Think of the French Riviera, and you think of opulence. Mega-rich blood-boy plasma parties in Saint-Tropez, F. Scott Fitzgerald farting around the Côte d’Azur clicking his fingers to jazz, that kind of thing. There is, however, another, far less glamorous side to the region—one that photographer Arnaud Dambry, born and raised in Cannes, has been navigating his whole life.

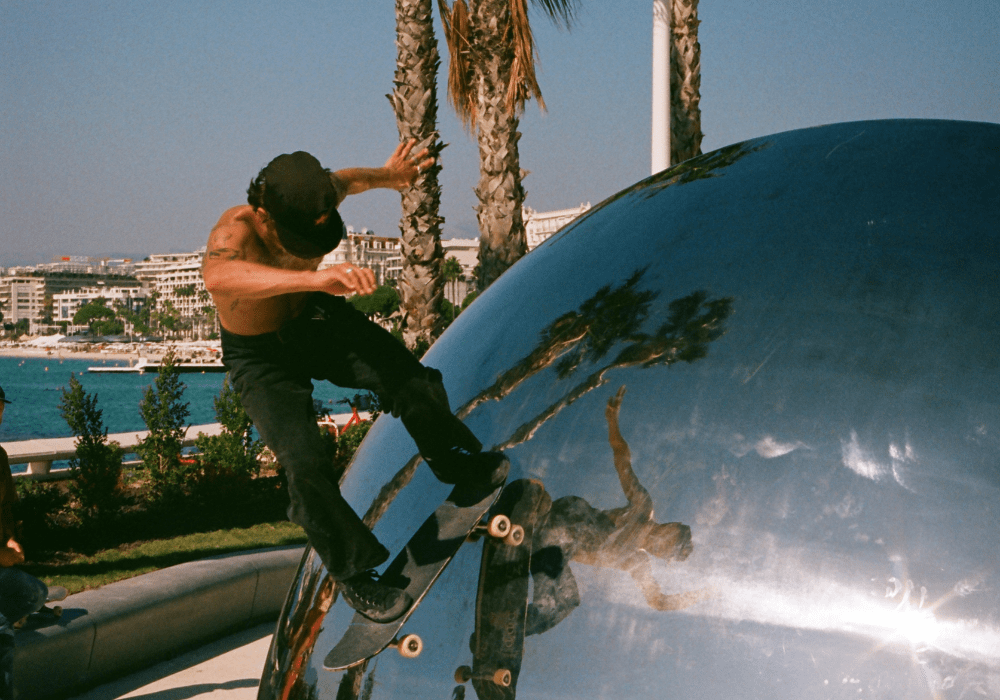

Here, he tells VICE about “the real French Riviera,” the skaters, ravers, graffiti kids, and outcasts who call it home, and why it isn’t just a playground for people who own leather driving gloves and asteroid-mining companies.

VICE: How did you get into photography?

Arnaud Dambry: When I was a teenager, I would take photos of my friends and the streets during skate sessions. At first I actually wanted to be a painter. I was a bit lost. I tried getting into art school and got rejected.

After that I moved to London and met this guy at Southbank who was shooting with little disposable Kodak cameras, way before the Instagram hype. I bought one too and instantly fell in love. For a long time, I became ‘the disposable camera guy.’ Not long after that the documentary LA Originals came out. It completely shook me. That’s when I told myself, OK, this is really what I want to do.

You only work with analog, right? Could you describe your process a little bit?

I completely fell in love with film photography for a thousand reasons. The color science, the fact that every film stock has its own personality (I still miss Fuji 400H), and the way you can’t just shoot non-stop like on a digital camera hoping one shot comes out good. I’m not gonna lie, I hate post-production. I can’t stand spending four hours editing a photo trying to give it a soul. Either the photo hits, or it doesn’t.

[My process] really depends on what I’m shooting. Most of the time I’m walking around with one or two cameras, watching, waiting for interactions or creating them. But when it comes to documenting a specific subject, I’ll do my research, and I always find a way to be at the right place at the right time.

