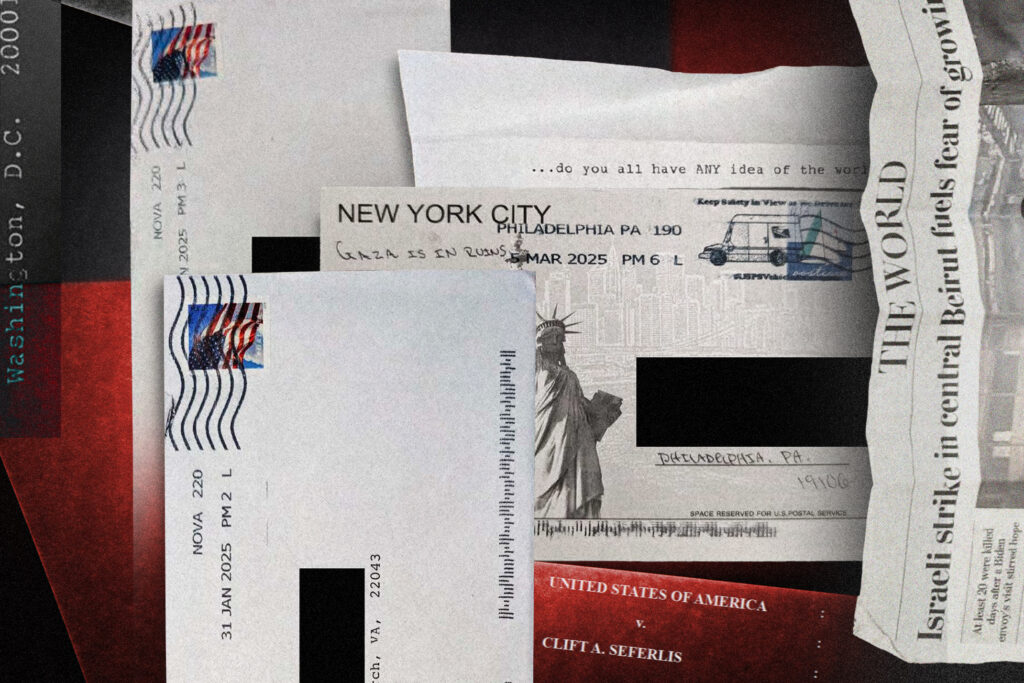

The first threat was handwritten on a postcard. The next was composed on a typewriter, then mailed to the same D.C. synagogue.

The threats felt eerily similar to a volunteer who helps protect Jewish institutions: unsigned, with a rambling cadence and enough detail to hint that whoever sent them had been outside the house of worship observing the mix of congregants and armed police officers standing guard.

The letters, the volunteer learned, were part of a pattern of dozens of mailed threats to Jewish institutions in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Virginia and Maryland as well as the District. Some mentioned people by name, including rabbis, and invoked recent and historical attacks against Jewish people in the United States and in Europe. Newspaper clippings on the Israel-Gaza war were often attached to the letters and postcards. At least three of the letters threatened damage to synagogues and recommended clergy make certain the buildings were fully insured.

Threats like these must be taken seriously, security experts, nonprofit leaders and community members said, when violence against Jewish people persists. On Dec. 14, a father and son killed at least 15 people and injured at least 40 in a shooting at an annual Hanukkah celebration in Australia, authorities said. Closer to home, a young couple who worked for the Israeli Embassy were killed in a shooting at the Capital Jewish Museum in D.C. in May.

Rabbi Mitchel Malkus, head of school at the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in Rockville, Maryland, where students participate in events each day of Hanukkah, reassured parents after the recent attack that the school places a priority on safety.

“We reflect on that at a time when we want to be proud of being Jewish and being comfortable practicing our religion,” he said.

Volunteers “don’t want to take any chances,” said Richard Priem, CEO of Community Security Service, a nonprofit that has trained thousands of Jewish congregants to protect over 500 synagogues and Jewish organizations across the United States. Since the shooting in Australia, Priem has been fielding calls from Jewish community leaders and others, requesting the help of volunteers as they gather for Hanukkah.

“We want to make sure that Jewish life can continue without threats,” he said.

When the mailings arrived at the D.C. synagogue in March 2024, the volunteer, who spoke to The Washington Post on the condition of anonymity out of concern about being individually targeted, reported the threats to the FBI and D.C. police. Then he notified colleagues and other Jewish organizations to be on the lookout.

Others, he soon realized, had noticed a pattern of threatening letters showing up in the mailboxes of synagogues and museums, schools and a deli — all of which were unnamed in documents filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Vera, another volunteer, who spoke on the condition that only her first name be used out of fears of being targeted, said the typewritten letter mailed to her Chevy Chase, Maryland, synagogue last July felt like another transgression in the onslaught of antisemitic attacks the area’s Jewish community was facing at the time.

