“I like to look at what everyone is doing, find some common thing that they’re all assuming implicitly,” Rodney Brooks said, “and negate that thing.”

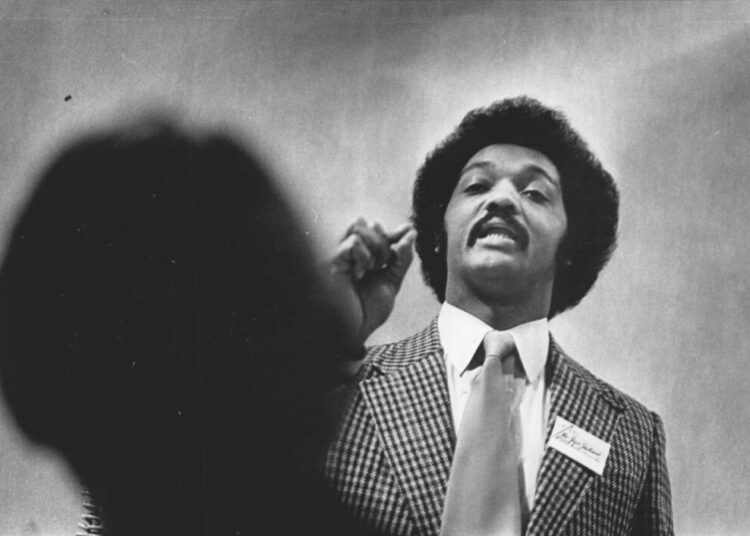

The pioneering roboticist was speaking directly to camera in the 1997 Errol Morris film “Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control,” which juxtaposes interviews of Mr. Brooks, a lion tamer, a topiary gardener and a researcher who studies naked mole rats. “Four men,” Mr. Brooks said recently, “who were each trying to control nature in their individual way, and all of us were failing.”

In the film, Mr. Brooks was describing an early breakthrough. In the 1980s, limitations on computing constrained robot development. Watching insects, he realized they possessed little brainpower but were far more capable than his robots, and that mimicking animal biology was smarter than trying to control every aspect of a robot’s behavior through code. His successes led him to predict robots “everywhere in our world.”

At 70, the former M.I.T. lab director and co-creator of the widely-selling Roomba robot vacuum lives in that world. But now, Mr. Brooks, who has spent his career making intelligent machines a part of everyday life, finds himself playing the skeptic.

Today’s entrepreneurs promise robots that not only look human — or human-ish — but can do everything a person can.

Tech investors are pouring billions into the effort, but Mr. Brooks argues that general-purpose humanoid robots will not be coming home soon, and that they are not safe enough to be around humans. In September, he delivered an authoritative takedown in an essay that concluded that over the next fifteen years, “a lot of money will have disappeared, spent on trying to squeeze performance, any performance, from today’s humanoid robots. But those robots will be long gone and mostly conveniently forgotten.”

His blog post kicked off a furor in the small world of robotics. This was a legend in the field, whose insights had informed the humanoid craze. “At least a dozen people asked me if I agreed with it shortly after it went live (I don’t),” wrote Chris Paxton, a researcher in artificial intelligence and robotics who tracks the rapidly developing discipline.

Mr. Brooks remembers the German technologist Ernst Dickmanns’ self-driving car, which began motoring across Europe in 1987. He was around when IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer defeated the chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997, and when A.I. researcher Geoff Hinton predicted in 2016 that radiology would be obsolete in five years because machine learning software can do it better.

All of these were important developments, but drivers, chess players and radiologists are still among us.

Mr. Brooks insists he is simply being practical. “We’re going to go through a big hype, and then there’s going to be a trough of disappointment,” he said in an interview.

The Humanoid Arms Race

The physical appearance of a robot, Mr. Brooks likes to say, makes a promise about what it can do. Robots in wide use today are designed for specific jobs in specific situations, and look like it — an arm that does the same repetitive action on a manufacturing line, or the automated pallet movers in Amazon warehouses. They aren’t flashy.

“People see the humanoid form,” Mr. Brooks said, “and they think it’s going to be able to do everything a human can.”