What would you say are people’s main stereotypical ideas about the south of France?

I think there are two different lenses when it comes to the French Riviera: the international one and the French one. From the outside, places like Cannes, St. Tropez, and Monaco are all about luxury, parties, celebrities, and bling. For French people who don’t live there, it’s often seen as a retirement zone, where politics lean more toward older people and security rather than youth and culture. It’s the kind of place that’s great for a week of vacation, but you don’t really picture yourself living there. But when you dig a little deeper, there are other alternative realities trying to exist.

So what’s it actually like, in your view?

For me, the French Riviera is basically a bubble inside the country. It’s a region full of contrasts on every level. You can have some of the richest people in the world, the biggest yachts, the most luxurious palaces—then you turn your head and see people struggling to get by right in front of the sea, along with an invisible middle class that keeps everything running. It’s also contrasted because you’ve got two teams: the people who live by the coast and the people who live in the mountains; two completely different energies. When you grow up or live there, you don’t see the country’s social issues the same way as someone living in the northeast of France, for example.

In my reality, the Riviera is an incredible region where you have everything you could want. Some of the most beautiful beaches in the world, the mountains just an hour away, crazy nature, amazing food culture, and it’s sunny like 300 days a year. We have a strong, distinctive identity and culture. There’s a reason why people from all over the world save for a whole year, sometimes a whole lifetime, just to come here. When you think about it, that’s wild. For that reason alone, we should feel grateful for where we come from.

What drew you to documenting the counter-cultural side of it?

Mostly because it’s where I’m from. I’m part of the middle class you don’t really see when you come to the Riviera on vacation—the regular people who don’t have a €4 million villa with a pool in the hills, who don’t drive luxury cars, or any of the clichés people imagine when I say I’m from Cannes.

I’m just documenting my life and the lives of those around me, trying to shine a light on them. My friend circles have always been super mixed. I’ve hung out with people who have everything and others who have nothing. I’m lucky to have friends doing all kinds of things, some who throw the biggest underground parties in the area, some skaters who’ve been featured in Thrasher, others who are artists, graffiti writers, dancers, and so on. The Cannes Film Festival parties are funny to look at, but nothing beats being with your own people.

Has that counterculture always been there or is it relatively recent?

It’s always been there. Back in the 50s, there was a collective called Nouveau Réalisme, with major artists like Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Arman, Nikki de Saint Phalle, etc., who were doing kind of what we’re doing, just in a different era. Then in the 90s and early 2000s, a lot was happening with the rise of skateboarding and other subcultures.

After that, there was a gap. The next generations didn’t really keep those movements alive. A lot of people left to try their luck elsewhere, so the region was a bit neglected for a while. Then COVID indirectly shook things up. There’s definitely a clear before and after.

A lot has been happening over the past five or six years. Collectives are forming, new spots are popping up. It’s promising, for sure, and heading in the right direction.