Her synagogue had received bomb threats, she said. Others in the area, including her own, drew protesters who yelled at congregants as they walked in.

“In the last couple years, there’ve really been an uptick of various kinds of threats,” said Vera.

In 2024, there were nearly 500 more antisemitic incidents in the U.S. than the year before, according to the Anti-Defamation League, an anti-hate organization. These kinds of attacks, experts say, have become increasingly related to Israel or Zionism following Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023, attack against Israel that sparked a two-year war in the Middle East.

Since the 2018 mass killing at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Jewish institutions and synagogues across the nation have beefed up their security efforts, said Gil Preuss, CEO of the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington.

“Ten years ago, most synagogues didn’t have security people around every time that the building was open,” he said, reserving that for holidays or big events. Today, “they pretty much all do.”

In some places, that security can look like metal detectors or police or private security stationed at synagogue entrances. But the 6,000 trained volunteers who stand guard and monitor threats for Community Security Service put their safety into their own hands, Priem said.

New York-based CSS, like other community-oriented security groups, is part of a long history of Jewish people banding together to stand guard at Jewish institutions around the world, Priem said. There are similar organizations in cities like London, Paris and Sydney.

Jewish people “couldn’t always rely on governments to protect them,” said Priem, who is from Amsterdam and volunteered to protect his synagogue there when he was 17. “In my case, it was Dutch police officers who pulled my grandparents out of their home during World War II. It was not the Nazis.”

Jewish immigrants brought that security model to the United States, said Priem, which resulted in the founding of CSS in 2007. Since then, he said the group has reported more than 1,000 incidents and thwarted multiple attacks in major U.S. cities. In 2022, the New York Police Department arrested two men at Penn Station and seized an eight-inch military-style knife, a gun with a 30-round magazine, a ski mask and a swastika arm patch.

“That started with a volunteer flagging that it was a threatening Twitter post,” Priem said. The post suggested the two were headed to a synagogue in Manhattan.

“We want to prevent attacks, not respond to them,” Priem said.

After the letters began trickling in last year, the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington’s security arm, JShield, began hosting trainings on how to safely handle and store the mail as evidence for police, said Rusty Rosenthal, the federation’s executive director of regional security. Within months, the volunteer at the D.C. synagogue had connected with other volunteers and gathered more than a dozen letters that had been sent to various Jewish institutions in the region.

“What we highlighted for [the FBI] was the fact that [the letters] had spread across multiple field offices,” said the volunteer.

He would not know what would come of his efforts, he said, until he saw a Justice Department news release in June. A 55-year-old man had been arrested, following an investigation by FBI officials in Philadelphia and Baltimore, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, the Montgomery County Police Department and the U.S. attorney’s office for the District of Maryland.

For more than a year, according to court documents, Clift Seferlis of Garrett Park, Maryland, used the Postal Service to mail at least 40 threatening letters and postcards to more than 25 Jewish institutions.

When police obtained a search warrant for Seferlis’s home, the complaint says, they found a typewriter and cutout copies of The Post. He sent typewriter ribbons from Amazon to his husband’s house nearly 2½ miles away, prosecutors wrote. Phone records showed Seferlis was at the locations on or about the days when the letters and postcards were put in the mail.

On June 16, the day of his arrest, Seferlis admitted to an FBI special agent that he was the person behind the letters, the complaint says. At least seven ended up in the mail at a Jewish institution in Philadelphia where Seferlis had given tours, he said. He told the agent he was expected to return there three days later, according to the complaint.

“Seferlis knew that all of these mailings to Jewish institutions would be interpreted as threats to injure or kill the recipients,” prosecutors wrote in a court filing. He entered a guilty plea last month on 17 counts of mailing threatening communications and eight counts of obstruction of free exercise of religious beliefs. The amount of time he will serve under the plea agreement is unclear, but the 25 crimes Seferlis admitted to carry a maximum sentence of decades in prison and more than $5 million in fines. A sentencing hearing is scheduled for March.

The son of a celebrated D.C.-area sculptor and stone carver who designed flowers and gargoyles for Washington National Cathedral, Seferlis has taught workshops and done restoration work at the Smithsonian Castle and the Oak Hill Cemetery Chapel.

“He was a mainstream member of the community,” said the security volunteer at the D.C. synagogue. “It all goes to show you don’t know where these threats may come from.”

Protecting Jewish communities, said Priem, is empowering to CSS volunteers who see the work as “part of their Jewish experience.”

When Vera first started volunteering 14 years ago, she said the organization’s mission — “taking security into your own hands” — made her feel like she could play a role in keeping her community safe. After learning of Seferlis’s arrest, she said it felt good to know law enforcement took the reporting and observing done by volunteers seriously. But she doesn’t believe the threats will end.

The post He mailed dozens of antisemitic letters. Volunteers helped track him down. appeared first on Washington Post.