Hamilton O. Smith, who transformed molecular biology with his discovery of enzymes capable of precisely cutting DNA, a finding that ushered in the first genetically engineered medications and brought him the Nobel Prize, died on Oct. 25 in Ellicott City, Md. He was 94.

His death, which was not widely reported at the time, was confirmed on Friday by his son Derek. Dr. Smith died in Derek Smith’s home, where he had been living for the last few years. He had spent much of his career on the faculty of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Dr. Smith’s breakthrough finding led to one of the most ubiquitous tools in biotechnology. The discovery — the first in a class of gene-cutting enzymes that became known as restriction enzymes — elevated the field of molecular biology to new heights and ultimately aided disciplines as disparate as cloning, crime lab forensics and genomics. His work essentially handed scientists the power to isolate, analyze and manually move discrete sequences of DNA.

The discovery of restriction enzymes “definitely belongs there with other major milestones in molecular biology,” including the discoveries of DNA’s double helix and CRISPR gene-editing technology, said Dr. Robert Margolskee, emeritus director of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. He had studied medical microbiology under Dr. Smith in the 1980s.

In 1968, just a year into a faculty position at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Smith identified a type of protein, an enzyme, in the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae, that had a unique capacity to cut DNA. Working with a graduate student, Kent Wilcox, Dr. Smith noticed that the enzyme appeared to be a defense mechanism used by bacteria. Additional experiments with a postdoctoral fellow, Thomas J. Kelly, revealed that the enzyme not only cut DNA, but also did so strategically, by recognizing certain sequences of genetic coding.

“This was one of the most important discoveries in molecular biology,” said his longtime friend and collaborator Dr. J. Craig Venter. “Restriction enzymes are the molecular scissors that cut the genetic code at specific points, and that’s why they’re such important tools. They are what bacteria use to destroy foreign DNA that enters their cells.”

Those foreign genes are from bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria. When phages invade, they insert their genes into bacteria to replicate and create more phages. Bacteria fight back, releasing enzymes to slice phage genes into harmless pieces, restricting their replication.

The enzyme Dr. Smith isolated was named HINDII, the first Class II restriction enzyme ever identified and a member of a group that has since grown to more than 3,500. They are laboratory workhorses, capable of cutting DNA’s spiraling double helix at multiple target sites.

In 1969, Dr. Daniel Nathans, a Johns Hopkins colleague of Dr. Smith’s, used the newly isolated HINDII to analyze genes from the simian virus, SV40, which can cause tumors in some nonhuman primates. When Dr. Nathans exposed SV40’s genes to HINDII, he was able to determine where viral genes began and ended. He also identified a gene in SV40 that coded for a tumor-making protein. At that time, no one had studied a viral gene in such detail.

The medical benefits of HINDII emerged soon after Dr. Smith’s discovery. To treat diabetes, doctors had long relied on either purified bovine or porcine insulin, both imperfect solutions. HINDII helped lead to the creation, in 1978, of insulin based on the human genetic code, a better alternative.

Synthetic human insulin was first produced in E. coli, whose DNA was cut open using restriction enzymes, then spliced with a cloned gene carrying human insulin’s genetic code. This created a recombinant DNA molecule, or DNA combined from two sources. The recombinant molecules fooled E. coli into making the human hormone and, as the bacteria multiplied, so, too, did the insulin.

“With the help of restriction, practically any gene could be forced to produce protein, first in E. coli, then in other cell types,” said Gábor Balázsi, the Henry Laufer professor of biomedical engineering at Stony Brook University on Long Island.

Dr. Smith shared the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Dr. Nathans, who died in 1999, and the Swiss microbiologist Werner Arber, who discovered a Class I restriction enzyme. The Nobel Committee referred to restriction enzymes as “chemical knives.”

Dr. Venter, himself a pioneering biotechnologist who founded several independent research institutions, including the Institute for Genomic Research, where he and Dr. Smith collaborated beginning in 1995, said of Dr. Smith, “Most Nobel laureates go into quasi-retirement after they win the prize, but he made even more important contributions.” He called him a “gentle giant,” alluding to Dr. Smith’s height, about 6 feet 5.