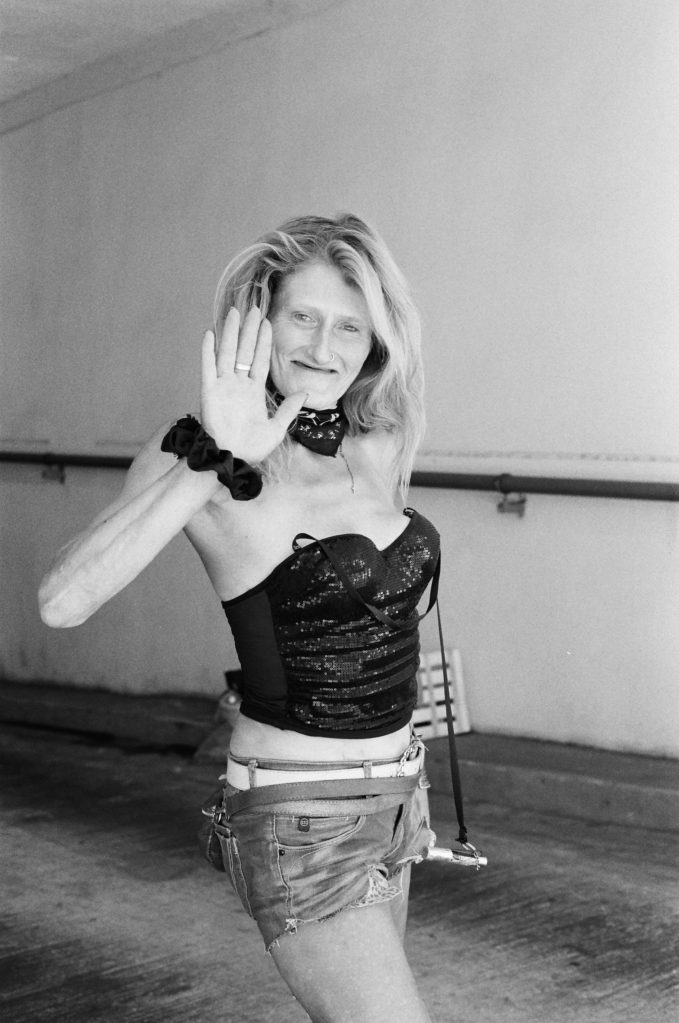

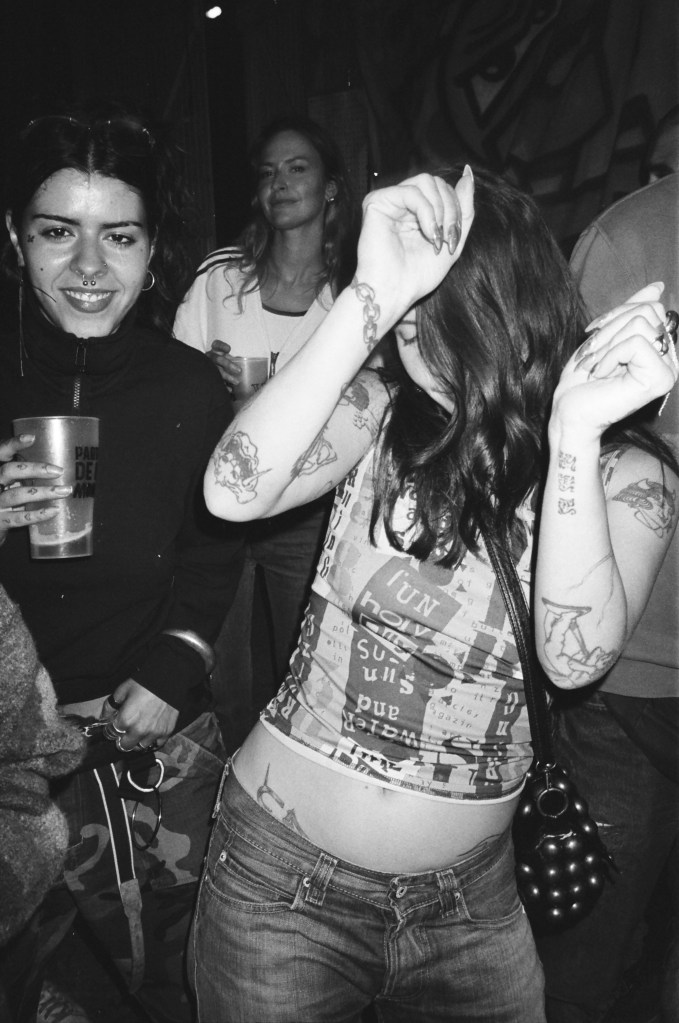

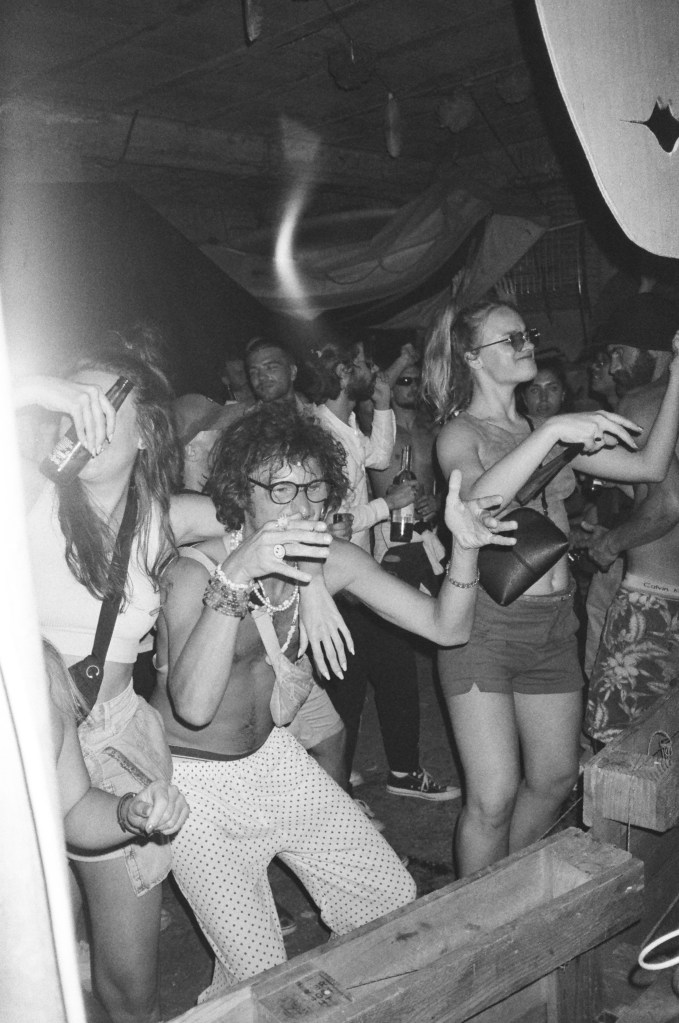

How would you describe the vibe of the French Riviera underground? What kind of music gets played at the parties? What does a typical Friday night look like?

Electronic music has definitely taken over a lot of the scene. You can find really niche parties with international DJ line-ups ( Romanian, UK, Italian) as well as groovier nights in clubs and other spots. There’s also been a lot of growth in hip-hop events lately, with local artists, DJs, and some big names from the French music scene.

Honestly, today you’ve got a bit of everything. Compared to a few years ago, the scene has changed a lot for the better. That said, underground culture means it takes time to put together cool, high-quality, safe events, so we’re not yet at the same pace as a capital city where you can go out anywhere every Friday night. But step by step, we’re getting there.

