In Bogotá’s historic downtown, a modest government building sits in the shadow of a gilded statue of Simón Bolívar, the 19th-century liberator who freed much of South America from Spanish rule. Inside, on the fourth floor, a manzana del cuidado, or care block, pulses with a different kind of revolution.

On a bright October morning, a circle of small children sat around a turquoise table, wide-eyed as their teacher read a Halloween story. In another room, a group of mothers and grandmothers bent over glass jars and wicks, learning to turn used containers into candles during a recycling workshop led by an official from the city’s environmental division. In the main hall, a half dozen women in sneakers and leggings followed an instructor’s aerobics routine, laughing as they stretched and lunged.

This space is one of 25 neighborhood hubs that have opened across Colombia’s capital since 2020, all part of an ambitious citywide effort to tackle “time poverty” — the lack of time for anything beyond the crushing, invisible burden of unpaid care work that falls overwhelmingly on women.

In Bogotá, a city of 8 million people, nearly 4 million women do some form of unpaid care work, and about 1.2 million dedicate most of their time to it, meaning 10 hours a day or more. Many commute for hours to reach paid care jobs, only to return home and do more unpaid care.

Key takeaways

- Women in Bogotá provide over 35 billion hours of unpaid care work annually — totaling more than one-fifth of Colombia’s GDP.

- Partly to address this, Bogotá is pioneering “care blocks,” neighborhood hubs where women can access free laundry, legal aid, job training, mental health services, and more while their children or elderly relatives receive care on site. The city has opened 25 care blocks since 2020.

- The model is spreading globally. A US city is expected to join in 2026.

At a care block, a woman can access a variety of services while the person she cares for is looked after by teachers and staff nearby. She can hand off her laundry to an attendant, finish her schooling, meet with a lawyer, consult a psychologist, or learn job skills. The scope of activities is not limited to errands, either: she can also read a novel, catch up with friends, or just get some rest. And the system extends beyond the physical blocks — mobile buses bring comprehensive services to rural areas, and an at-home program targets caregivers who support those with severe disabilities and therefore cannot leave their houses.

Bogotá is trying to do something tricky: elevate both care work and caregivers, while also saying, “You shouldn’t have to be doing this so much — you deserve a full life beyond caring for kids, for aging relatives, for your partner.“

Understanding how Bogotá built its care system — and the challenges it faces — offers a template for other cities. And indeed, what started as a local experiment is now gaining traction internationally. Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, expects to open its first care block by this year’s end. Guadalajara in Mexico approved funding for several “care communities” earlier this summer, and care blocks are already operating in Mexico City and Santiago, Chile. Activists and public health officials in England are trying to adapt the model, and a funder is even seeking to pilot care blocks in an American city in 2026.

The novel idea is putting caregivers — not just care recipients — at the center of policy, says Ai-jen Poo, a leading voice in the US care work movement and president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance. Poo traveled to Bogotá in 2023 to learn more and said the program “blew her mind.” Before the pandemic, she added, most people didn’t identify as caregivers per se — even if they saw themselves as moms, parents, children.

“What could be the next big breakthrough is cities putting the idea of a caregiver and intergenerational care at the center of how you design access to services,” Poo said. “That’s the future.”

Behind Bogotá’s care revolution is a women’s movement with teeth.

In 2010, Colombia became the first country to legally require that its government quantify how much unpaid work was being done and by whom. The initial time-use survey, conducted in 2012, found that caregivers provided more than 35 billion hours of labor each year, amounting to more than one-fifth of the country’s GDP. Women did 80 percent of that work.

The political will to do something about those statistics started to build. One movement bolstering women in the city was the Mothers of False Positives, led by women whose sons had been killed by the military in the mid-2000s; the military then falsely presented these men as guerrilla fighters to inflate its own body counts. The mothers transformed their grief into a public reckoning, marching, testifying, and demanding justice — reframing the work of motherhood itself as a form of political resistance.

