As the city fails them — there’s a new beacon of hope for the homeless population of LA’s fentanyl-fueled MacArthur Park — a local business owner digging into his own pockets to get these desperate people a ticket home.

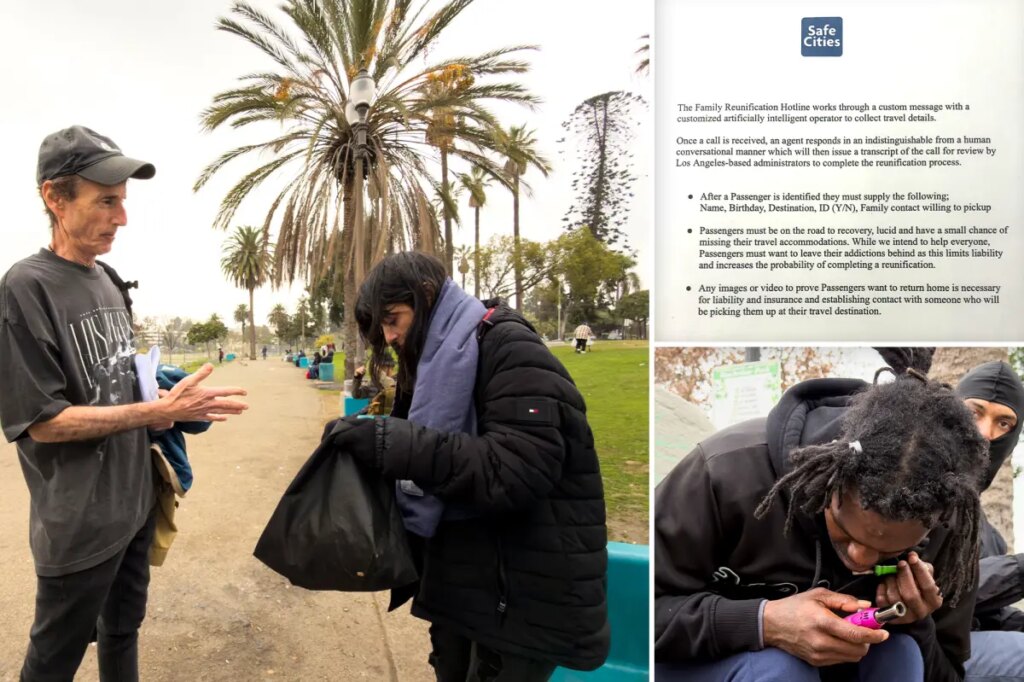

This park didn’t collapse by accident,” John Alle said, handing out flyers into open hands as the chaos churned. “It fell off a cliff because of ideology. City Hall refuses to act — so we do it ourselves.”

Alle runs Safe Cities, a no-frills reunification effort built around one unforgiving idea — get people stranded on the streets of Los Angeles back to their families for good. No housing roulette. No cash handouts. No nonprofit middlemen. Just verified contacts, strict rules, and a one-way ticket home.

“We handle transportation. Period,” Alle said. “Bus, train, plane. That’s it. We don’t warehouse people. We don’t hand out money. We get them back to the people who actually care about them.”

In just four months, the privately funded effort has already sent 36 people home, with what Alle says is a 100% success rate.

Most of the people he encounters, Alle says, aren’t deeply entrenched in drugs, sex work, or violent crime — they’re disconnected, still reachable, and running out of time.

Inside MacArthur Park, the city’s experiment is on full display.

The Post toured the historic park once again Tuesday and witnessed how it has morphed into a grim, drug-riddled sprawl — tents jammed against walkways, dealers posted openly, addiction operating at street level with government-funded tools.

A woman locked in a violent fentanyl spiral screamed uncontrollably while others — many young, hollow-eyed and shaking — crouched low, loading pipes for their next hit. Needles flashed in the dirt. Pipes passed hand to hand. Open-air drug deals unfolded without urgency, barely registering to people too consumed to look up.

The damage was written on bodies. Hair matted and filthy. Fingernails black with grime. Skin blistered raw from months of sleeping on dirt and concrete. Some shuffled barefoot across damp grass despite the cold, feet cracked and swollen. Addiction wasn’t hidden — it was the organizing principle.

MacArthur Park sits in the district of Councilwoman Eunisses Hernandez, whose tenure has coincided with the park’s accelerating collapse. City Hall and Hernandez’s district have poured more than $27 million into the area for homelessness initiatives — including outreach contracts, on-site programming and the distribution of drug paraphernalia like crack pipes.

The New York Post has sought comment from Hernandez for more than two weeks since reporting began on conditions inside the park. She has not responded.

Midway through the walk, Alle stopped to speak with a woman who said she was flown to Southern California for rehab, lost her placement and slid straight into homelessness. Her family is in Alabama.

“I’ll have a year sober in April,” she said. “I fight it every day.”

She said the park makes staying clean feel nearly impossible. When Alle asked how often dealers or recruiters approach her, she didn’t hesitate.

“Every day. Several times a day.”

She condemned a system she said feeds addiction instead of stopping it.

“You should be offering people help — not aid,” she said. “If someone had enabled me when I was using, I’d be dead.”

She also alleged identity theft is rampant, saying a government-issued phone in her name was flipped for cash, cutting her off from basic services. None of it surprised Alle.

“This system doesn’t just fail people,” he said. “It feeds on them — keeps them stuck while politicians posture and bureaucracies swell.”

Working entirely on private donations, Alle often spends just a few hundred dollars to deliver a permanent solution — a verified ticket home, out of Los Angeles and off the streets. His rules are strict: stay clean, get to the airport, verify who’s receiving you — and don’t come back.

Fresh off a successful reunification the week before, he was hoping for another — a home-for-the-holidays ending.

“Family is the support system,” he said. “Not the street. Not the park. Not a tent.”

After about ten minutes, Alle laid out his offer. The woman’s voice cracked. She said she was ready. He told her to call her family and start the process — he would do the same on his end.

Not everyone was there yet. A 29-year-old woman from Massachusetts waved him off, gesturing toward the steady flow of handouts in the park — pipes included. Her family, she said, won’t take her back unless she’s clean.

For those still deep in addiction, the park doesn’t just trap them — it grips hard, offering just enough to keep them exactly where they are.

No ticket that day. Just a flyer, a phone number — and a shot at escape.

“She’ll take it,” Alle said. “I can tell when they’re ready.”

The post While LA torches $27 million at drug addict park, one man buys the homeless an exit one ticket at a time appeared first on New York Post.