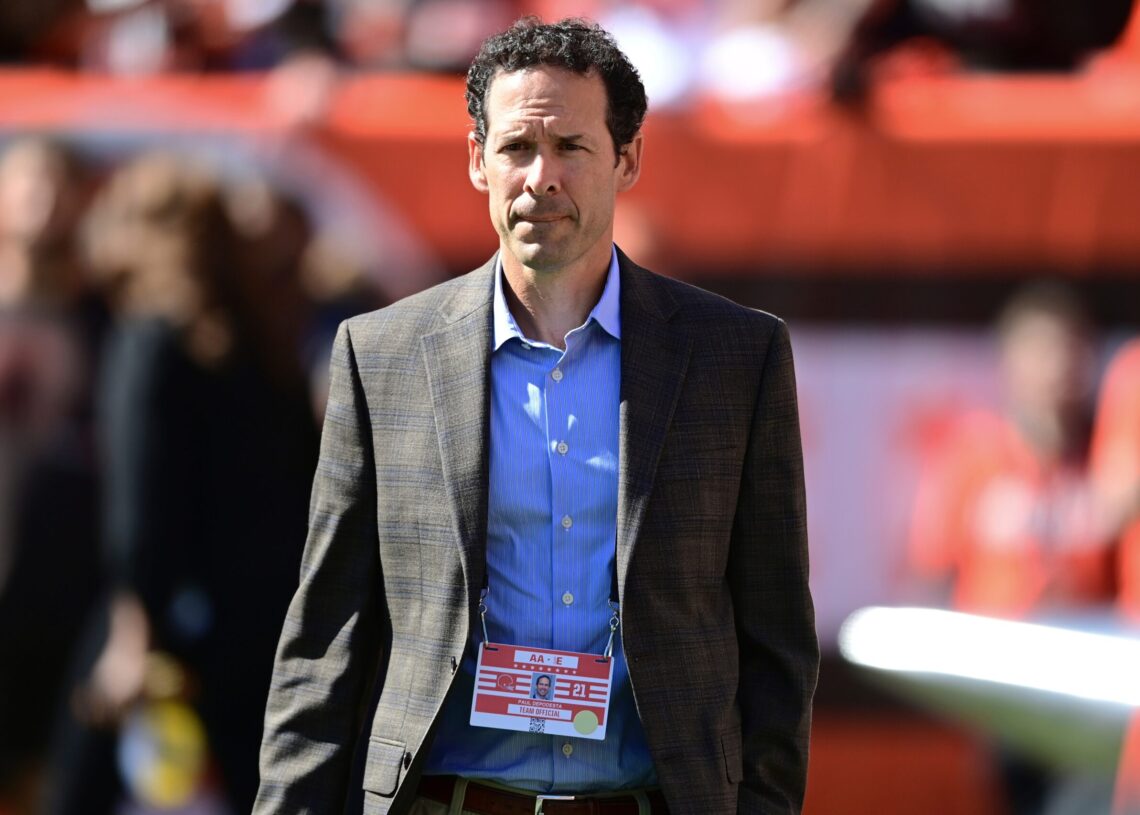

LAS VEGAS — Before the start of business at MLB’s general managers meetings Tuesday morning, in one of the labyrinthian halls of the Cosmopolitan’s conference center, Paul DePodesta walked back into his old fraternity. He chatted comfortably with San Diego Padres executive A.J. Preller as they strolled toward morning coffee with the other teams’ heads of baseball operations, as if they had both been there all along.

LAS VEGAS — Before the start of business at MLB’s general managers meetings Tuesday morning, in one of the labyrinthian halls of the Cosmopolitan’s conference center, Paul DePodesta walked back into his old fraternity. He chatted comfortably with San Diego Padres executive A.J. Preller as they strolled toward morning coffee with the other teams’ heads of baseball operations, as if they had both been there all along.

But DePodesta hasn’t been here since he was hired as chief strategy officer of the NFL’s Cleveland Browns in 2016, though he used to be quite a fixture. He hasn’t run a front office since being fired by the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2005, though he was a high-level baseball executive for 20 years, most recently for Sandy Alderson’s New York Mets. He was a wunderkind who became a Sabermetrics poster child after the book and subsequent movie “Moneyball,” which elevated his legacy as the numbers savant behind the heyday of the stingy-but-successful Oakland Athletics and earned him a job as head of Dodgers baseball operations at just 31.

He was, in other words, the front-office man of a famous baseball moment, like Theo Epstein with the curse-breaking Boston Red Sox, like the Tampa Bay Rays-generated savants of more recent years. But when he took the job with the Browns, the industry understanding was that he had conquered baseball, at least to his satisfaction, and had left a rapidly changing game behind.

So when he was announced last week as the Colorado Rockies’ new president of baseball operations, the news was something close to jaw-dropping. The Rockies job was the talk of front-office types throughout the postseason, a source of intrigue because of the sense that building a reliable winner in the high altitude at Coors Field is this sport’s most glaring unsolved riddle.

Now DePodesta, who has been out of baseball for 10 of the most transformative years in the game’s history, becomes the latest man to try to solve it.