Bogotá’s social landscape made space for that kind of organizing. Decades of civil war and displacement had reshaped the city, creating an openness to more fluid household structures. Extended families are common, with grandmothers, aunts, and sisters raising children together, often out of necessity. Single mothers aren’t whispered about as moral failures like they sometimes are in the US.

All these factors paved the way for Claudia López’s 2019 mayoral campaign. Lopez had already built a reputation as an anti-corruption crusader who unapologetically centered gender equity. The then-49-year-old ran as an openly gay woman in a Catholic country, aiming to become both Bogotá’s first female and its first LGBTQ mayor — and won with 35 percent of the vote in a tight four-way race.

“The women’s vote was crucial in setting the stage for this,” Ai-jen Poo recalled. “And they were ready with their economic priorities and gave the mayor a mandate, if not the actual solution.”

Care blocks, the signature policy of López’s administration, are built around the “3 Rs”: recognize, redistribute, and reduce. Recognize that care work is real work that sustains society. Redistribute it — not just between women and men, but to care recipients when able, and to the state, employers, and communities. And reduce the overall burden so individual caregivers aren’t consumed by it.

López launched this District of Care System in 2020 through an executive decree, which gave her the authority to create the programs but also meant any future mayor could undo them just as easily. The initiative was allocated 5.2 trillion pesos (about US $1.3 billion) in the city’s 2020–24 development plan — much of it from reallocating existing service budgets and cost savings from turning single-use public facilities into new multi-purpose hubs. López’s administration later helped pass a law through the city council requiring different agencies to fund and run the care system. Unlike a decree, the law couldn’t be undone by a future mayor alone.

Colombia bars mayors from running for consecutive re-election, so as Lopez’s term neared its end, no one knew whether the next leader would continue her signature policy.

Her successor, Carlos Fernando Galán, couldn’t have been more different. The son of Luis Carlos Galán — a presidential candidate assassinated in 1989 for confronting narco-politics and corruption — the younger Galán billed himself as a centrist technocrat focused on fiscal responsibility and data-driven governance. In 2023, he won on a platform of public safety and restoring trust in government, far from Lopez’s more liberal and feminist message.

Galán could have pushed to end the care blocks. But the system had momentum, having earned international attention from the United Nations, funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies for its at-home assistance component, and praise from leaders around the world. All this made it easy for Galán to ride the goodwill and claim credit for the accolades his city kept earning for running programs in spaces most people would never expect.

For 14 years, El Castillo was one of Bogotá’s most notorious brothels—a place where businessmen, mobsters, and foreign clients paid for access to its VIP floors. Its ties to drug trafficking networks made it the target of a 2017 raid, after which the building sat abandoned for three years.

In 2020, the city converted the facility into the Castillo de las Artes — the Castle of the Arts — a cultural hub and care block.

Lebeb Infante, the care block’s director, was matter-of-fact about Castillo’s history and unapologetic about its current clients. “This neighborhood has the highest concentration of sex workers in the locality,” she said. “Many of them are caregivers — they have children, they’re supporting families. We also have a huge migrant population, people fleeing violence in Venezuela and rural Colombia. So the services here have to work differently.”

Offerings must account not only for gender, but for immigration status, which means helping people navigate bureaucracy when they don’t have papers or IDs and need to get certified for work or enroll in school. This particular block has two laundromats instead of one, plus a free clothing closet. “If someone needs pants to go to a job interview, we give them pants,” Infante explained.

El Castillo is also home to an El Arte de Cuidarte, or Art of Care center — the child care component that exists in every care block across the city.

On the day I visited, children’s voices rang out from behind an arched doorway. Streamers in purple and green — Halloween decorations — hung from the ceiling. Like any preschool classroom, it was bright and chaotic, with walls covered in artwork and educational posters.

The Art of Care programs serve a wider age range than traditional daycare, welcoming children from 11 months to 11 years old. Bogotá already has a robust public daycare system: free centers have existed since 1968, managed by the national child welfare agency and the city’s social integration office. These care block programs have a more specific purpose: free up time for caregivers so they can prioritize services, both for long-term goals and their immediate needs.

