The buzzword “circularity” has gained prominence this year as a note of caution about the companies building out massively expensive infrastructure needed to support mind-bending artificial intelligence applications. Big Tech leaders — including OpenAI, Nvidia, Google, Oracle, Meta and others — are investing billions in each other and other companies, propping up one another’s finances, potentially beyond where logical and prudent spending would otherwise have taken them.

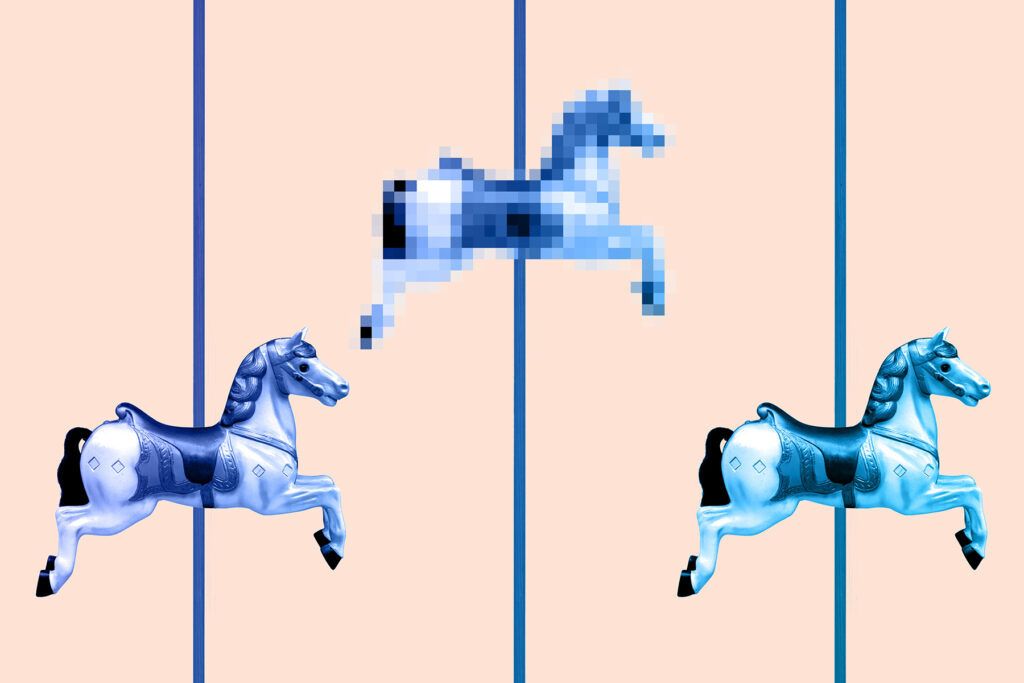

The money flows in a circular fashion — from one company to another and then back again, ultimately, to where it started — not necessarily creating value along the way. The term is meant to warn investors to temper their AI exuberance by explaining one of its chief risks, namely that feverish periods of investment drive booms that lead to busts. If the pumping up isn’t warranted, the puncture is all the more painful.

Wall Street loves its catchphrases, the better to simplify esoteric, tedious or just plain risible concepts. This year’s “TACO” trade, for instance, assured investors that “Trump Always Chickens Out,” making it okay to bet on stocks that otherwise might decline due to ill-advised tariffs. “SPACs,” flimsy investment vehicles for bringing shares of dodgy companies to public markets, is a whole lot more fun to write and say than special purpose acquisition companies.

What’s amusing about “circularity” to market watchers of a certain age is that we’ve seen this movie before — but under a different name. During the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, such deals were referred to as “round-tripping.” One company invested in another, which turned around and used those funds to buy products from the first company. The money made a round trip, puffing up performance without creating profits.

Round-trip, or circular, transactions are not necessarily wrong, though they can be. In some dot-com-era cases, individuals authorized payments and counter-payments intended to bid up the value of two companies, not conduct legitimate business. Executives, notably some who worked for and with the former media giant AOL Time Warner Inc., got into serious legal trouble over this.

Well-traveled money has become the coin of the realm in the AI boom. In September, AI chip king Nvidia announced it would invest $100 billion in OpenAI, the start-up behind the wildly popular ChatGPT. OpenAI promptly unveiled massive investments in SoftBank and Oracle, which are building gargantuan data centers that run on, you guessed it, Nvidia chips. In other words, Nvidia helped to finance the purchase of its own products by investing, directly and indirectly, in its customers — a perfectly legal, if concerning, round trip of capital.

The concern is that demand for AI’s new products might never catch up with the capacity the industry is building. That’s essentially what brought low so many internet companies a generation ago. There was simply too much capital chasing too few good start-ups — and not enough customers to keep them all afloat.

What typically happens at this stage of a speculative boom over a justifiably exciting technology is that some investors begin to fret, which is inevitably followed by stay-the-course, this-time-is-different tut-tutting from market professionals whose livelihoods are predicated on the party continuing.

“While some caution is warranted, we think the better question is not whether today’s deals resemble the dot-com era, but whether the underlying fundamentals do,” wrote JP Morgan Chase’s Stephanie Aliaga and Nicholas Cangialosi. .

There are differences from the earlier era, as there always are. Some of the companies involved, notably tech stalwarts like Google and Meta that got their starts during or just after the dot-com debacle, generate so much cash that even overinvestment doesn’t constitute an existential threat for them. In that sense, their fundamentals are indeed solid.

Yet they and others are borrowing so much to build out AI data centers — Morgan Stanley has estimated that $1.2 trillion will be borrowed over the next three years by just a few AI giants — that if the products they support don’t perform as planned, the losses could be so big they would rock the economy.

All this is confusing for investors, professional and armchair alike, because no one knows when the frenzied activity will end. We merely understand that eventually it will. What the AI boom has in common with the dot-com bubble is that it is built on top of a genuinely new and paradigm-changing technology. The internet really did sink entire industries, create new globe-spanning corporations and change society as we understood it — just as its enthusiasts said it would. That didn’t mean that every company survived. Many were also-rans; some simply were too early.

It will be the same with generative AI, whose innovative ability to do things once the sole preserve of humans will touch nearly every aspect of our lives.

What AI won’t change is that investments only work if the financial returns justify them. It also can’t dampen the animal spirits of investors who think this time is different. They’ll have to learn the old-fashioned way.

The post ‘Circularity’ is a flashing warning for the AI boom appeared first on Washington Post.