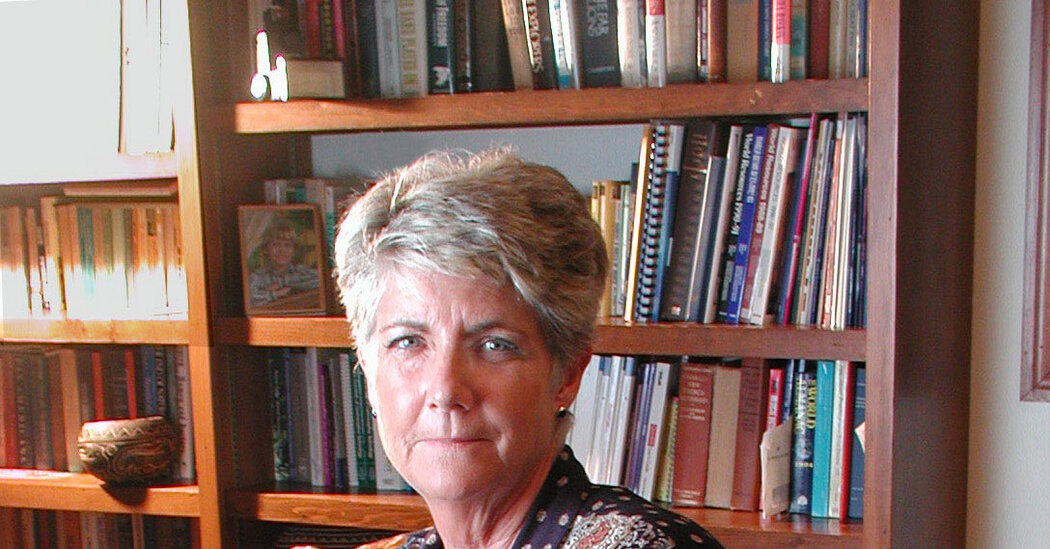

Sharon Camp, a public policy expert and advocate for women’s reproductive health who was known as the mother of Plan B, the emergency contraceptive pill, and who founded what was surely one of the world’s smallest pharmaceutical companies to bring it to market, died on Oct. 25 in La Plata, Md. She was 81.

Talcott Camp, a cousin, confirmed the death, in a rehabilitation facility, but did not specify a cause.

For nearly a half-century, doctors have known that women can prevent pregnancy within 72 hours of unprotected sex by taking a high dose of oral contraceptives. Initially, this remedy was not widely promoted; instead, it was used mostly in rape crisis centers in the United States and later in international refugee communities to help women who had been raped as an act of war, notably victims of sexual assault in the former Yugoslavia.

Dr. Camp, who had a Ph.D. in international relations,was a family-planning veteran. But for years she was only vaguely aware of emergency contraception, or the morning-after pill, as it is widely known.

A seasoned Capitol Hill lobbyist, she had come up during the 1970s, when family planning was a bipartisan issue. Even opponents of abortion were supportive, because effective contraception meant fewer abortions.

As vice president of the Population Crisis Committee (now Population Action International), a nonprofit focused on reproductive health care, particularly in developing nations, she had traveled throughout in Africa and had seen the consequences of poor reproductive care and lack of information in communities there. And like many women of her generation, she had firsthand experience: When she was 23, she had nearly died after having an illegal abortion in Mexico.

Following years of policy work, Dr. Camp was determined to get contraception directly into the hands of women and to make abortions safer. In the late 1980s, she and others founded the Reproductive Health Technologies Project, which worked to bring mifepristone, the so-called abortion pill, to the United States.

Then, Dr. Camp turned her attention to emergency contraception.

She studied its use in Europe, where it was not only legal but also mainstream, and learned of efforts to make it available in the United States. In California, clinics had come up with an expensive and complicated workaround: cutting up packets of birth control pills and repackaging them in sets of eight, the dosage required in most cases to prevent pregnancy during the first 72 hours after sex.

What was needed, Dr. Camp realized, was a simple pharmaceutical product. A Hungarian company was already making one and willing to partner with an American pharmaceutical company, but she was unable to find one that was interested.

