Consumer Prices Rose 2.8 Percent Through November, a Sign of Sticky Inflation

Consumer prices increased moderately in October and November, according to the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation gauge. Data released on Thursday...

Are You Watching Porn the Wrong Way?

Every so often, people panic about porn addiction, probably unnecessarily. They think that watching more porn causes some kind of...

Trump Unveils World’s Tackiest Logo for His $1B Grift

The logo of President Trump’s controversial new peacekeeping grift has been exposed as a cheap knock-off of the United Nations...

Coyote Spotted Swimming to Alcatraz Island for the First Time

You know Alcatraz Island? The notorious prison from which three men made a daring escape back in 1962, never to...

Bojangles wants New Yorkers to ditch their bagels for biscuits. It could reignite the breakfast wars.

The Southern chicken chain is going after the city's bagel-lovers with its menu of biscuit breakfast sandwiches. Erin McDowell/Business InsiderBojangles...

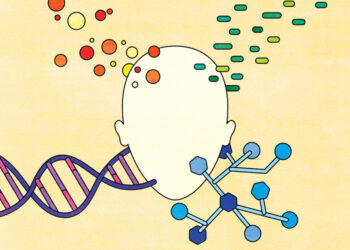

7 surprisingly hopeful things we’ve learned about dementia

If you are like a lot of people, you might be anxious about the risk of getting dementia as you...

The biggest surprises and snubs of the 2026 Oscar nominations

Oscar nominations landed Thursday morning and you’d really have to be a curmudgeon to complain, what with the year’s two...

Trump Returns to a Familiar Role: Sowing Trade Chaos

For four days, President Trump had once again dangled the prospect of a trans-Atlantic trade war as he threatened to...

Protester Who Interrupted Service at Minnesota Church Is Arrested, Officials Say

The Justice Department said on Thursday that it had arrested one of the demonstrators who interrupted a church service in...

The world’s oldest cave painting was just discovered — and it could rewrite origins of human history

It was a Cro Magnon opus. Europe might not be the birthplace of human symbolic culture as previously thought. International...