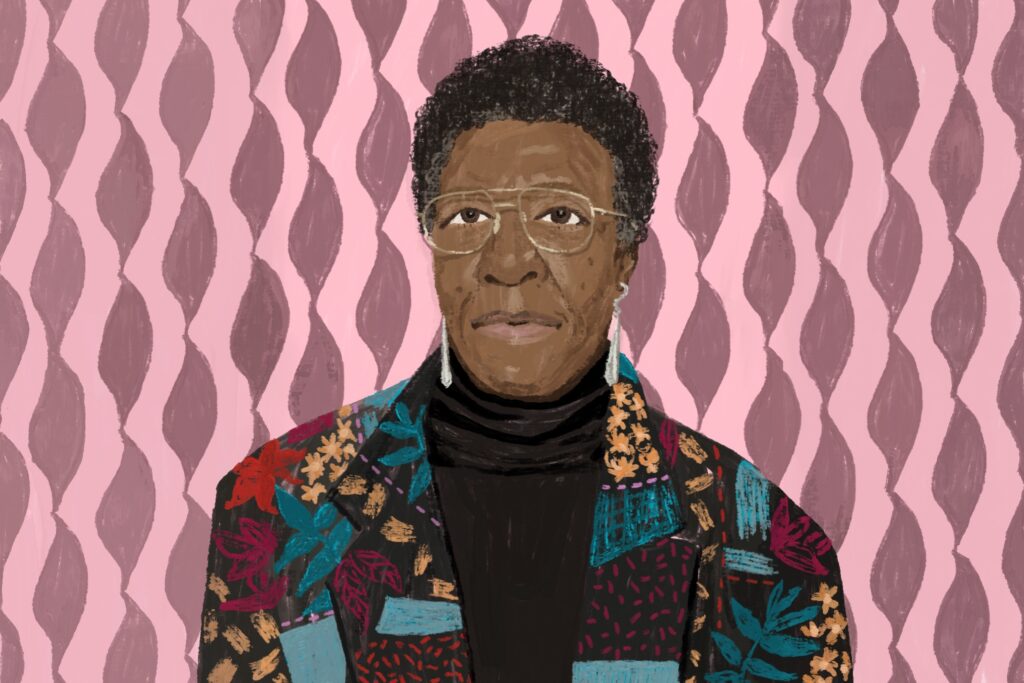

“I am too alone, too slow, too lazy, too undisciplined, too little in my big body. I talk too much — and too little — saying too often the wrong thing.” Octavia Butler wrote these words in her personal journal on Nov. 23, 1983. By that point in her career she’d published five novels, but that output hadn’t resolved her inner doubts. When writers, artists of any kind, attain a certain level of prominence, it can be easy to imagine that they were destined for their acclaim, that their greatness was inevitable. But that doesn’t serve them, or us. Instead, the portrait of Butler not simply as a genius, but as a human being riddled with insecurities and despair, is what makes “Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler”by Susana M. Morris such a moving and welcome biography.

The first science fiction writer, of any gender or race, to win a MacArthur “genius grant,” Butler was born in Pasadena, California, in 1947, the daughter of a domestic worker and a shoeshine man. Her mother was also Octavia, so in childhood Butler went by her middle name, Estelle, with most of those who knew her. Before Estelle came along, her parents lost four infant boys; her father died when she was a young girl. Estelle was then raised by her widowed mother and extended family.

A bookish child, Estelle began reading science fiction magazines, like Amazing Stories and Fantastic, at the age of 14. She read foundational writers in the genre: Robert Heinlein, John Brunner, Theodore Sturgeon and Frank Herbert. Marion Zimmer Bradley, Ursula K. Le Guin and Zenna Henderson were writers who particularly excited her. She was doing what any good writer should, learning what’s been done before, at its best, to help her figure out what she might attempt herself.

But her family treated her ambitions with skepticism. “Although Estelle’s family encouraged her voracious reading, they generally viewed her writing with bemused skepticism,” Morris writes. “‘Negroes can’t be writers,’ her aunt had told her.” Morris is quick to state that Butler’s aunt wasn’t being malicious so much as realistic. “It was a gentle but firm admonition to get her niece’s head out of the clouds, to save her from further disappointment and inevitable embarrassment.” It was also an honest assessment of the possibility for a child like Estelle to become a writer at all. There had never been such a thing, as far as her aunt knew, so how could it be done?