Parents don’t just drop off their children and leave to run errands all across the city. Many of the errands can be completed right there on site. One of the key challenges for caregivers dealing with “time poverty” is finding space in their day for anything else — their own health concerns or new credentials that could put them on a more secure financial footing. The Art of Care tries to eliminate some of that friction.

Juliana Martínez Londoño, the deputy secretary of Bogotá’s Women’s Secretariat.

Juliana Martínez Londoño, the deputy secretary of Bogotá’s Women’s Secretariat, emphasized that the Art of Care was not meant to compete with the city’s existing daycare infrastructure.“But the Art of Care is much more flexible,” she said. “It can be mobile, it can adapt to different schedules, it can go where caregivers are.”

An even more ambitious vision for the future of child care comes from Camila Gómez, the director of Bogotá’s citywide care initiative. She imagines 24-hour mobile child care centers for women who work night shifts, like bus drivers or recyclers who sort trash before dawn. The service could be more widely available, coming to a university student on exam day, or an employee whose company would pay for the service and get a tax break in return. “The goal is to not limit the Art of Care to people who are taking services at the care block,” Gómez said. “We want to make it for anybody who needs it.”

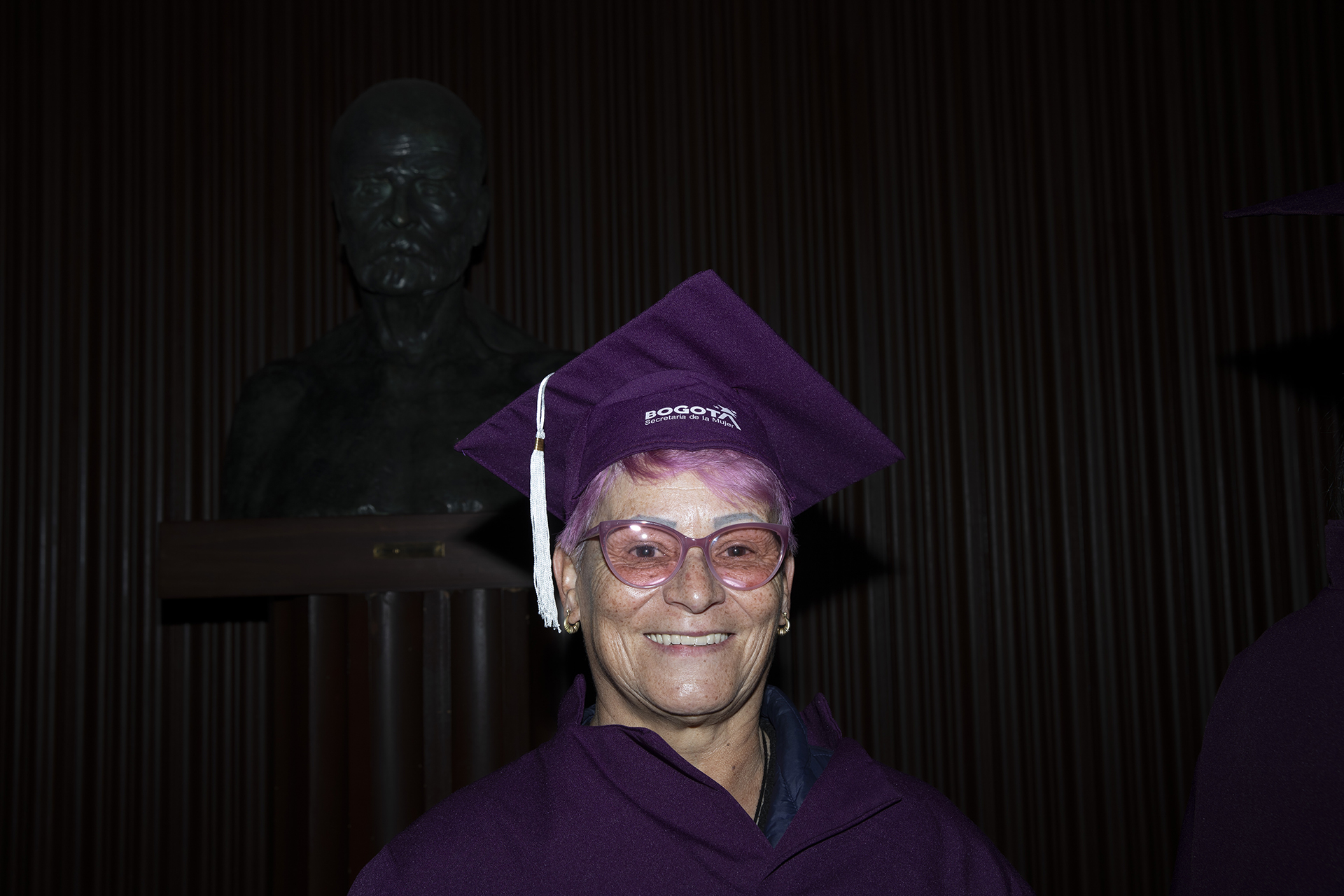

My trip overlapped with a citywide graduation ceremony for women who had completed month-long trainings in topics such as digital literacy, entrepreneurship, or professional caregiving.

The auditorium was packed with caregivers in purple graduation gowns and caps. Some had brought their children, who squirmed in seats or played quietly in the aisles. Others had wanted to come but couldn’t make it work, still home caring for someone who needed them.

One hundred and twenty-seven women were graduating that day. Many were over 65. For some, this was the first time they’d ever graduated from anything. The crowd sang along to the city’s anthem — “Bogotá! Bogotá! Bogotá!” — and women smiled proudly as they walked across the stage to receive their certificates.

The mayor and many of his high-ranking staff had come to congratulate the women. “You have to bet on their autonomy,” Laura Tami, the city’s Women’s Secretariat, said from the stage. Galán also laid out the administration’s strategy: freeing more women from violence, including economic violence, by giving them the tools to become more independent. It was a notably feminist message from a mayor who had run as a centrist technocrat.

