CAPTIVES AND COMPANIONS: A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World, by Justin Marozzi

When the British journalist Justin Marozzi was covering the 2011 uprising in Libya, he encountered something that profoundly confused him. Meeting in Tripoli with a group of rebels, he heard one turn to a Black comrade and say, “Hey, slave! Go and get me a coffee!”

As Marozzi writes in “Captives and Companions,” his knotty history of slavery in the Middle East, the other rebels were “clearly” amused, even if “it was equally clear” that their comrade was not.

The practice of slavery persists in the Middle East today in shadowy forms. In Lebanon and Qatar, for instance, the “kafala system” cycles African migrants into coercive contracts as maids or construction workers. But what most galled Marozzi in 2011 wasn’t a case of actual servitude; it was the fact that the term “slave” was still in regular use, even outside its original context. How did such casual utterances relate to the thousand-year legacy of bondage in the region?

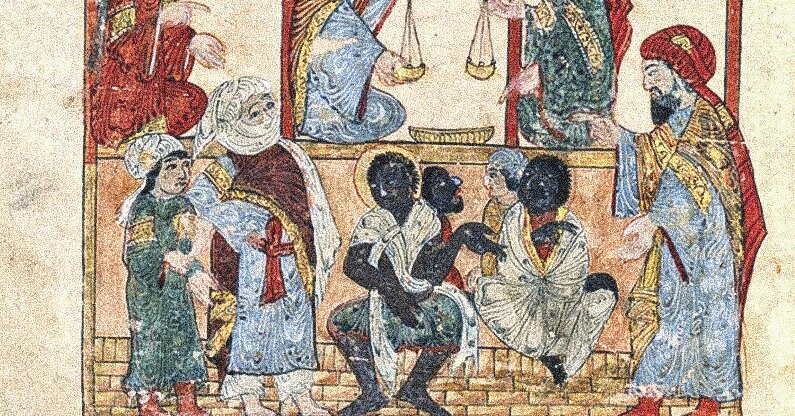

As Marozzi explores this question in “Captives and Companions,” he showcases the many types of enslaved people — eunuchs, harem women, mercenaries, unpaid laborers — who populated a region that stretches across modern-day Libya, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Oman and Saudi Arabia, all the while demonstrating how the realities of bondage in these places differed from the more familiar chattel slavery of the West.

Until the late 19th century, slavery was a near universal institution, though it was practiced in so many varieties that the word could hardly encompass them all. Marozzi’s account begins in 632 with a “free-spirited woman” in the first caliphate who took a slave to bed, assuming it was her right as set forth in the Quran. The story runs all the way up to the present, when the author visits a man who labors without pay for a master in Mali.

Marozzi refers to his scope of interest as the “Islamic world,” apparently because slavery, like so many other iniquities, was justified by the existence of rules found in religious codes. The Prophet Muhammad, like Abraham, was an untroubled owner of slaves, and “the legitimacy of the slavery, as pronounced upon by the Quran, is not up for debate,” Marozzi writes.

But were Quranic precedents and injunctions decisive? As the author himself is quick to note, almost no one followed the official guidance about slavery, especially rules proscribing rights for the enslaved, which Marozzi tells us were the most “progressive” of the Abrahamic religions. “While Christians professed equality before God, Jews offered reduced penalties for adultery with slaves and Romans prohibited slave prostitution,” he observes, “only the Quran did all three.”

Selective obedience to scripture was not exclusive to Muslim slavers. As historians such as John Samuel Harpham and James McDougall argue in a pair of new histories, European and Middle Eastern elites grounded their attitudes toward slavery not only in religious texts, but also in opposing ancient conceptions — Roman law held slavery to be a case of bad luck for the enslaved; Aristotle, meanwhile, had argued that some people were slaves “by nature.” As material interests shifted, the metaphysical emphasis tended to change to suit them.

