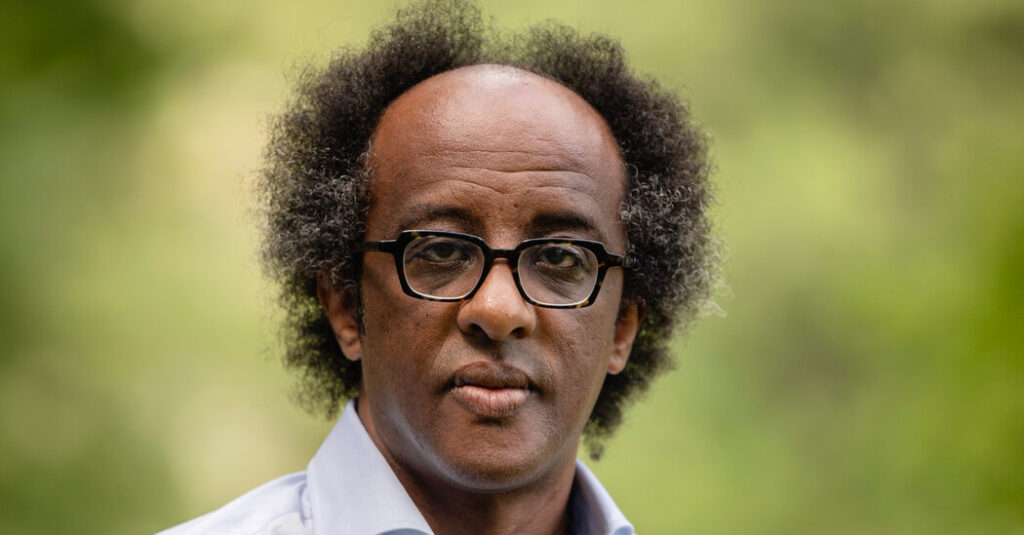

The novelist Dinaw Mengestu was elected president of PEN America on Wednesday, taking the helm as the organization navigates rising challenges to free speech across the country along with continuing fallout from criticism of its own response to the war in Gaza.

Mengestu, 47, was born in Ethiopia and moved to the United States when he was 2. In his four novels, including “Someone Like Us,” published last year, he frequently explores the lives of migrants whose inner and outer lives unfold in multiple places.

PEN America, founded in 1922, is a similarly boundary-crossing organization. Long known for its stalwart defense of imprisoned writers abroad, it has expanded its domestic focus in recent years, becoming a leading voice against book bans and state laws restricting teaching on race, gender and sexuality.

Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in October 2023, the group has also been roiled with conflict over what some criticized as a failure to adequately respond to threats to writers in Gaza. In 2024, its literary awards and annual World Voices Festival were canceled after many writers withdrew, and its longtime chief executive, Suzanne Nossel, departed. (Both events resumed in 2025, and a search for a new chief executive continues.)

In an interview, Mengestu, who leads the Center for Ethics and Writing at Bard College, talked about the evolving role of PEN America, whose past presidents have included Ayad Akhtar, Jennifer Egan, Salman Rushdie and, most recently, Jennifer Finney Boylan. The following excerpts have been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’ve been on PEN America’s board for nearly a decade. Before that, what was your image of the group?

As an aspiring writer, my idea was that it was very much this elite little club, where if you’d published a certain number of books, of a certain caliber, you’d get invited to sit at the banquet table. But my vision was limited to an older version of what PEN America did, and even that wasn’t accurate. There’s always been a history of political and global activism.

In a recent essay, you wrote that PEN America’s defense of free expression is “not rooted in law but in literature and in the singular voice of writers who make it.” What do you mean?

Many groups advocate for free speech. But it’s the relationship between free expression and literature and writers that makes PEN America’s work so unique. If we lose awareness of how important our culture of literary and artistic production is, our understanding of free expression goes with it. If all those are eroded or devalued, you don’t have to worry about banning any books. They will be so marginal to society they no longer have value.

Has the task of defending free expression changed in the second Trump administration?

Earlier this year, we had a report on all the words that the Trump administration has been trying to erase. That’s one way of calling attention to what is happening. Many voices in the country are unable to speak, afraid to speak. If you want to speak about trans rights, about Palestinian rights — those are really difficult things to talk about if you are in any way vulnerable, say, if you’re an immigrant. But there are some kinds of silencing that aren’t that easy to fight through the courts.

In September, PEN America issued a report detailing what it called the “catastrophic destruction of Gaza’s cultural heritage,” which amounted to “war crimes and crimes against humanity.” Do you agree with critics who said the group did not do enough initially to help Palestinian writers?

I don’t want to back away from positions in past. But with the question of whether we were doing enough, it was very fair for writers to say no and ask us to do more. Writers are the ones who hold us accountable. Since then, we have done more than ever to actually get support to the community of writers that were impacted.

Can you be more concrete about that support?

We agreed with partner organizations that we would work with the utmost discretion. I can say that we have worked to help relocate Palestinian writers and artists to other countries. For those with no way of remaining in Gaza, we were able to work to help them rebuild new lives.

Do you worry the controversy did lasting reputational damage to PEN America?

It’s important we not just try to mend and rebuild, but also find a way to connect with writers and make them feel like they have a real stake, that they are not just figureheads.

What will be your priorities as president?

We really need to have an active literary presence on the board. It’s important that the free expression work is loud and at the forefront, and that it’s happening in partnership with the literary community. We also need to deepen our relationships with PEN International chapters. There’s a strong antidemocratic stream moving throughout the world. If there’s a moment when we can’t become a purely internal organization, it’s now.

Jennifer Schuessler is a reporter for the Culture section of The Times who covers intellectual life and the world of ideas.

The post PEN America Elects New President at Fraught Time for Free Speech appeared first on New York Times.