This personal reflection is part of a series called Turning Points, in which writers explore what critical moments from this year might mean for the year ahead. You can read more by visiting the Turning Points series page.

The following is an artist’s interpretation of the year — how it was or how it might be, through the lens of art.

Truth is essential, especially now. I believe we are facing a time of anti-intellectualism, persecution and lack of reason.

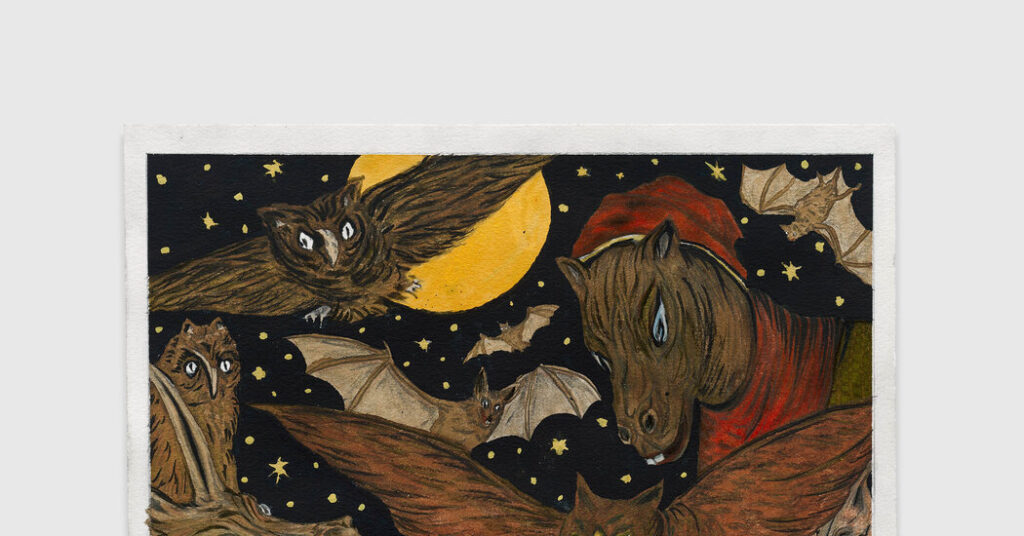

To explore these themes, I created a drawing called “The Sleep of Truth.” I was inspired by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s famous etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” It comes from a series of 80 etchings published in 1799 called “Los Caprichos” or “The Caprices.” I have often returned to works from this series, as they’ve offered endless inspiration and reflection at different points in my life — particularly over the past year.

When Goya produced “Los Caprichos,” there was considerable political turmoil in Spain and throughout Europe. The French Revolution, a period of tremendous social change, was underway, and the Spanish monarchy was persecuting intellectuals, including Goya’s friends. In response, Goya became critical of the aristocracy, violence, religious order and fanaticism. These sentiments are apparent in his work. The late 18th century was also a time of widespread superstition in Spain, and Goya recoiled against these beliefs. Instead, he championed imagination, reason and individualism. There is little doubt that we can draw a line from this part of history to the present.

I spend a lot of time researching historical context and mythology before creating artwork. In “The Sleep of Truth,” which plays with symbolism and the concepts of good versus bad and fantasy versus reality, a host of mythical and monstrous-looking animals are watching a sleeping woman in the foreground of the image. The woman wrote the Spanish word “verdad,” which in English means “truth,” before she fell asleep.

I feel a strong connection to Goya because I’m also drawn to animal mythology. My monstrous-looking animals include bats, owls and a donkey.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always illustrated bats because they are maligned creatures. Bats are often seen as something to be feared and linked with darkness, yet they are an essential part of our ecosystem. Because bats help control the mosquito population, it’s important that we find a way to coexist with them. Every time I draw a bat, I think about this paradox, and at this point, I have a fondness for them.

Owls are another mostly nocturnal creature with a dichotomous origin story that I’ve chosen to feature in “The Sleep of Truth.” In certain cultures, owls are associated with death and bad omens, and as a result, people are often afraid of them. When I hear an owl at night, I am simultaneously a little bit thrilled and a little bit scared that one is going to swoop down and snatch up my dog. Yet, they also represent wisdom and spirituality, and some believe that when you see one, it means you need to pay attention.

Finally, on the left side of the work, I decided to include a donkey because the animal symbolizes stupidity and stubbornness. I think this animal makes a fitting allegory for the tumultuous political times in which we find ourselves.

History is repeating itself as it always does. Some of us are living a nightmare, while others are living in gilded castles. But who are the monsters of today?

Marcel Dzama is a Canadian contemporary artist based in New York. In 2025, his solo exhibition, “Empress of Night,” was on view at the David Zwirner gallery in Los Angeles.

The post A Not-So-Sweet Slumber appeared first on New York Times.