In a 2003 oral history for Smith College in Massachusetts, she checked off the reasons: It was 1996, and anti-choice groups were becoming increasingly vocal; fringe groups were burning abortion clinics and shooting providers. Companies feared liability and boycotts, as well as threats, or worse, to their executives. Dr. Camp felt that the pharmaceutical industry, as she put it, “demonstrated the political instincts of celery.”

“Damn it,” she said, “if they won’t do it, we’ll do it ourselves.”

In January 1997, Dr. Camp founded Women’s Capital Corporation — initially, she said, it was a company of just three people, including herself — and began the daunting process for a business novice of figuring out how to get the drug packaged, marketed, distributed and, most important, approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

She knew she would need some deep-pocket investors, and she approached 150 venture capital firms. They all turned her down.

Then she approached donors from the reproductive health community, Planned Parenthood affiliates and other foundations, cobbling together their investments with grants and loans. Garnering them, she got to work.

A naming company was hired to come up with something to call the pill. Plan B, one of 25 suggestions, was the clear winner.

In one of many setbacks, the F.D.A. rejected the name, declaring that it “was unacceptable because it’s flippant and has a meaningless B suffix,” as Dr. Camp learned later, when she got hold of the agency’s naming committee minutes through a Freedom of Information Act request.

“But we knew this was the right name for this product,” she said, in no small part because it was easy to remember. “Given all the barriers to access,” she added, “it seemed very important to us that people could remember what to ask for.”

The twists and turns of how Plan B got to market, as Dr. Camp recounted in her oral history, played out like a thriller.

“It was a thriller,” said Francine Coeytaux, a veteran of the reproductive health movement who worked alongside Dr. Camp, “and Sharon was the author.”

In 1999, the drug and its name were proved by the F.D.A., but it stipulated that Plan B would be available only with a doctor’s prescription.

The next hurdle was approval for over-the-counter sales, Dr. Camp’s ultimate goal, which the drug received in 2006, though it was available only to women over the age of 18 (those 17 and under still needed a prescription), and only after pressure from Senators Hillary Clinton of New York and Patty Murray of Washington State, who had threatened to block the appointment of a new F.D.A. commissioner. A year earlier, Susan F. Wood, the director of the agency’s office of women’s health, had resigned to protest the delay.

“This is a way to prevent unwanted pregnancy and thereby prevent abortion,” Dr. Wood told The New York Times in 2005. “This should be something that we should all agree on.”

By then, she had moved on, wooed away by the Guttmacher Institute, a global research and policy organization focused on reproductive health, to become its president and chief executive. She had sold her company to Barr Pharmaceuticals in 2003; many company acquisitions later, the pill is now known as Plan B One-Step.

Plan B did not make Dr. Camp rich. Half of the proceeds went to the nonprofits that financed the product’s development; the rest went into a charitable trust. One beneficiary was Pomona College in California, Dr. Camp’s alma mater.

Sharon Lee Camp was born on Nov. 7, 1943, in Easton, Pa., the eldest of three daughters of June (Stout) and Albert Camp, a scientist who worked for the Navy. Part of her childhood was spent on a base in China Lake, Calif., where her father was developing rocket fuels.

She graduated from Pomona, where she majored in international relations, in 1965, and later earned a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in the same subject from Johns Hopkins University.

Dr. Camp’s first job after graduate school was as a lobbyist, working on food programs for children and Native Americans. She then joined the Population Crisis Committee, where she remained for nearly two decades.

She is survived by a sister, Cindy Lou Hampton.

Dr. Camp retired from the Guttmacher Institute in 2013, the same year, coincidently, that Plan B and generic versions of the drug were finally approved for over-the-counter use without age restrictions.

There continued to be challenges, as many on the right contended that the drug was an abortifacient — meaning that it caused the premature termination of a pregnancy. (It does not; it prevents conception, as regular birth control pills do.) The labeling was confusing, and it wasn’t until 2022 that the F.D.A. revised the enclosed leaflets to clarify that the medication acts before fertilization occurs.

Dr. Camp decried the growing polarization over women’s reproductive health issues that she had seen during her years in Washington; she had hoped that Plan B would bring the warring factions together.

“One of the things that has attracted me about emergency contraception from the beginning is that the pro-choice movement doesn’t really own it,” she said in 2003. “It’s the anti-abortion pill.”

Penelope Green is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk.

The post Sharon Camp, Mother of the ‘Plan B’ Contraceptive Pill, Dies at 83 appeared first on New York Times.