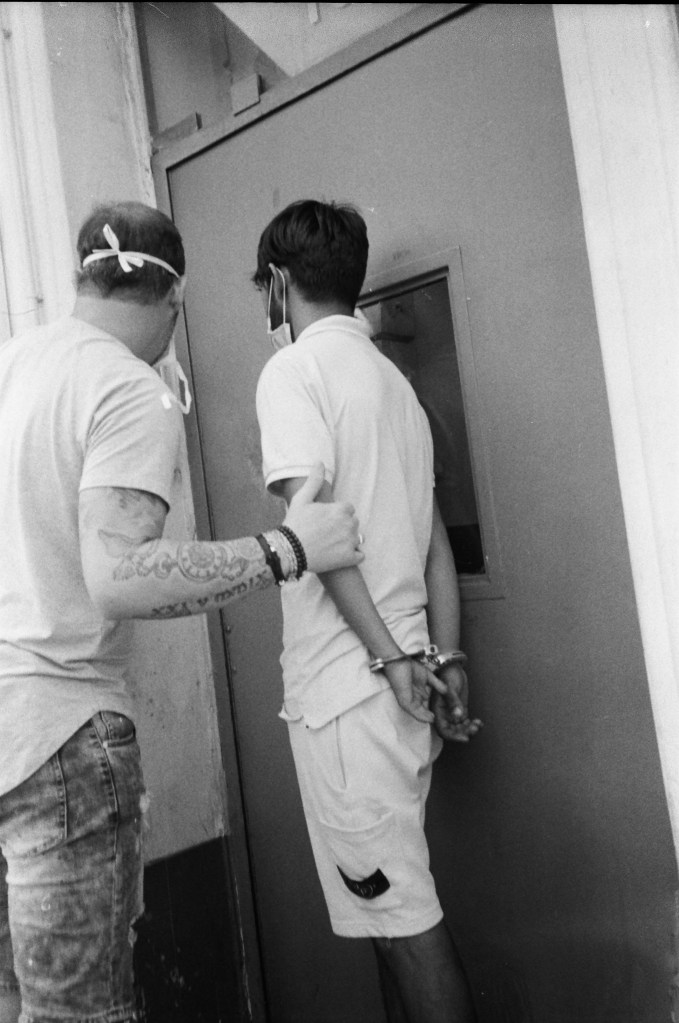

Is there an ethos that unites the people in your photographs?

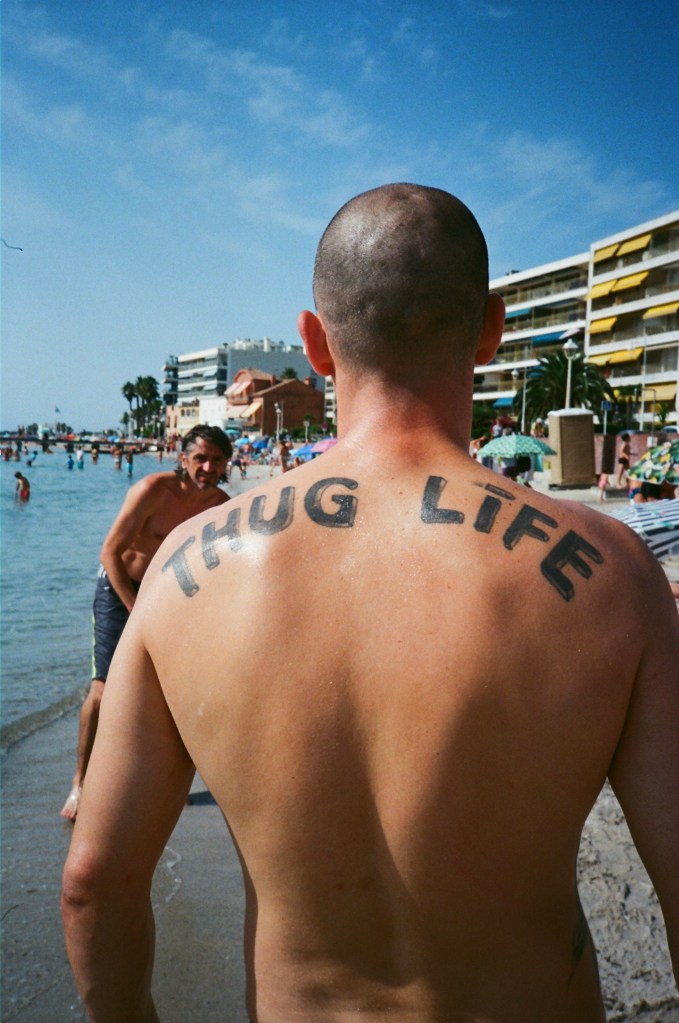

The people I photograph around the world are often individuals who are free or searching for freedom, and that’s exactly what draws me to them. A way of being, a spontaneity, a desire to break free from other people’s expectations. Deep down, their quest for freedom reflects my own. I have that same deep need to be free, and I think it’s because of that shared energy that people let me into their lives and trust me with their image.

Who’s the most interesting or memorable person you’ve photographed?

There are so many interesting people I’ve had the chance to photograph in the South, but I remember one guy in particular at the wild Decadance parties my friends used to throw. He was in a wheelchair, came to every party, and would dance front left until late at night, like his disability didn’t even exist. I’ve always had a lot of admiration for that guy.

You co-founded an art collective called Le Sud Fait Mieux, which means “The South Does It Better.” Tell me a bit about that.

