Venezuela sits on more oil than Saudi Arabia, Russia, the United States and every other country. Yet, it produces and sells only about 1 percent of the crude the world is using.

President Trump’s recent threats against the Venezuelan government and his administration’s strikes on boats in the Caribbean Sea have cast fresh attention on the country’s energy wealth, which has tantalized generations of oilmen.

It is hard to know what role oil may end up playing in the tussle between the Trump administration and the government of President Nicolás Maduro. But oil has long been central to U.S.-Venezuela relations.

How much oil does Venezuela have?

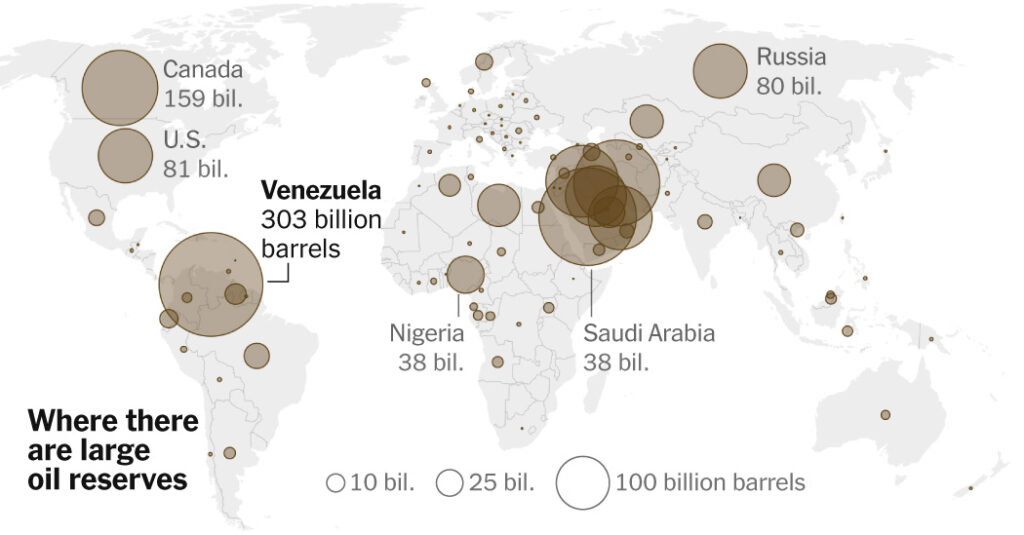

Venezuela has roughly 17 percent of the world’s known oil reserves, or more than 300 billion barrels, according to the Oil & Gas Journal, an industry publication. In other words, that’s how much oil experts believe could be extracted from the country’s territory.

To put that in context, the United States, the world’s top oil producer, has an estimated 81 billion barrels of proven reserves.

Venezuela pumped almost 5 percent of the world’s oil in 1997, but years of mismanagement, underinvestment and U.S. sanctions have squeezed output. The difficulty of extracting the country’s tar-like oil has also complicated matters.

The United States used to buy most of Venezuela’s oil, but that trade stopped in 2019 after the first Trump administration imposed sanctions on the country’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela. Shipments to the United States resumed in 2023, but volumes have remained low. Most of Venezuela’s crude now flows to China.

Which oil companies do business in the country?

Venezuela has seesawed between welcoming private oil companies and asserting state control over the industry.

Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan president who died in 2013, partly nationalized the industry nearly two decades ago, forcing foreign oil companies to accept worse contract terms without compensation. Some of those companies balked. Only a few Western oil and gas producers still operate in the country, including Chevron, the second-largest U.S. oil company, and Italy’s Eni and Spain’s Repsol.

These companies have made a bet that doing business in Venezuela, while difficult and costly, will eventually be worth the effort.

The biggest of the group is Chevron, which has been operating in Venezuela for more than a century and produces around a quarter of the country’s oil. The company’s operations have given Venezuela a financial lifeline and mean that, even today, some of the country’s oil flows to refineries on the Gulf Coast of the United States, where it is made into fuels like gasoline and diesel.

“We play a long game,” Mike Wirth, Chevron’s chief executive, said last month at an event in Washington. The company, he added, “would like to be there as part of rebuilding Venezuela’s economy in time when circumstances change.”

Repsol and Eni produce natural gas offshore that Venezuela uses to generate electricity. At times, the country paid for this gas in oil, which Repsol and Eni had been allowed to export. But this year, the United States blocked such trading, meaning those companies are no longer being paid for the gas they produce.

Repsol and Eni have been in talks with the U.S. government in hopes of resolving their financial predicament, they have said.

Companies that left Venezuela include ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil. Those businesses have spent years trying to get the country to repay them for the assets it seized. They have had little success.

Citgo Petroleum, which is owned by Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, operates three U.S. refineries and has been at the center of a legal battle to force the Venezuelan government to satisfy its debts.

Last month, a federal judge ordered the refiner to be sold to an affiliate of Elliott Investment Management, Amber Energy, for $5.9 billion, a fraction of the more than $20 billion owed to companies tied to that case, court records show. The Venezuelan government, Citgo and others have appealed the decision.

“That kind of on-again, off-again pattern might seem like the sort of thing that dissuades investment,” said Kevin Book, managing director of ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington research firm. “The flip side of that is that Venezuela’s resource is the largest in the world.”

What could happen next?

It’s hard to know.

Something resembling the status quo could continue for a while. If Mr. Trump follows through with strikes or other military action in Venezuela, that could further destabilize the country’s fragile oil industry, at least in the short term. Or a negotiated deal with Mr. Maduro could set the stage for a new era of foreign investment in Venezuela.

Many oil companies would most likely be eager to return to the country, not least to recover what its government took from them.

Venezuela’s resources also remain strategically valuable for the United States. American oil production is widely expected to level off after more than 15 years of rapid growth. Should global demand continue to grow through midcentury, securing new production outside the Middle East and Russia will become more strategically important, said Francisco J. Monaldi, who leads the Latin America energy program at Rice University in Houston.

“The U.S. would love to have an alternative source of supply in those scenarios,” Dr. Monaldi said.

Venezuelan oil is especially attractive to U.S. refiners because it is heavier than what is available domestically. And it takes relatively little time to ship the oil to the Gulf Coast, where facilities are configured to process a mixture of cheaper, heavier oil and more expensive light oil.

The value of Venezuela’s oil is not lost on Mr. Maduro, who recently accused the United States of trying to “seize Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, the largest on the planet, through lethal military force against the country’s territory, people and institutions.”

Rebecca F. Elliott covers energy for The Times.

The post Lots of Oil, Little Production: What to Know About Venezuelan Energy appeared first on New York Times.