extract.

In her training as a reproductive biologist, Dr. Duncan had learned to disregard most components of the ovary — everything besides the egg and its follicle was literally trashed. But what she observed in the mice made clear that other tissues might be critical to the egg’s development.

“The egg needs this whole village,” said Dr. Duncan, now a professor of reproductive science at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

The follicle itself produces the key hormones that drive an egg’s development, but newer work has shown that the ovaries’ other tissues can influence the production of those hormones.

Recent research has shown that if mouse follicles growing in a dish are suspended in stiffer substances, the follicles produce different hormone profiles, and ultimately worse eggs. The environment of the ovary, in other words, directly influenced the quality of the egg.

Another Northwestern researcher, Monica Laronda, has found that aging may be influenced not only by follicular hormones, but also hormones produced by the stroma. At least some of those stroma hormones appear to increase with age. In other research, published online in September ahead of submission to a peer-reviewed journal, Dr. Laronda found that putting ground-up human ovarian stroma in a petri dish with mouse follicles improved the growth of the follicles. It’s another data point indicating that these tissues are needed for healthy eggs and ovaries.

In a recent comparative study of human and mouse ovaries across age, Diana Laird of the University of California, San Francisco, found that the density of sympathetic nerves surrounding follicles in the ovary increases with age. At the same time, the blood vessels around follicles begin to decrease in density. She said those could be key signals of follicular wellness and overall health. She hopes to design a blood test that can assess the health of a woman’s ovarian reserve.

All of these insights point to new ways to treat not only infertility, but also potentially delay harmful side-effects of menopause, like bone density loss and heart disease risk. Work from Rebecca Robker, a reproductive biologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia, has demonstrated that ovarian fibrosis could be reversible. In a 2022 study, she showed that a drug used to manage pulmonary fibrosis prompted ovulation in older mice.

Dr. Duncan’s lab is now testing anti-fibrotic drugs that could benefit ovarian health. Such treatments may one day be given to patients struggling to conceive before trying IVF, or even to women hoping to delay menopause.

Drugs popular among longevity enthusiasts, such as metformin and rapamycin, are also being studied to see if they can slow ovarian aging. GLP-1s have shown potential to improve fertility, too. All of these drugs may work in part by decreasing ovarian fibrosis, said Kara Goldman, a reproductive endocrinologist at Northwestern.

But in many ways, the ovary remains enigmatic. Scientists still don’t understand many of the molecular signals and cellular interactions that drive egg development and aging. Because the ovary ages faster than any other organ in the human body, understanding it could lead to breakthroughs in our understanding of aging, said Jennifer Garrison, a neuroscientist and assistant professor at UCSF’s department of cellular and molecular pharmacology.

“The ovary is complex,” she said. “It’s important not to dumb it down.”

The post It’s Time to Give the Ovary Some More Respect appeared first on New York Times.