Key takeaways

- The Supreme Court is far more focused on cultural political issues such as religion, guns, LGBTQ rights, and abortion than it was in the recent past.

- The current Court is hearing more than twice as many cases that touch on these issues than it did during the Obama administration.

- There are several reasons why, including the justices’ own interest in cultural politics, the fact that right-leaning lawyers are more likely to bring lawsuits seeking to change the law when they have a friendly Court, and the fact that the justices have made so many recent changes to the law that they often have to clarify how their new legal rules work.

The Supreme Court for much of the last several decades has been a fairly technocratic body.

The Court, to be sure, has handed down its share of historic cases: Case names like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and Roe v. Wade (1973) are familiar to most Americans, but such highly political and culturally salient cases have historically made up only a small percentage of the Court’s work.

We live in a different world today. In its 2024-25 term alone, the Court is expected to gut what little remains of the Voting Rights Act, to legalize anti-LGBTQ “conversion therapy” in all 50 states, to permit states to bar transgender athletes from school sports, to give President Donald Trump near-total control over “independent agencies” that Congress insulated from the president, to expand gun rights, to decide whether Trump can unilaterally strip Americans of their citizenship, and to determine the fate of Trump’s multitrillion-dollar tariffs.

One way that the Court has changed is that the current panel of nine justices appears to be fixated on culture war issues such as religion, guns, LGBTQ issues, and abortion. Though these four issues do not exhaust the many cultural divides that drive much of US politics, they capture many of the Republican Party’s current cultural grievances. And the current Court, which has a 6-3 Republican majority, now hears more than twice as many cases touching on these four issues than it did during, say, the Obama presidency.

During those eight years under President Barack Obama, the Court heard a dozen cases that focused on those issues. By contrast, in the five Supreme Court terms that began with Republicans controlling six votes on the Court (2021-present), it has heard 18 cases that focus on these issues. That works out to 3.6 cases per Supreme Court term, compared to 1.5 under Obama.

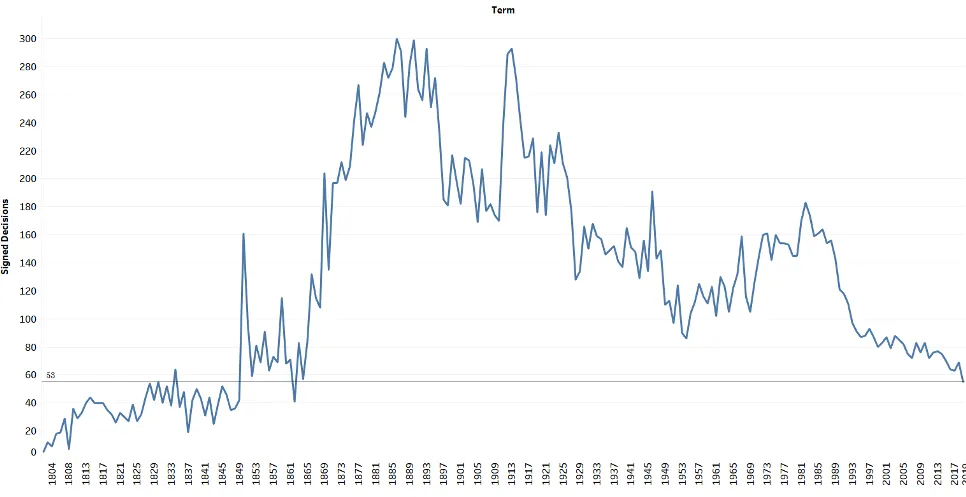

This is true even as the number of cases heard by the justices has been in steady decline since the 1980s. When Chief Justice John Roberts was a young attorney in the Reagan White House, he once quipped that it is reassuring that “the court can only hear roughly 150 cases each term.” But the Court hasn’t heard anywhere near that number for years. In its 2024-25 term the Supreme Court decided just 62 cases that received full briefing and an oral argument.

So the justices are hearing more and more politically charged cases, even as their overall workload declines.

The Court’s growing interest in cultural politics won’t surprise anyone who has paid close attention to the Court. In the last few years, the Court’s Republican majority appears to have been going down a checklist — identifying 20th-century precedents that are out of favor within the GOP, and overruling those decisions. This is the period when the Court abolished the constitutional right to an abortion, banned affirmative action on nearly all college campuses, and gave itself a veto power over the executive branch’s policy decisions, among other things.

