It might seem improbable today, given the Trump administration’s penchant for brazenly bullying federal employees, but half a century ago my father-in-law, a federal employee, resisted an order from the Nixon White House — and was ultimately rewarded for it by his superiors.

Dr. Barney Malloy, my wife’s father, was a staff psychiatrist at the Central Intelligence Agency from 1958 to 1989. After he died in August at 96, my wife and I found documents in his files that detailed his conduct during a devious episode of presidential overreach. His personal integrity was notable, but even more important, as a political lesson for today, was that his superiors at the C.I.A., despite their shortcomings, were not entirely beholden to a corrupt president.

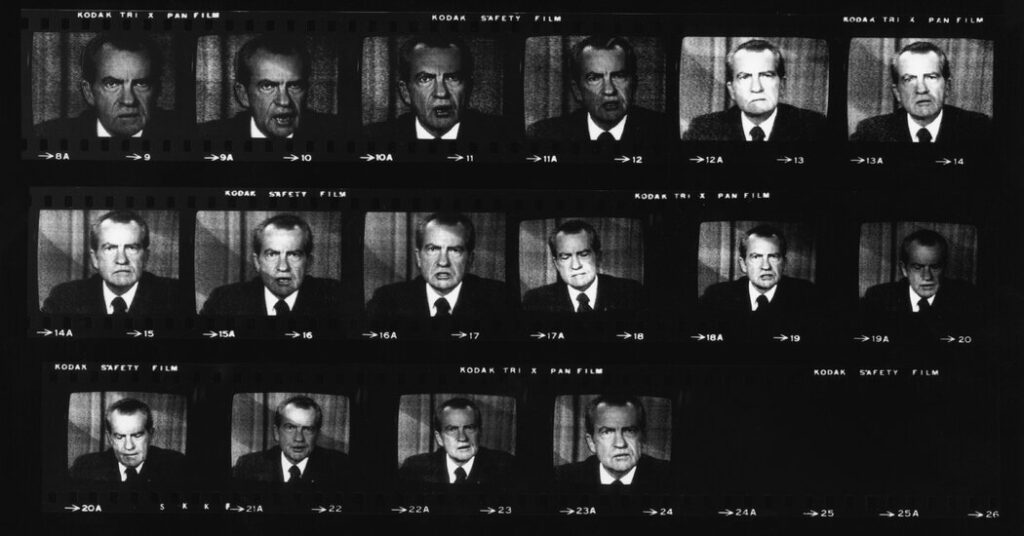

The story began in the summer of 1971, when Richard Nixon, through subordinates, ordered the C.I.A. to create a psychiatric profile, not of a foreign leader, but of an American citizen: Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg was a military analyst and a former Defense Department employee who had infuriated Nixon by leaking the classified documents known as the Pentagon Papers. The documents showed that the executive branch had lied to Congress and the public about the extent of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Nixon sought to neutralize these revelations — and to exact revenge — by maligning Ellsberg and his mental health.

By that time, Barney was the chief of the C.I.A.’s psychiatric division. When presented with the White House’s request for an agency profile of an American citizen, he expressed concern that it might be improper. But his supervisor assured him that Richard Helms, the director of the C.I.A., had approved it. So Barney and a colleague wrote up a psychiatric study based on a review of newspaper and magazine articles about Ellsberg as well as a few interview reports from F.B.I. informants. The study concluded that Ellsberg was a brilliant man and an altruist who had been acting out of “what he deemed a higher order of patriotism.”

The White House was not pleased with this assessment. Three days after submitting the study, Barney was summoned to a meeting with Howard Hunt, a member of a White House special investigations group known as the Plumbers that would later plan and carry out the Watergate break-in. Hunt expressed his hope that Barney would write up a juicier psychiatric study exposing “Oedipal conflicts or castration fears” or other embarrassing details that could be used to “defame or manipulate” Ellsberg, according to an affidavit that Barney submitted two years later to the Senate Watergate committee.

Hunt also pressured Barney to keep their discussion confidential. But Barney explained that he was duty-bound to consult with his superiors. After Barney alerted the C.I.A. leadership to Hunt’s request, Helms and the agency’s deputy director, Gen. Robert Cushman Jr., agreed to grant the request, honoring an informal arrangement that Cushman had made with the White House aide John Ehrlichman for the C.I.A. to help Hunt.

Barney seems to have done his best to slow-walk the second psychiatric report on Ellsberg. After several months of White House pressure, he finally handed it over. But instead of giving the administration what it wanted, he doubled down on the earlier findings, describing Ellsberg as a man of “dazzling intelligence” and suggesting that his main reason for leaking the Pentagon Papers was his conviction that the executive branch “should not alone have so much unshared power as to plunge the country into war and the misery and death that it brings.”

It is not clear how the White House reacted to this report. What we do know is that Hunt was already taking matters into his own hands: He organized a team of burglars to break into the office of a psychoanalyst in Beverly Hills, Calif., whom Ellsberg had seen. The C.I.A. helped by providing Hunt with a special high-speed camera hidden inside a tobacco pouch and by processing the film after the break-in.

Later, the C.I.A. admitted — halfheartedly — that it had lost its way during this time. In Barney’s files, my wife and I found the transcript of a speech by the C.I.A. director William Colby at an agency awards ceremony in 1974, in which Colby acknowledged that he and his predecessors “made a couple of little mistakes, a couple of short steps in the wrong direction.”

At that ceremony, Colby also awarded Barney the agency’s Intelligence Medal of Merit. He praised Barney for having “demonstrated exceptional perception and courage under very awkward circumstances to bring to the attention of the top echelon of the agency his reservations about support to an operation which proved to be beyond the jurisdiction of the agency.”

I wonder how different things might be for Barney today. Although he worked for an agency that was undoubtedly flawed, his superiors were willing to tolerate principled pushback. He was allowed to be honest. Unlike James Comey, Alexander Vindman, Sally Yates, Christopher Krebs and other vocal government critics of President Trump, he wasn’t fired, hounded or investigated. Instead, he was able to continue serving his county as best he could.

Dan Sturman is a documentary filmmaker whose films include “Nanking” and “Twin Towers.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post The Crucial Lesson of a Forgotten Nixon-Era Episode appeared first on New York Times.