In other words, humanoid robots are the perfect idea for Silicon Valley, where above all, the potential for growth is everything to a venture-backed company. The market for what a human can do is the biggest market of all.

That is why Elon Musk’s Tesla appears to be betting the company on its robot, Optimus. In October, Musk said building such robots at scale is “the infinite money glitch,” and he predicted that his company’s robot “could probably achieve 5x the productivity of a person per year because it can operate 24/7.” He thinks, among other things, that Optimus will be an excellent surgeon, a bold claim, since human-level dexterity is among most difficult challenges in robotics

Mr. Musk is not the only one with big aims. Among others, the start-up Figure AI has raised almost $2 billion since 2022 to develop its line of C-3PO-style bots for everything from manufacturing to elder care. You can spend $20,000 to get a robot built by Palo Alto’s 1X Technologies in your house next year — but its limited autonomy will be supplemented by the company’s employees, who will control it remotely in a scheme to teach it new tasks.

This is only the latest run at what Mr. Brooks and his co-authors referred to as the “Holy Grail” in a 1999 paper. Past attempts at building general-purpose humanoid robots stalled out at the complexity of walking on two feet, and other such difficulties of mimicking the human form with electronics.

Then there’s the sheer number of situations that humans can find themselves in. How do you write the code that, to solve one commonly cited bit of outsourceable drudgery, gets the robot around each weird and particular home, collects the laundry, separates the loads, and cleans the lint trap?

The wave of generative A.I. provides a new answer: teach the robot to do it the same way we teach computers to recognize people, transcribe audio recordings, or respond to prompts like “write a ’90s rap song about my dog Miso.”

Training neural networks with lots of data is a proven technique, and there is already lots of data of humans moving around their environment — decades of footage of people doing stuff to feed into the data centers.

The results can seem impressive, at least on video, where humanoid robots from Figure and other companies can be seen folding laundry, putting away toys, even sorting components in a South Carolina BMW factory.

What you don’t see in most of these videos is people standing near the robots. Mr. Brooks says he wouldn’t get within three feet of a humanoid bot. If — when, he says — they lose their balance, the powerful mechanics that make them useful make them dangerous.

Safety regulations generally require people to keep away from robots in industrial settings. Aaron Prather, the director of robotics and autonomous systems at ASTM International, a standards-setting organization, said that humanoid bots aren’t inherently unsafe, but require clear guidelines, particularly as they leave settings where people are trained to work alongside them.

“For robots entering homes, especially teleoperated humanoids, we’re in new territory,” Mr. Prather said.

In November, Figure’s former head of product safety filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against the company, claiming he was fired after trying to adopt stringent safety guidelines. Figure declined to discuss its technology, but a representative denied the allegations in the lawsuit, saying the employee was terminated for poor performance. A representative for 1X said that its in-home robot relies on new mechanisms that “make NEO uniquely safe and compliant around people.”

The Manufacturing Problem

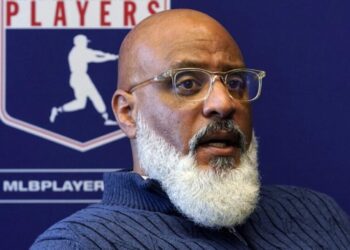

In some sense, Mr. Brooks has only himself to blame. The current humanoid craze is “kind of his fault,” said Anthony Jules, Mr. Brooks’s co-founder and C.E.O. at Robust.AI, which is building automated carts to work alongside humans in distribution centers.

Mr. Jules was an M.I.T. undergrad in the 1990s when Mr. Brooks was leading the school’s Computer Science and A.I. Laboratory — helping create the algorithms behind today’s autonomous cars, pioneering the feedback loops that link A.I. and robotics, and making the case that robots in human form are worth building.

Mr. Brooks, who grew up in Australia, arrived at Adelaide’s Flinders University in 1972 at the same time as academic refugees fleeing the end of the Prague Spring, allowing him to receive a “classical Eastern European mathematics education.” More important, he was able to spend 12 hours each Sunday futzing around with the university’s only mainframe computer.

