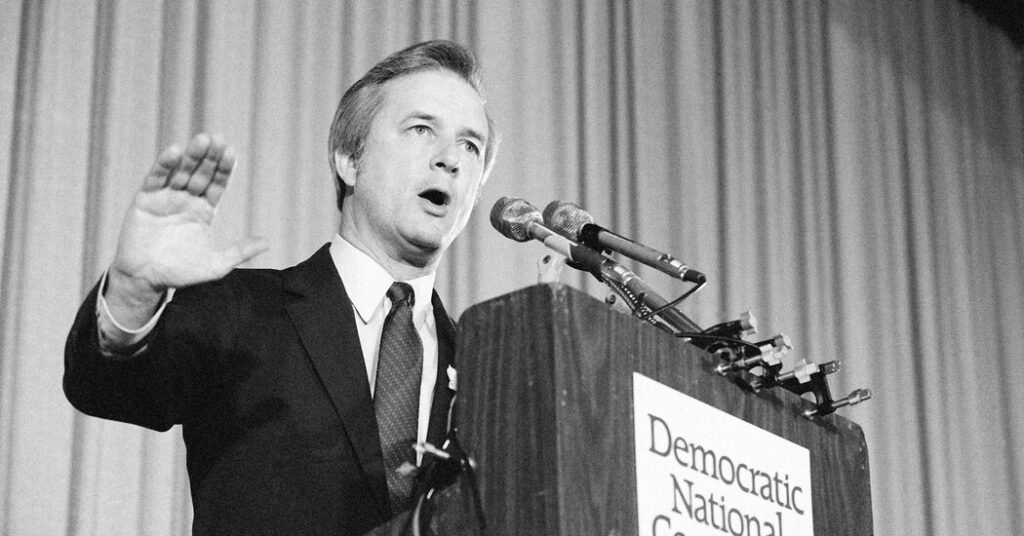

James B. Hunt Jr., who burnished North Carolina’s reputation as a beacon of moderation in the South over four terms as governor but lost the Senate race that could have vaulted him to the presidency, died on Thursday at his home in Lucama, N.C. He was 88.

His daughter Rachel Hunt, North Carolina’s lieutenant governor, announced the death in a statement, but did not cite a cause.

With his moderate-to-liberal brand of politics and formidable statewide organization, Mr. Hunt sustained the Democratic Party as a political force in North Carolina for more than a quarter century. Winning elections — even as Republicans like Richard M. Nixon and Robert J. Dole captured the state’s presidential votes — he held back the partisan realignment that transformed the rest of the region beginning in the 1970s.

Mr. Hunt’s formula for success mirrored that of the North Carolina Democrats who preceded him, as well as those who have kept the state politically competitive since he retired: a zealous focus on public schools and state colleges, a friendly attitude toward business and a nose for the middle ground on contentious issues of race and culture. But he distinguished himself beyond the state’s borders with his record-setting longevity, relentless drive and record of achievement.

In his 16 years as governor — he served a pair of terms from 1977 to 1985, and two more from 1993 to 2001 — Mr. Hunt gained national acclaim for his commitment to education. He raised teachers’ salaries; became a mentor for at-risk youth and encouraged others to do the same; started North Carolina’s Smart Start preschool program; and created a state science and math high school.

He was equally consumed with modernizing his state’s economic base. And he grasped the link between those two priorities, recognizing that his focus on education, and the publicity it garnered, would make it easier to attract businesses to the state, to supplement the long-dominant tobacco, textiles and furniture industries.

In a state with a history of cosmopolitan liberalism and an equally enduring tradition of Christian fundamentalism, Mr. Hunt was able to appeal to North Carolinians of all stripes.

He was the teetotalist son of a farmer who grew up attending a primitive Baptist Church. But he was also the son of New Deal Democrats.

“Hunt grew up in a world where conservative values and liberal politics melded together,” Rob Christensen, a longtime North Carolina political reporter, wrote in his 2008 book, “The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics.”

First elected as lieutenant governor in 1972 — a year in which George McGovern won less than 29 percent of the vote in North Carolina during the presidential election — he was one of the few Southern Democrats who found success in an era of conservative backlash. When Mr. Hunt won the governorship for the first time in 1976, Jimmy Carter was easily claiming North Carolina, but it would be the last time in any of Mr. Hunt’s statewide campaigns that a Democratic presidential nominee carried the state.