The ceremony was moving, but it also raised real questions about scale. Over 3,500 women have completed these 30-day training programs, and the city hopes to increase that number to 9,000. This would be progress, but it’s a small fraction of Bogotá’s 1.2 million full-time caregivers.

Plus, my conversations at different care blocks surfaced the same challenge over and over. Many caregivers just didn’t know that these supports existed. And plenty who did didn’t trust them and didn’t believe Bogotá would actually keep them running, or that the services would actually be free. Some had shown up to care blocks looking for food and had been turned away empty-handed.

“We really do need to work harder on spreading the word [and] improving trust,” said Jason Díaz, the manager of the laundry services at the San Cristóbal care block. “There is a lot of stigma with government institutions.”

And sometimes the services are just not enough. Blanca Liliana Rodríguez told me about the at-home assistance program her family had benefited from last year. Rodríguez cares for her two adult sons — one with physical disabilities, one with mental disabilities — plus her 77-year-old mother and her 82-year-old father-in-law, who lives elsewhere. She’d been cooking three meals a day for her father-in-law and delivering them to his house.

The psychologists who came through as part of the government program worked with her family for three months, teaching Rodríguez and her sons how to communicate better, and even leading couples therapy with one of her sons and his girlfriend. They helped her realize she was taking on far more than she needed to. Her sons started helping with cleaning and picking up medications and she joined a new WhatsApp group with 30 other caregivers in her neighborhood that remains active to this day.

But when the time-limited services ended, Rodríguez was on her own again, still overwhelmed by the sheer scope of what she was managing. “Three months is definitely not enough time for the at-home assistance program,” she told me.

The city officials accompanying me on the visit immediately defended the short timeline. The program, they emphasized, was intentionally brief — designed to “install capacity” in caregivers and make them more resilient. It felt a bit like PR for a funding problem, not to mention condescending — these women were already extraordinarily resilient. They were just dealing with their own health and financial problems, their own exhaustion. Rodríguez said her memory had been getting worse.