The shifting docket reveals a Court that sees — and is seizing — many opportunities to reverse, or at least reconsider, some of liberals’ biggest cultural wins.

The Court’s new obsession with the culture wars, by the numbers

To assess just how the Court’s attention has shifted, I looked at two separate periods.

I examined all eight of the Supreme Court terms that began while Obama was president, meaning the term that began in October of 2009 through the term that began in October of 2016. I also examined the 2021-22 through 2025-26 terms — the five full terms after Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation in 2020.

Overall, I identified a dozen “culture war” cases that the Court decided during the Obama terms, and 18 that the Court decided (or will decide) in the five most recent terms. You can see the cases I identified in this spreadsheet.

Methodology

I looked at cases concerning four issues — abortion, guns, LGBTQ rights, and religion. Here is how I defined those four categories:

- Abortion: I coded a case as an abortion case if the Court’s holding determined the substantive rights of abortion providers or patients seeking an abortion. I excluded cases where abortion was mentioned, but the legal issue before the Court was jurisdictional or procedural. One example of a case that I did not include is FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (2024). Although the plaintiffs in that case sought to ban a popular abortion drug, the Court held that the federal judiciary lacked jurisdiction to hear the case.

- Guns: I limited this category to cases involving the scope of the Second Amendment. I excluded cases interpreting statutes that regulate guns or that criminalize some forms of gun use or possession, largely because the courts hear a large number of criminal prosecutions involving gun offenses that are not especially political.

- LGBTQ: This category includes cases where the Court determined the substantive rights that LGBTQ people enjoy because they are gay, bisexual, or transgender. It excludes cases where sexual orientation or gender identity are mentioned, but they are only incidental to the legal issue before the Court.

- Religion: This category includes two sets of cases; the first is cases interpreting the Constitution’s guarantees that everyone may freely exercise their faith, and that the government shall not establish a religion. I also included cases interpreting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, both of which are statutes that Congress enacted to restore constitutional rights that the Supreme Court diminished in Employment Division v. Smith (1990).

One consequence of these definitions is that some high-profile cases are excluded. I did not code Snyder v. Phelps (2011) as either an LGBTQ case or a religion case, for example, even though that case concerned a church group that held up signs with anti-gay slurs outside a military funeral. The reason is that the legal question in Snyder neither involved the Constitution’s religion clauses, nor did it involve the substantive rights of LGBTQ people. Instead, it was a free speech case and the Court almost certainly would have reached the same result if this church group had held up equally offensive signs that did not target gay people.

Similarly, I did not include Garland v. Cargill (2024), a statutory guns case that legalized “bump stocks,” devices that can convert a semiautomatic rifle into an automatic weapon, because that case did not raise a constitutional question.

In coming up with these lists of cases, I made several judgment calls. Although Justice Barrett was confirmed in late October 2020, for example, I did not look at the 2020-21 term because the Court typically decides which cases it will hear months in advance, so Barrett played no role in choosing many of the cases that the Court heard in that term. I wanted to compare the mix of cases the Court took before Trump made any changes in its membership to the mix of cases it took after all three of the justices he appointed joined the Court.

I also only included cases that received full briefing and oral argument, and excluded cases handed down on the Court’s “shadow docket,” a mix of emergency motions and other matters the Court decides on an expedited basis and often without explaining its decision. (Had I included shadow docket cases, the numbers would show that the current justices are even more interested in weighing in on cultural grievances than their Obama-era counterparts, as the Court started deciding significantly more cases on its shadow docket under Trump.)

The cases I included all fit into at least one of four categories: abortion, guns, LGBTQ rights, or religion. If you want to know how I define these four categories, I explain it in a sidebar to this essay.

The Court now routinely weighs in on issues that it rarely touched under Obama

Although the Supreme Court now hears religion cases more often than it did under Obama — a trend that is even more pronounced if you include shadow docket cases — religion has always been an important part of many Americans’ identity. So the Court has heard a steady diet of religion cases for quite some time.

Eight of the 12 culture war-related cases I identified from the eight Supreme Court terms that began under Obama are religion cases. So, even under Obama, the Court was hearing about one religion case each term, including very significant and politically contentious cases like Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), which held that employers with religious objections to birth control may refuse to include contraception coverage in their employees’ health plans.