That’s our way of saying thank you to the South. When you’re having a good time with your friends, the sunset is perfect, you’re roasting on a beach next to the turquoise water or whatever the vibe is, you just say: ‘le sud fait mieux.’ It basically became a little saying within our group.

It was born from a desire to bring some new energy back to the south of France after COVID. There was an open lane right after the first lockdown, and everyone had that fire to create cool projects after being stuck at home for so long. A lot of collectives popped up, most of them focused on partying, but we wanted to do something different. We’re all artists from different worlds—photographers, DJs, designers, rappers, painters, etc—and the idea was to create something people from the region could relate to, in one way or another.

The problem, like in a lot of countries, is that everything is centralized in the capital, and we all felt kind of overlooked. So, instead of waiting for things to come to us, we decided to make it happen ourselves. It’s been almost five years now, and I just want to thank my whole team: Tino, Fa, Gab, You, Pris, and Pierre.

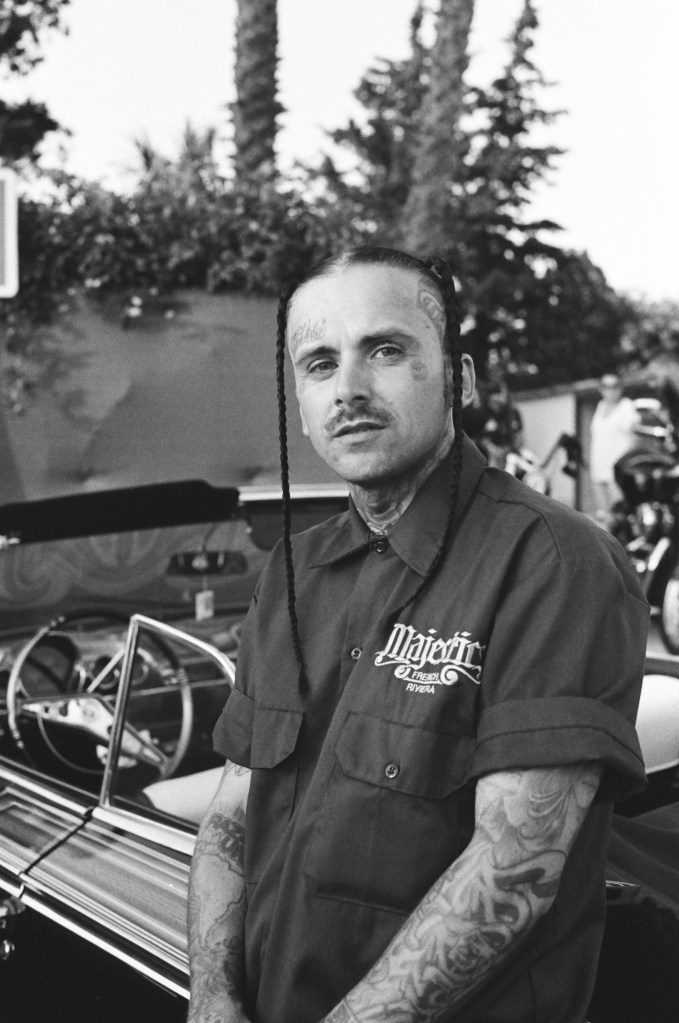

What’s the story behind these shots (above)?

This is my homie Duardo in the photo, a real one. A guy coming from the lowriding, tattoo, and Chicano culture. He’s exactly the kind of person who keeps the culture alive down here. He’s a top tattoo artist in our area, and with his crew, they set up a spot dedicated to tattoos and cars, kinda like what Cartoon and Estevan Oriol were doing in L.A. back in the 90s. These photos were taken at one of their lowrider meetings. He and his crew basically have one of the biggest car collections in France.

How would you describe the alternative French Riviera in three words?

I’d say it’s a “work in progress.” Come check us out, you won’t be disappointed. There are real people here!

The post Bad Boys of the French Riviera appeared first on VICE.