A group of Black Maryland state lawmakers plan to propose a bill during the upcoming legislative session that would create an independent commission to investigate the deaths of hundreds of Black children who died at a segregated juvenile detention facility during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Members of the General Assembly’s Legislative Black Caucus are drafting a bill that would create the investigative body and allocate $750,000 so the commission can assemble a full accounting of what happened at the House of Reformation and Instruction for Colored Children — where Black boys as young as 7 were committed, typically for minor offenses.

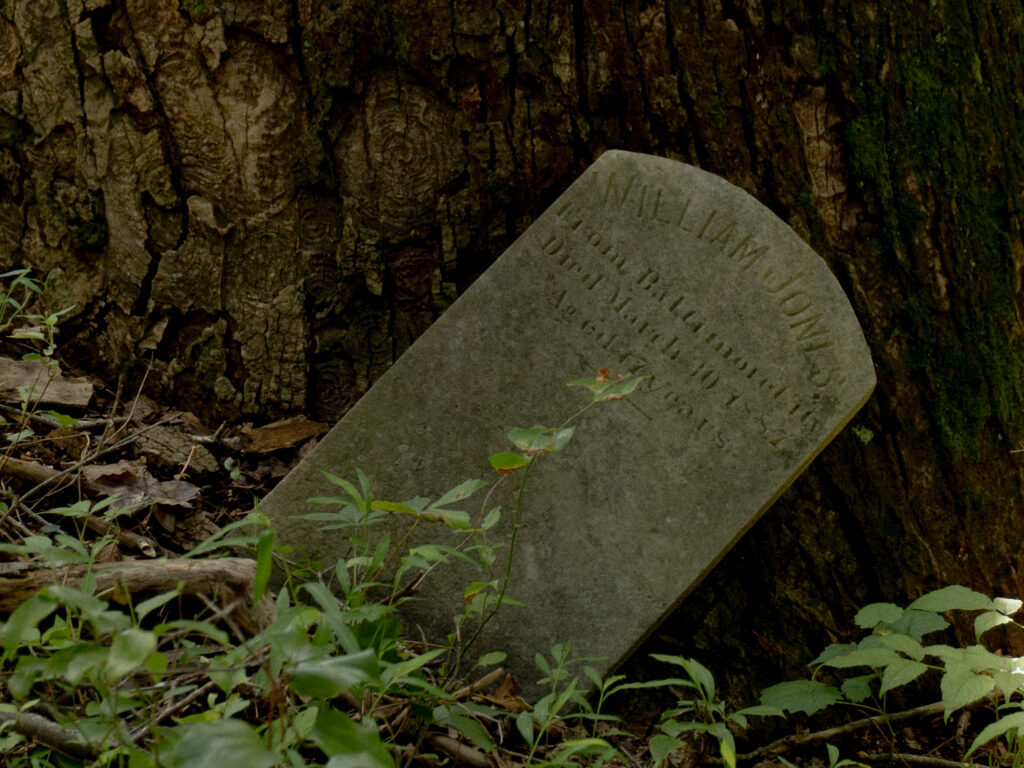

Boys who died at the facility were buried on state-owned land in Cheltenham, near the former House of Reformation. State Sen. William C. Smith Jr. (D-Montgomery) and lawmakers who represent the area in Prince George’s County where the grave site is located, including Del. Jeffrie E. Long Jr. (D-Calvert) and state Sen. Kevin M. Harris (D-Prince George’s), said they will file the bill at the beginning of the legislative session in January.

The third-party nature of the commission is essential, Smith said, “because no agency and no entity can investigate itself.”

“The independent investigation will do a very thorough analysis and inquiry into some things that will ultimately and undoubtedly be uncomfortable to learn,” Smith said. “And to have that information presented in an unbiased and unvarnished manner is critical to the purpose of this project, which is to provide Marylanders an explanation and understanding of the tragedies that happened here.”

Long, who will sponsor the bill in the House of Delegates, said that since learning about the graveyard earlier this year, he has wanted to make it his “mission” to ensure the House of Reformation boys are properly memorialized.

“A graveyard is filled with a bunch of potential,” Long said about the lost lives there. “And we have so much potential, so many people that could have been history makers, agents of change, barrier breakers. That were thrown into horrible conditions and treated, really, as three-fifths of a man and then buried, covered up and forgotten about.”

“It could have been me,” he said. “I see myself in them because it could have been any one of us.”

A Washington Post investigation in September found that for decades, Maryland officials allowed the boys’ unmarked graves to remain dilapidated, even as they approved construction of a well-kept veteran’s cemetery yards away. The reporting also found that at least 230 children died at the facility between 1870 and 1939, far exceeding the 67 previously estimated by the state.

Staff members of Maryland’s Department of Juvenile Services rediscovered about 100 of the graves last year, finding them in an overgrown, wooded patch of state property — many marked only by cinder blocks. Without further forensic and anthropological work at the site, it’s impossible to determine exactly how many children are buried in the House of Reformation graveyard.

Earlier this year, the Department of Juvenile Services applied for $31,000 in grant funding from the state to begin restoration efforts. Gov. Wes Moore (D) also pledged to allocate funds in next year’s state budget. Georgetown University has hired the department’s former deputy secretary, Marc Schindler, to lead a team of researchers working to identify those who died and locate potential living family members.

If established, the independent body would also be empowered to work in concert with other organizations and academic institutions, which could include Georgetown’s research hub. The commission would be led by an experienced investigator authorized to appoint up to two deputies with relevant juvenile-justice expertise, lawmakers said.

“The condition of this burial ground represents a profound and long-standing failure of the State to provide dignity in death to children for whom it had assumed responsibility in life,” lawmakers wrote in a draft version of the bill shared with The Post. “The State of Maryland has a moral and civic duty to the deceased, their families and all its citizens to uncover the full truth of what occurred.”

Harris, a U.S. Navy veteran, said he was struck by the juxtaposition of the dilapidated, overgrown House of Reformation cemetery and the meticulously maintained Cheltenham Veterans Cemetery right beside it when he and other Black Caucus members visited the site in the fall.

During the trip, the lawmakers prayed near the graves, vowing to take action.

“We need to bring some sense of dignity back to that area,” Harris said. “I think the community needs healing. This initiative isn’t just about honoring and uncovering the past — it’s about healing the communities affected by these historic tragedies.”

If approved by the General Assembly, the bill would task investigators with providing a “complete public accounting” of the children who died while in the House of Reformation’s care and were buried on its grounds, including cause of death. While the House of Reformation was still open, child welfare advocates and concerned parents alleged that those detained at the facility faced abuse, neglect and mistreatment.

Under the proposal, findings and recommendations would be due back to lawmakers by Dec. 30, 2028.

Investigators would be permitted to use archaeological tools, including ground-penetrating radar, to locate and map unmarked graves at the House of Reformation and determine how many individuals are buried there. Where necessary, and in consultation with descendants, the bill also allows the commission to exhume and analyze remains to determine biographical details about the boys and look for signs of trauma or neglect.

Any evidence of criminal conduct uncovered by the investigation would be referred to the attorney general or an appropriate state prosecutor, the draft bill says.

DNA samples collected from the exhumed graves would be used to build a database to help find potential descendants, an effort supplemented by a review of state documents and archival records.

After completing the archaeological work, the commission would make recommendations to establish a permanent public memorial and create a process to repatriate identifiable remains, while reburying unidentified remains in a dignified manner.

The legislation also calls for the creation of educational initiatives to incorporate the House of Reformation’s history into the state curriculum.

The post Md. lawmakers seek probe into Black boys buried in abandoned graveyard appeared first on Washington Post.