By contrast, prior to Barrett’s confirmation it was a fairly monumental event when the Supreme Court announced it would hear an abortion case. The Court decided only one such case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), during all eight years of the Obama presidency.

Since Republicans gained a supermajority on the Court, by contrast, they’ve handed down three abortion decisions: Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson (2021), Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), and Medina v. Planned Parenthood (2025). In each case, the Court ruled against the pro-abortion rights side.

Similarly, the Court decided only one Second Amendment case under Obama, McDonald v. Chicago (2010). Indeed, the Court used to hear Second Amendment cases so infrequently that Justice Clarence Thomas complained in a 2018 dissenting opinion about his Court’s “continued inaction” on the right to own a gun.

By contrast, the Court’s current majority has decided two such cases, and it plans to hear two more in its current term.

So why is the mix of cases heard by the Court shifting?

It’s likely that the most important factor driving the Court’s new focus is that the justices typically get to choose which cases they hear, and so justices in the majority can simply pick cases that advance their political and policy goals.

Republicans have campaigned against Roe v. Wade for decades; it makes sense that the Court took up Dobbs, the case that overruled Roe, less than a year after Republicans gained a supermajority on the Court.

Another factor is, as the Court’s rightward majority becomes more secure, justices in that majority risk much less when they take up a contentious case. For many years, the Court was split between four anti-abortion justices, four who supported abortion rights, and Justice Anthony Kennedy, who voted to uphold many abortion restrictions but who also refused to overrule Roe. So it’s likely that the eight justices with firm views on the right to terminate a pregnancy avoided abortion cases because they could never be sure if Kennedy would vote against them.

Now, by contrast, the six Republicans often vote as a bloc. And when one of them does dissent from their fellow Republicans, it is often on narrow grounds. In Dobbs, for example, Chief Justice John Roberts did not vote to overrule Roe, but he did vote to restrict abortion rights and his opinion largely argued that the Court should have taken a more incremental approach to dismantling Roe.

Another likely reason why the Court is hearing so many cases that focus on Republican cultural grievances is that both litigants and state lawmakers typically shift their behavior when they perceive the Court moving left or right. A 6-3 Republican Court means that anti-abortion laws that would have been blocked by judges just a few years ago will instead take full effect. And it also means that conservative causes that were laughed out of court for many decades can now prevail.

Federal courts, for example, have historically rejected claims by parents who seek to alter a public school’s lessons or curriculum because they object to it on religious grounds — largely due to concerns that it would be impossible for a school to tailor its lessons to align with the religious views of every single parent. Last term, however, in Mahmoud v. Taylor (2025), the Republican justices held that public schools must give parents advance notice of lessons that offend their religious beliefs, along with an opportunity to opt their child out of the lesson.

A final factor that contributes to the Court’s new fixation on culture war issues is that the Supreme Court often has to hand down decisions clarifying a new legal rule in the years after that rule is announced. This is especially true if the new rule is confusing or otherwise likely to spark disagreement among lower courts.

The justices in the Supreme Court’s current majority are, to put it mildly, less skilled at judicial craftsmanship than previous generations of justices. One example: The Republican justices’ decision in Bruen — which lays out their approach to Second Amendment cases — is so confounding that at least a dozen judges from both political parties have published opinions complaining that they cannot figure out how to apply it.

Bruen requires judges to ask if a modern-day gun law is “relevantly similar” to a gun regulation that existed centuries ago, and to strike down the modern-day law if it is not. But the justices who support Bruen have struggled to articulate just how similar the two laws must be, and lower court judges frequently disagree on how to apply Bruen to a particular case. That means that the Supreme Court will have to spend an unusual amount of its time resolving these disputes until Bruen is scrapped for a more workable standard.

All of which is a long way of saying that the Court’s new interest in cultural grievances was easy to predict after Barrett’s confirmation.

It is reasonably likely that, if Republicans maintain firm control of the Supreme Court in the future, that the Court’s fixation on cultural issues will end. Given enough time in power, Republican justices are likely to exhaust the list of precedents they wish to overrule and clarify many issues that currently confuse lower court judges. So culture war politics may fade from the Court’s docket as Republicans entrench their victories on these issues.

But, for the moment, at least, the six Republican justices appear quite eager to put their mark on US cultural politics. And they don’t appear likely to back away from these cultural grievances any time soon.

The post The culture war is consuming the Supreme Court appeared first on Vox.