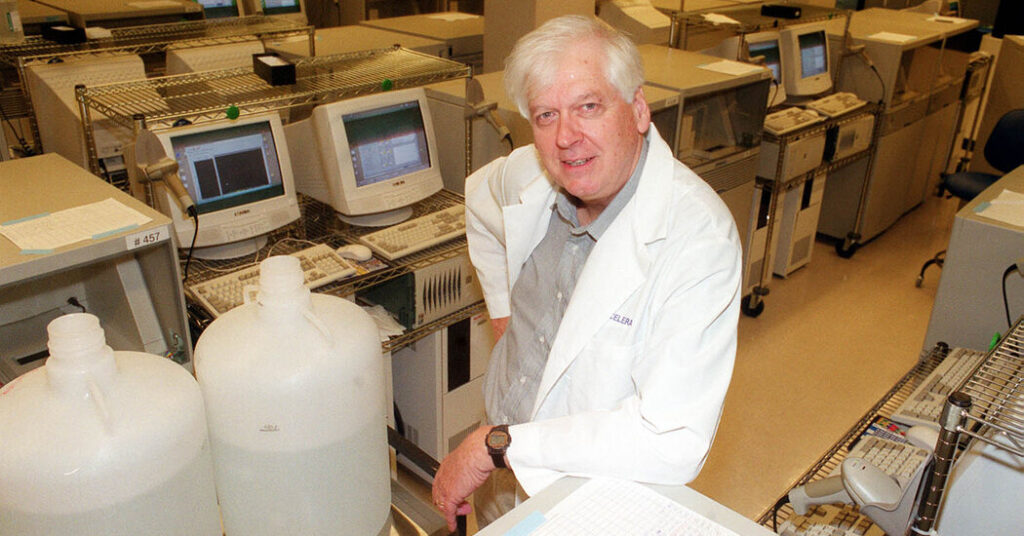

After more than 30 years at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Smith retired in 1998 to join Celera Genomics in Rockville, Md., where Dr. Venter was president, becoming part of a team that raced to sequence the human genome. The effort was separate from the government-backed Human Genome Project. Dr. Smith was senior director of DNA resources at Celera.

He moved to San Diego in the early 2000s to lead research efforts at the J. Craig Venter Institute (it also has research facilities in Rockville). At nearly 79, he and a team of researchers there made history when they announced the creation of an artificial bacterial cell, which was engineered in a laboratory.

Hamilton Othanel Smith was born on Aug. 23, 1931, in Manhattan to Bunnie Othanel Smith and Tommie (Harkey) Smith. His brother, Norman, was born a year earlier in Gainesville, Fla., where Bunnie, who went by B, had been a professor of education. The family had moved to New York so that the father could begin his doctoral work at Columbia University.

In 1937, the family moved to the Midwest, where Bunnie had accepted a faculty position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In his Nobel biography, Dr. Smith recalled that his father was “perpetually working and writing.”

During their teens, the Smith brothers used the money they earned from delivering newspapers to transform the family’s basement into a subterranean world of science. “My brother and I spent many hours in our basement laboratory stocked with supplies purchased from our paper route earnings,” Dr. Smith wrote.

He graduated in 1948 from the University Laboratory High School in Urbana, where he excelled in math and science and was one of three students who graduated from the school between 1935 and 1948 and who later won a Nobel.

He graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1952 with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and received a medical degree from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in 1956. That summer, he started an internship at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, where he met Elizabeth Bolton, a nursing student who would become his wife.

Mrs. Smith died in 2020, and their son Barrett died in 2018. In addition to their son Derek, he is survived by three other children, Joel, Bryan and Kirsten; 12 grandchildren; and 15 great-grandchildren.

At his death, Dr. Smith held the position of distinguished professor emeritus at the J. Craig Venter Institute. Ham, as he was known to friends and colleagues, continued to contribute research past the age of 90.

“He was a scientist from Day 1,” Dr. Venter said. “The Venter Institute wouldn’t be what it is today without Ham Smith.”

Ash Wu contributed reporting.

The post Hamilton Smith, Who Made a Biotech Breakthrough, Is Dead at 94 appeared first on New York Times.