“I’m very open to experimenting and trying different things. I’ve said this before: I don’t have all the answers by any stretch. I’m pretty relentless in trying to find them,” DePodesta, 52, said to a larger crowd of reporters than typically surrounds the Rockies’ head of baseball operations at these proceedings. “I think we’ll probably be experimental, too. We have to be willing to try different things.”

DePodesta proved his willingness to experiment, at least with his own career, when he left MLB for that Browns job nearly 10 years ago. He said he couldn’t pass up the challenge, and that he wanted a chance to learn and grow.

“I thought if I didn’t do it,” DePodesta said, “I would always regret it.”

In the early years of his sabbatical, he said, teams did come calling, hoping he would return. He said none of those opportunities were compelling enough to pull him away from his project in Cleveland when he was still building there, and that by the time his Browns venture stalled in recent years, the baseball calls had largely stopped.

The Browns were 56-99-1 during his tenure, a .362 winning percentage that was fourth lowest in the NFL during that time. And his résumé was not spotless in terms of culture-building, either: DePodesta was part of the Browns’ leadership circle when they made the polarizing deal in 2022 to trade three first-round draft picks for talented but troubled quarterback Deshaun Watson, who was facing multiple lawsuits for sexual misconduct at the time. Watson has mostly been injured and made little on-field impact since the deal. Somewhat fittingly, Browns owner Jimmy Haslam has since referred to the trade as “a swing and a miss.”

“A lot of decisions, really most of your decisions when it comes to significant player decisions — whether it’s the draft, free agent, trade, whatever — I consider those to be organizational decisions,” DePodesta said. “So really anyone who is in the senior leadership group, we all own those decisions, every one of them. That’s how I feel about that one; that’s how I feel about all the other ones.

“I would just say there’s a lot we can’t share publicly, but there was an incredible amount of diligence that goes into every one of our decisions in the course of the last 10 years.”

With that deal and yet another losing NFL season looming over DePodesta in Cleveland, his name did not exactly pop up regularly when MLB teams were looking for front-office makeovers. It wasn’t until what he called a “mutual third party” connected him with the Rockies that he again had a baseball job to consider.

And the particular baseball job that came his way offered a challenge as complex as the résumé of the man being pursued to meet it: Rockies owner Dick Monfort has tried to find someone capable of building a sustainable winner in Denver for years, but his lack of spending on baseball infrastructure and tendency to meddle in the plans of his potential saviors left the Rockies with a reputation as the most haphazard, backward and analytically challenged organization in the game. They have finished last in the National League West for four straight seasons and have finished well below .500 in the past seven. They have not played in a postseason game since 2018 and have not won one since 2009.

As such, DePodesta admitted he was “curious” what kind of autonomy Monfort planned to give his next head of baseball operations when he first discussed the job. But he said he found an ownership group eager to tap into his experience building out a data department in the NFL, as well as his data-driven baseball history.

“Typically when these jobs become available, it’s because there’s a desire for change. And usually a need, but certainly a desire,” DePodesta said. “I figured that was the case here, but I was curious to see how they felt about it. And I think they were very interested by the idea of bringing in some different perspectives and different ways of doing things.”

The main problem for the Rockies over the years, amplified by Monfort’s sometimes puzzling personnel choices, is pitching. No Rockies regime has fully solved Coors Field’s knack for turning good breaking balls into less good breaking balls and turning singles into doubles, a problem that stretches back generations and deters top free agent starters from considering Colorado long-term. Since DePodesta left baseball 10 years ago, Rockies pitchers have a 5.17 ERA, nearly half a run higher than the next-worst team.

Exactly how DePodesta will try to implement change is unclear, particularly because he has no baseball track record since fastball velocities took off and spin rates became king: He is being tasked with, among other things, modernizing the pitching infrastructure of the most pitching-challenged franchise in baseball after being out of the sport during the years when its approach to pitching changed most.

“Certainly, the size of the operation is much bigger than it once was. The specialty of the roles are much different. But that being said, I keep looking and thinking, ‘What are the similarities?’” DePodesta said. “And I still think it’s about building a great culture. I still think it’s about building real consistency from the major league team all the way down through the Dominican team and amateur operations, etcetera. Now, how you go about that is a little different just because of the sheer volume of people and even some of the niche roles people have, but I think the main task is the same.”

The contours of DePodesta’s vision for a winning Rockies machine are not yet clear, let alone the specifics. He still needs to hire a general manager and build out what was a limited front office. He also still needs to hire a manager, which takes time. He talked about tapping into the experience that exists in the Rockies’ baseball operations department, which suggests he is not planning the kind of large-scale purge like new Washington Nationals president of baseball operations Paul Toboni orchestrated when he took over an organization that had also developed a backward reputation. Perhaps it is because he is just days into what others view as a multiyear rehabilitation project, but DePodesta indicated a surprising level of flexibility in his blueprint.

“I actually brought up [our identity] with our entire organization late last week. It was one of the things I said to them; it was probably the main theme of our call. That’s for us to decide. It’s not for me to decide,” DePodesta said. “I’m really curious for all of us to get together as an organization and decide what it is we want to be and then stick to it and figure out how we’re actually going to implement it.”

After a decade without him around, the rest of baseball is curious to watch him try.

The post A ‘Moneyball’ architect is back in MLB to turn around another franchise

appeared first on Washington Post.