At the beginning of this year, Bogotá stopped administering the at-home assistance program that had helped Rodríguez and her family. The Bloomberg funding that had supported the services had run out, and Galán’s team hadn’t figured out how to keep paying for it, let alone scale it up.

An independent evaluation, conducted over the last two years, found that the at-home program had freed up over 18,000 hours for caregivers and reduced their daily unpaid care work by more than an hour. Half of the caregivers reported feeling less burdened, and nearly half of people with disabilities became more independent.

But it was expensive. So the city tested a cheaper model, moving some therapeutic services into the care blocks rather than delivering everything at home. The new hybrid model cut costs per participant by 57 percent while still reducing caregiver depression and anxiety.

When I asked Galán’s administration whether the city would resume its at-home programming, Tami, the women’s secretary, responded that they planned to restart services next year. The city aims to run both models: full at-home assistance for caregivers who truly can’t leave their houses, and the lower-cost hybrid for others.

Meanwhile, Galán has continued expanding the less expensive parts of the care system. His team opened two new care blocks this year and added programming like nature therapy sessions run by the city’s botanical garden.

James Anderson, who leads the Government Innovation program at Bloomberg Philanthropies, told me that he expects the care block idea to expand further around the world, and that the United Nations Development Programme has been working actively behind the scenes to help. At a 2024 Bloomberg event in Mexico City last year, more than 70 mayors toured the city’s own version of care blocks, known as Utopías, and showed “incredible interest.”

Anderson thinks the model could follow the trajectory of climate action planning. Before 2005, he pointed out, mayors didn’t talk specifically about “climate”: they had water projects, sanitation projects, housing projects, all run by different agencies with no coordination. Twenty years later, every major city has a climate action plan that coordinates efforts across city hall. “That’s the trajectory that I imagine this issue will travel,” he said.

That vision is already underway. CHANGE, the City Hub and Network for Gender Equity, is a global network of city governments led by former mayoral staffers in London and Los Angeles. They’ve been working to spread the Bogotá model, developing an implementation guide and planning workshops for interested cities. Currently, they’re coordinating with a team in greater Manchester in England, have been helping Freetown in West Africa, and are actively involved in identifying a US city for a pilot next year, though conscious of the growing American backlash to anything associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“If you can’t make the case for why this won’t make your dollar stretch, there’s no point in having the conversation,” said Leslie Crosdale, CHANGE’s co-executive director. “It’s an efficient system and makes your city more resilient.”

Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, the mayor of Freetown, credits both CHANGE and Claudia López with helping kick off the idea in her city. Their care block is expected to launch by mid-2026, and in the meantime, Freetown is opening three temporary spaces before the end of December to meet demand from women in the community. “What excited me was being able to give back an opportunity that many women lost—the opportunity for education, the opportunity to just get health care,” Aki-Sawyerr told me.

Ai-jen Poo, who leads the National Domestic Workers Alliance, pointed to a disconnect in the US, where cultural expectations assume families can manage needs independently, despite millions being nowhere close to affording enough care. “You have this mismatch between the infrastructure and the reality where the individual family is just bearing the brunt in an impossible situation,” she said. “I think there’s a use case in the US for care blocks. It probably won’t look exactly the same, but I do think that there’s a lot there.”

Back in Bogotá, Jason Díaz, the 36-year-old manager of laundry services at the San Cristóbal care block, offered a glimpse of what that could look like in practice. He told me his job had made him more sensitive, more humane, teaching him to slow down more, and notice when someone needs help before they ask. “You learn to do it everywhere — at home, on the street,” he said. “It teaches you how to help people without expecting anything in return. The important thing is to be part of the solution.”

At the Castillo de las Artes care block, a sign hung on the wall in bright purple and green: “Cuidar no es ayudar, es corresponsabilidad.” To care is not to help; it is co-responsibility.

Spanish-English interpretation for reporting was conducted by Catalina Hernandez. This work was supported by a grant from the Bainum Family Foundation. Vox Media had full discretion over the content of this reporting.

The post What happens when a city takes women’s unpaid work seriously? appeared first on Vox.