BERLIN — When NATO allies committed to meeting President Donald Trump’s demand that they spend 5 percent of their gross domestic products annually on defense, Trump hailed it as a “monumental win for the United States” that would reduce the burden on U.S. taxpayers of defending Europe.

But there’s been no bigger financial winner from the pledge than the German defense contractor Rheinmetall. Once seen as a declining Cold War relic, the company has emerged as an armsmaking behemoth and a central force in Europe’s remilitarization.

Rheinmetall’s share price has nearly tripled since Trump issued his demand as president-elect last December. Now Europe’s most valuable arms manufacturer, its market value has soared to more than $91 billion from $4.1 billion before the Russian invasion of Ukraine — eclipsing German household names such as Adidas, Bayer, Lufthansa and Volkswagen.

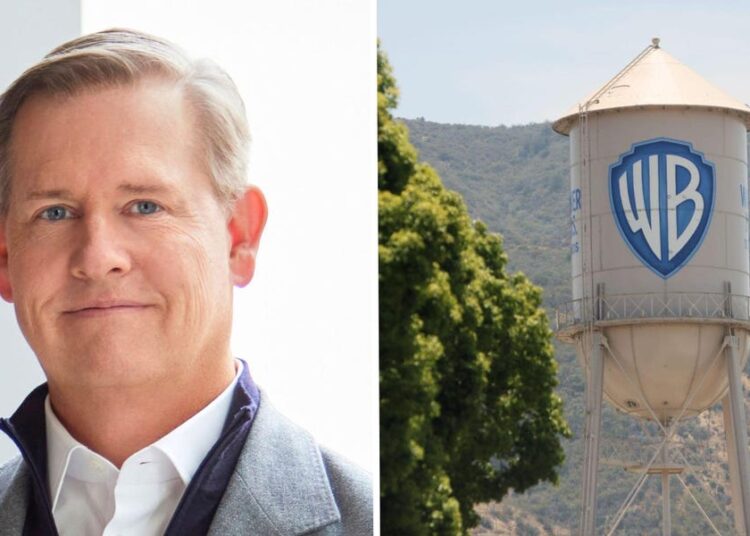

That has made Rheinmetall CEO Armin Papperger the face of Europe’s rearmament. Papperger, 62, with his signature shock of white hair, regularly graces the German evening news and magazine feature stories. He travels with a security detail as large as that of Chancellor Friedrich Merz, following a suspected Russian assassination plot. And he has the ears of prime ministers and presidents, including Volodymyr Zelensky, whom he visited in Ukraine.

“We are becoming a global defense champion,” Papperger said last month, announcing the firm’s latest booming financial report.

Papperger aspires for Rheinmetall’s sales volume to soon match or exceed those of top American defense companies such as Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman — the firms that many expected to profit most from Europe’s huge new defense spending, assuming that the European industry wasn’t up to the task.

But 80 years after the end of World War II, Germany’s arms factories are again running at full tilt. Companies like Diehl, Heckler & Koch and KNDS also crank out firearms and tanks, but no rival — in Germany or across the continent — comes close to matching the growth of Rheinmetall.

For some, it’s a betrayal of the postwar order; for others, the price of sovereignty in an age of renewed aggression.

Faced with the growing Russian threat and concerns that the United States may no longer serve as the continent’s ultimate protector, European leaders have accelerated efforts to build independent defense capacity. It’s no easy feat. Key projects — from a proposed drone shield on Europe’s eastern flank to a next-generation fighter jet led by France, Germany and Spain — have stalled, even as leaders from Paris to Warsaw insist Europe must develop the ability to defend itself.

For Rheinmetall and its CEO, that anxiety has become highly profitable.

It’s a remarkable transformation from when Papperger took over 12 years ago. At the time, German defense spending hovered just above 1 percent of GDP, and public sentiment favored pacifism over preparedness. Founded in 1889 to produce steel and ammunition for the German Empire, the Düsseldorf-based company seemed destined for decline.

Papperger was an unlikely baron of industry. Born in Mainburg, north of Munich, he studied mechanical engineering at the University of Duisburg before beginning his career at Rheinmetall in 1990 as a quality-control engineer. In 2013, he was head of the company’s business units overseeing vehicle systems, weapons and ammunition when he was appointed chief executive.

At the time, Rheinmetall was adrift, with a share price under $50. Its current price is nearly $2,000.

“Before the war in Ukraine, I would have said Rheinmetall was one of those German arms companies becoming increasingly less important and likely to be displaced internationally,” said Ulrich Kühn, head of arms control research at the Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy, a Hamburg-based policy organization.

Then came Feb. 24, 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced Germany — and much of Europe — to confront a world many believed consigned to history. Then-chancellor Olaf Scholz declared a Zeitenwende, or “historic turning point,” pledging over $100 billion to rebuild the military. Since then, Germany has relaxed its debt limits to allow for up to $1 trillion of spending on defense and related infrastructure over the next decade.

Few companies were ready for Germany’s Zeitenwende. Rheinmetall was.

Within months of the Russian invasion, Rheinmetall was producing artillery shells, tank guns and armored vehicles such as the Leopard 2 and Lynx, which became staples of Ukraine’s defense. Now the continent’s top producer of tank and artillery ammunition, Rheinmetall is building plants across Europe, from Spain and Hungary to Ukraine and Latvia, as well what’s expected to be Europe’s largest munitions factory in the northern German village of Unterlüess.