None of those top-of-the-ticket defeats proved more debilitating to Mr. Hunt than the one in 1984.

It is the great and — to a generation of liberals in North Carolina and beyond — tragic irony of Mr. Hunt’s career that despite his record of success, his most memorable campaign was his lone defeat.

The Senate race between Mr. Hunt and Senator Jesse Helms, Republican of North Carolina, the incumbent, was billed as a clash of political titans — the New South against the New Right — and it equaled the hype: It was ugly, expensive and enormously consequential.

The campaign was a test of clout between the growing force of Black voters in the South, whose numbers had swelled thanks to the registration efforts of the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who was running for president, and the equally ascendant ranks of Christian conservatives. It was also a measure of the popularity of Ronald Reagan, the incumbent president, and his ability to lift Republicans in the region at a time when there were still far more registered Democrats.

For Democrats across the country, the 1984 race was a chance to end the career of a conservative who was as much a bête noire as Mr. Reagan — and, in their eyes, represented the worst of the South’s intolerance on issues of race, gender and sexuality.

Mr. Helms, who called African American voters “the bloc vote,” assailed Mr. Hunt on race. In an advertising onslaught and during four debates, the senator attacked the governor for supporting the newly enacted holiday honoring the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., which Mr. Helms had vociferously opposed, and for his support of the Voting Rights Act. He also repeatedly linked Mr. Hunt to Mr. Jackson in pamphlets and advertisements.

“Which is more important to you, Governor: getting yourself elected with that enormous bloc vote or protecting the Constitution and the people of North Carolina?” Mr. Helms asked Mr. Hunt during one debate.

Mr. Hunt shot back: “Jesse, which is most important to you: Getting re-elected or having the people of this state be upset and fighting and set at odds against each other? My gracious, how far back do you want to take us? Twenty, 30, 50 years?”

The back-and-forth between the candidates ultimately mattered less than the race at the top of the ticket. Mr. Helms aggressively tied himself to Mr. Reagan and linked Mr. Hunt to Walter F. Mondale, the Democratic presidential nominee, by mentioning Mr. Mondale’s name dozens of times during their final debate.

The president routed Mr. Mondale in North Carolina and swept Mr. Helms to re-election: Mr. Reagan won North Carolina by 24 points, while Mr. Helms defeated Mr. Hunt by four points.

The two candidates spent more than $25 million, making it the most expensive Senate race in history at the time. It was a bracing reality check for Mr. Hunt and others in the state who clung to the view that North Carolina was exceptional in the South.

The loss, which came at the end of Mr. Hunt’s second term as governor, seemed to extinguish his political ambitions.

Three years later, he told David S. Broder, a columnist for The Washington Post, that if he were in the Senate, he would probably be running for president.

Mr. Hunt, Mr. Broder wrote in a column titled “If Only He’d Beaten Jesse Helms,” “is so close to the Democratic ideal for 1988 that he would surely be one of the favorites at this point.”

James Baxter Hunt Jr. was born in Greensboro, N.C., on May 16, 1937. His mother was a teacher and his father farmed and worked as a federal soil conservation agent.

After graduating from North Carolina State University, Mr. Hunt earned a law degree at the University of North Carolina. When he was elected as lieutenant governor in 1972, he became one of the few statewide Democrats remaining after Mr. Nixon’s landslide that year.

He easily won his first bid for governor four years later, just as he did the next three times he ran for the office.

After his defeat by Mr. Helms, Mr. Hunt joined a prominent law firm in Raleigh, N.C., where he worked for corporate clients. He declined a rematch with his Republican opponent in 1990. But two years later, he reclaimed the governorship, holding that office longer than any North Carolinian in history.

Alan Blinder and Hannah Ziegler contributed reporting.

Jonathan Martin is a senior political correspondent for The Times, a political analyst for CNN and the co-author of “This Will Not Pass: Trump, Biden and the Battle for America’s Future.”

The post James B. Hunt Jr., N.C. Governor Who Kept State Blue, Dies at 88 appeared first on New York Times.