He co-founded his first A.I. start-up in 1984 while a professor at Stanford, writing code at home on a Sun Microsystems workstation and FedEx-ing memory tape to Silicon Valley each morning.

After his insect inspiration that same decade, Mr. Brooks built robots that learned to move on their own, and co-founded the company that would become iRobot in 1990. By 1993, he and his graduate students set to work on a humanoid robot at a time when few researchers thought that would be a useful path of exploration.

Cog, as it was called, was designed to push the limits of robotics and, in particular, to apply insights from cognitive science about the links between intelligence and sensory perception.

Humans depend on physical context, sensation and multiple internal “control systems,” and Cog would learn from the world around it, rather than from coded instructions.

Still, even by the turn of the century, humanoid robots were unready for commercialization.

Mr. Brooks had learned hard lessons fighting over pennies in the Roomba’s manufacturing budget in the late ’90s. When Aaron Edsinger, a graduate student working on humanoid robots, later asked Mr. Brooks for tips about building his own company, the professor suggested his student imagine shipping a robot as a sheet of graph paper. “Your dissertation there? You just colored in one square. You have all that other work to do, which is not the research. It’s deployment, reliability, manufacturing, all that stuff, right?” Mr. Edsinger recalled.

The Roomba, after all, which defined the consumer robotics category, was eventually supplanted by Chinese models that rely on laser sensors instead of optical cameras. (Mr. Brooks left the company in 2008.) Engineering beat out innovation.

Eventually, Mr. Brooks did take on humanoids, co-founding the company ReThink Robotics in 2008. It developed two robots, Baxter and Sawyer, designed to do industrial work but safe enough for humans to work alongside. (They had a head, torso and arms, but didn’t walk.)

Though popular with researchers, the company didn’t gain traction, according to industry observers, because the safety mechanics limited the robot’s precision; Mr. Brooks argues the design was too different from what robot buyers were used to.

A Realist, Not a Pessimist

Mr. Brooks is particularly skeptical that neural networks are ready to solve the dexterity problem. Humans don’t have a language for gathering, storing and communicating data about touch, the way we do for language and imagery. Our fingers’ remarkable sensing ability collects all kinds of information that we can’t easily translate for machines. In his view, the visual data preferred by the new guard of robot start-ups simply won’t be able to recreate what we can do with our fingers.

“My students have built lots of hands, my students have built lots of arms, shipped tens of thousands of robot arms,” Mr. Brooks said. “I’m very convinced that humanoid robots are not going to have human-level manipulation.”

Researchers argue that if visual data alone isn’t enough, they can add tactile sensors to their robots, or use internal data collected by the robot when it is operated by a remote human user. It’s not clear if those techniques will be cheap enough to make these businesses sustainable.

But there are also many outcomes between human nimbleness and a failed robot.

“Rod makes a lot of great points, but one that I disagree with is that we need to achieve human-level dexterity to get value out of general-purpose robots,” Pras Velagapudi, the chief technology officer of Agility Robotics, said.

Mr. Brooks would say he is a realist, not a pessimist. His main worry is that too much focus on the trendiest training techniques will leave other promising ideas neglected. He does expect robots to work alongside people in the decades ahead, and that we may even refer to them as humanoid — but they will be on wheels, he says, and have multiple arms, and probably won’t be general purpose.

He currently works at a battered armchair perched above the mock-up warehouse in San Carlos, Calif., where Robust’s robots learn their trade, but he expects to step away from corporate life in the next few years. Not for retirement, but to write a book about the nature of intelligence, and why humans won’t create it artificially for another 300 years.

“It’s been my whole life,” Mr. Brooks says of the ever-expanding dream of A.I. “What I hate now is artificial general intelligence. We were always working toward artificial general intelligence!” he said, “and soon they’ll be calling it artificial superintelligence.”

“I don’t know what’s going to come after, it’s going to be artificial hyperintelligence.”

The post He’s the Godfather of Modern Robotics. He Says the Field Has Lost Its Way. appeared first on New York Times.