Her work, Morris writes, “imagines counterpasts and counterfutures for Black people while telling the story of the rise and fall of the American project, charting the expansion of global imperialism, and forewarning the end of humanity as we know it because of climate change.” The dystopian overtones of the past decade have helped that work find renewed relevance and a sizable audience of new readers.

In perhaps her most famous novel, “Kindred” (1979), a 26-year-old Black woman named Dana time-travels between her present day, in 1976 California, and a Maryland plantation in the antebellum South. Her complicated and emotionally painful mission involves saving the life of a White boy, part of a family of enslavers. Morris describes it as the novel that “most directly articulates the issues that animate [Butler’s] writing. It is a novel about hierarchy and ethics, about nature versus nurture, and about how futile it is to try to escape one’s personal and collective past.” Butler often spoke of writing the book in response to criticism by some Black people in the 1960s that their ancestors hadn’t done enough to fight slavery. “I am the daughter of a maid and a bootblack, the descendant of slaves,” Butler wrote in her journal the year before “Kindred” was published. “I climb upon the bones of those who survived hell.” Morris writes: “She thought that if people were more educated about slavery, they could be more empathetic not only to history, but regarding their own experiences.”

“Parable of the Sower,” first published to acclaim in 1993, is told as the journal of Lauren Olamina, a Black teenager living in a California ravaged by the effects of climate change and extreme income inequality. Since Lauren’s first diary entry is dated 2024, readers in recent years have heralded the book as especially predictive. “Octavia’s work was prescient then and seems downright prophetic today,” Morris writes. “But she wasn’t a prophet, not in the usual sense of the word, but an ardent surveyor of history and a deeply thoughtful intellectual who believed that her writing could positively change the course of history. This conviction — that imagination coupled with careful observation and steadfast action and collaboration could help shape our collective future — lies at the heart of why her work matters so profoundly.”

But no assessment of Butler is complete without the emotional effect she has on many of us. Admiration and respect are part of our feeling, of course, but there’s more. Morris sums it up well in her introduction: “Octavia E. Butler came into my life at the exact moment when I needed her. It was the summer of 1996. I was fifteen — shy, awkward, and nerdy — and trying to figure out who I was. I knew I was the daughter of a single mother, a Jamaican immigrant. I knew I was smart. … But I felt the weight of all that I was not. I wasn’t middle class, or popular, or pretty. I was an accidental loner who spent her Saturdays taking two or three buses to find a well-stocked library.”

Morris goes on to discuss being in the science fiction section of the library and seeing the picture of a Black woman on the cover of a book. “I was immediately enthralled and grabbed the book. It was called ‘Parable of the Sower’ by an author I’d never heard of — Octavia E. Butler.”

Great writers, like Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison, inspire esteem and even awe, but few, in my experience, are also able to provoke intimate identification, to seem like a person of great accomplishment who is also, somehow, deeply relatable in a personal way. Butler strikes me as such a writer, and “Positive Obsession” only served to deepen my affection. The book is a very fine examination of her books, how she wrote them, what inspired her, and the highs and lows of her career. But Morris’s most ingenious choice is to focus on the most personal elements of Butler’s life as well, evidenced by the journal entries quoted throughout.

Morris writes, “Octavia was only fifty-eight years old when she died suddenly. On February 24, 2006, she fell and hit her head on the cobblestone path outside her home in Seattle, after what was seemingly a stroke.” Morris remembers being in grad school and stopping by her English department, being told the news, a collective shock coursing through the people there in the mail room. Obituaries ran in The Washington Post and the New York Times, on NPR and in many other outlets. The New York Public Library hosted a tribute to her life. Butler’s editor, Dan Simon, eulogized her this way: “Does it ever seem to you that there are people among us who hold up the sky and make the rivers flow? People who are just like other people, just like the rest of us, only different?” All this for a bookish, shy kid from Pasadena.

In her journal, Butler wrote: “I have no children. I shall never have any. American Black children will be mine. My fortune will be spent motivating and educating them while I live and after my death.” Morris’s biography serves as proof that this goal was met. As does my career, and the careers of so many other Black writers I know who have, to varying degrees and across several genres, believed we could be writers because Octavia Butler proved it so.

Victor LaValle is the author, most recently, of the novel “Lone Women.”

Positive Obsession

The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler

By Susana M. Morris

Amistad. 247 pp. $29.99

The post ‘Positive Obsession’ shows Octavia Butler as a very human icon appeared first on Washington Post.