Despite its subtitle, the most satisfying parts of Marozzi’s book come not in its winding passages of religious or secular exegesis, but in the moments of high-flying T.E. Lawrence-style storytelling, where the author describes the messy ways in which slavery unfolded in the Middle East. We learn for instance about the sixth-century swashbuckler Antara ibn Shaddad, “who managed the transition from Arab-Africa slave to chivalric knight, ferocious warrior, paragon of manly virtue and romantic, hell-raising poet before his death on the cusp of Islam’s arrival on the Arabian Peninsula.”

The fate of Beshir Agha was even more dramatic. Born around 1655 in Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia), he was captured as a boy and forced into service as a eunuch in the Turkish court, where he became, according to some accounts, the most powerful man in the Ottoman Empire, “a ruthlessly effective maker and unmaker of viziers.”

Still, such trajectories were a rarity. Most enslaved people over the span of the centuries were held in bondage for life, and treated inhumanely by their owners.

How significant was racism in the practice of slavery by Muslims? Marozzi suggests that the advent of racial prejudice in the Middle East might have preceded the rise of modern European racism by several centuries. He quotes, for instance, the 13th-century Persian philosopher Nasir al Din al Tusi: “The Negro does not differ from an animal in anything except in the fact that his hands have been lifted from the earth.”

Marozzi also finds a preference for white skin all over Muslim literature and commentaries, going as far back as the 14th-century Arabized Berber writer Ibn Khaldun, though how well a few selected medieval texts correspond to the attitudes of millions of everyday people across millions of acres of land seems rather murky.

Having traveled to most of the countries he writes about, Marozzi is aware of the pitfalls of his project. He appears to know how easy it is to descend into lazy generalizations about Islamic culture, and, in doing so, to prop up Western self-regard. Nevertheless, Marozzi appears reluctant to wriggle free from some of the most robust myths of the Victorian age. For instance, he argues that the Ottoman slave trade “did not die a natural death.” Instead, “under unrelenting European pressure, it withered for decades in the 19th century before eventually dying in the 20th.”

That may be how it looks to Western eyes, but the Ottomans had their own reasons for terminating the trade, however haltingly. Nineteenth-century Ottoman reformers needed little encouragement to eradicate a slave system presided over by the very elites they wanted to overthrow. Local abolitionist bureaucrats, Islamic rulings sanctioning abolition and changes in agriculture all likely contributed as much to the end of Ottoman slavery as the chiding of British officials dispatched to the empire in the 1840s and ’50s.

Marozzi prefers not to think too closely about his book’s assumption. “Our story is not about historians,” he writes. “Nor is it a history of history.” But, to borrow a phrase, journalists who declare themselves exempt from the influence of historiography are often the captives of some defunct historian.

In the case of Marozzi, that historian may be the Princeton professor Bernard Lewis, whose “Race and Color in Islam,” published in 1971, sought to undermine the solidarity between Black American radicals like Malcolm X and Middle Eastern Muslims. Contrary to the universalist ideal that Malcolm had found in Islam, Lewis wrote, there was a long history of prejudice against dark-skinned people in Arab societies.

Two decades later, in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,” a book that Marozzi happily cites, Lewis updated his thesis to dispel the notion that people in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan were innocent victims of European imperial might. Instead, he suggested, the pervasiveness of slavery in the Middle East showed they had been practitioners of evil all on their own. Unsurprisingly, Lewis became a favorite court scholar of the George W. Bush administration as it prepared to invade Iraq.

“Captives and Companions” is a more engrossing and less polemical read than Lewis’s books, and Marozzi deserves credit for lighting up a vast subject with vivid tales that throw Atlantic slavery sharply into relief as the more historically startling development.

Yet readers of “Captives and Companions” should be cautious with what they do with their discomfort. At the turn of the 20th century in the Congo, King Leopold II of Belgium launched an enslavement campaign that would leave 10 million people dead. It was not for nothing that he declared his mission was to eradicate Arab slavery.

CAPTIVES AND COMPANIONS: A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World | By Justin Marozzi | Pegasus | 524 pp. | $35

The post How Should We View the Middle East’s Legacy of Slavery? appeared first on New York Times.