Revenue, around $11.6 billion last year, is projected to increase by 25 to 30 percent this year. Rheinmetall declined a request to interview Papperger, but on a call last week with foreign correspondents in Germany, he said he anticipates that revenue could hit nearly $140 billion in coming years and that the workforce could grow to more than 40,000 in the next two years.

“It will very likely grow into one of the world’s leading arms companies, if it isn’t already in certain areas,” Kühn said.

If war has been a boon for Rheinmetall, peace could slow its meteoric growth. But even if Russia agrees to a ceasefire in Ukraine, Papperger told journalists last week, he expects business to remain strong because of the deterrence capability NATO now demands.

“If there were no war tomorrow — which everyone wishes, and which I truly also wish — then what we are currently sending to Ukraine and producing for Ukraine would instead go into NATO member stockpiles and also into Ukraine because Ukraine is empty,” he said. “They will still need equipment in case there is another attack.”

The German government will be one of the company’s biggest customers. As all efforts shift to arms, Rheinmetall has put its struggling civilian automotive components unit up for sale.

“Papperger seized the opportunity,” said Ben Schreer, executive director of the Europe office at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “He said, ‘Look, we can really position ourselves as a major provider of artillery production, armored vehicles, but can also gradually branch out in other important areas, into autonomous systems, missiles and rockets, satellites.’”

The company’s surge comes as NATO leaders push for faster production and innovation. At the NATO-Industry Forum in Bucharest last month, Secretary General Mark Rutte said spending commitments must translate into real procurement: “Jets, tanks, ships, drones, ammunition, cyber and space capabilities.”

Rheinmetall has answered the call, recently introducing its Panther battle tank, which features AI-assisted targeting and modular armor, and beginning production of fuselage components to be supplied to Northrop Grumman for the F-35 fighter jet.

Rheinmetall’s order backlog has swelled to nearly $75 billion and is expected to top $93 billion by year’s end. The company attributes the increase to major new contracts and “high military demand.”

The backlog highlights the risks of Germany’s — and Europe’s — extreme dependence on Rheinmetall, particularly if it can’t deliver all these orders on time, said Christian Mölling, director of European Defense in a New Age, a Germany-based think tank.

At the same time, the urgency of the security situation leaves little choice. German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has set a goal of being “kriegstüchtig,” or “war-ready,” by 2029 — the year some experts say Russia could be in a position to attack a NATO member state.

“Neither the government nor the industry has a second shot,” Mölling said.

To some, Papperger is a business-minded patriot answering a historic call; to others, a profiteer. Last year, he received a $3.9 million pay package, according to company documents. But he also held 160,000 shares in the company, the German magazine Der Spiegel reported, worth more than $324 million.

His image — like his company’s — straddles an uneasy line between security and militarism in a nation long defined by postwar restraint.

Jonah Fischer of the activist group Rheinmetall entwaffnen (Disarm Rheinmetall) said Papperger “must be held personally accountable — not just because he is a profiteer, but because he represents this entire policy.”

The group has been organizing protests against Rheinmetall and the German arms industry since 2018, including a march in August through Papperger’s neighborhood in Büderich, north of Düsseldorf.

Papperger insists Rheinmetall’s mission is defensive. Yet he has acknowledged that Europe’s appetite for arms marks an uncomfortable cultural shift. To soften Rheinmetall’s image, Papperger has invested in community projects and sports sponsorships, including a major deal with Borussia Dortmund, a top soccer club. Critics call it moral window dressing.

Rheinmetall’s meteoric ascent has also made Papperger a target. NATO confirmed reports this year of a Russian military intelligence plot to assassinate him, part of a broader campaign against European arms executives aiding Ukraine. Earlier, arsonists set fire to the garden house at his home in northern Germany; a left-wing group claimed responsibility, accusing him of “profiting from war.”

For Moscow, Papperger is the embodiment of Europe’s resolve to rearm. Russian President Vladimir Putin has reportedly denounced him by name in meetings with top commanders.

As defense giants like Rheinmetall rise, the European Union is struggling to coordinate its military efforts. French lawmakers have voiced concern about Berlin’s defense industry strategy, with one warning that it increases “the competitive logic even more, at the expense of the cooperative logic.”

France once aimed to lead Europe’s defense consolidation — a vision backed by President Emmanuel Macron — but financial reality has put Germany in the driver’s seat. “At the end of the day, the question is, who has the money?” Mölling said, pointing to Germany’s rapid spending growth. “It’s as simple as that.”

Led by Rheinmetall, Germany dominates the production of heavy land equipment now most in demand. France remains a leader in air defense, though tensions have increased amid the possible dissolution of the joint fighter jet program and Germany’s launch of a “sky shield” initiative without Paris.

On the call with international journalists, Papperger rejected the idea that Europe had grown too dependent on Rheinmetall. “There is competition, and we are positioning ourselves within that competition,” he said, adding, “We stand for the free market economy, we stand for competition — and of course, we stand for cooperation with our French friends.”

Addressing defense industry executives last month, NATO’s Rutte urged unity. “There are great business opportunities for all of you,” Rutte added, “and real benefits for us all.”

Ellen Francis in Brussels contributed to this report.

The post German armsmaker wins big from Trump’s NATO spending demands appeared first on Washington Post.