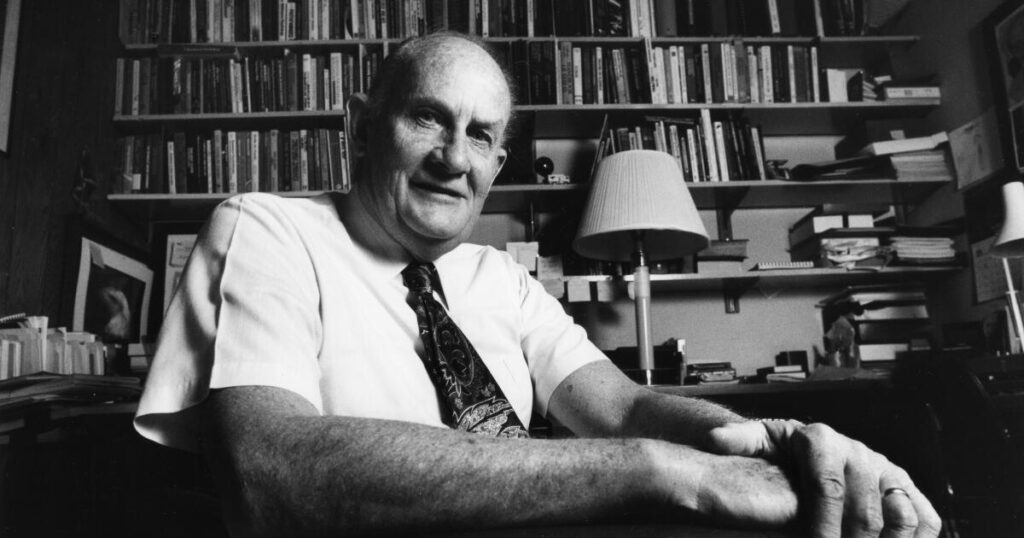

Robert Docter, an L.A. school board member in the 1970s who successfully pushed to end corporal punishment and who sacrificed his political career trying to integrate campuses through busing, has died at 97.

Docter also taught for 56 years at Cal State Northridge and served for decades as a regional leader within the Salvation Army.

He died at home in Northridge from what family members describe as neurological complications on Nov. 3.

“He always could see the possibility for students and their teachers and their families,” said Diane Watson, a former ally on the school board who went on to serve in the state Legislature and Congress. “You could follow him because you knew that he chose to do the right thing for the young people.”

As a school board member from 1969 to 1977, Docter was most closely identified with two issues — taking away the long-held right of school staff to hit children and trying to quickly and aggressively address the harms of segregation.

Docter had been a school board member for six years when he and allies, after multiple tries, pushed through a ban on corporal punishment — also referred to as spanking or paddling — by a 4-3 vote in 1975.

“It is child-beating and we should eliminate policies that permit child-beating,” Docter said. “Administrators and teachers should not be able to do what a Marine Corps drill sergeant is prohibited from doing.”

At the time, an estimated 7% of California districts had banned corporal punishment, although Gov. Jerry Brown had just signed a law requiring parental permission. Banning corporal punishment also had been a primary demand of student and teacher activists who took part in widespread Latino student walkouts from L.A. schools in 1968.

It took several years for the ban to take full effect as the school district developed other disciplinary methods.

The issue remains unsettled. In 2023, then-U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona wrote that “corporal punishment in school is either expressly allowed or not expressly prohibited in 23 states” and that “corporal punishment in schools is likely underreported.” Cardona called for its use to end.

Battle over forced busing

Docter’s efforts to promote comprehensive integration were to fail.

As the school board president, Docter became the face of the school system’s effort to carry out court-ordered, mandatory integration, including through forced busing, which he supported as a social-justice imperative.

“I believe in a multicultural, multi-ethnic society,” he said in a 1992 interview. “I was looking for sensible ways to achieve this.”

The dispute over busing divided the city, and was especially opposed in the San Fernando Valley, where Docter lived. Officers were sent to guard his home amid death threats.

“People were anxious, confused,” Docter said in 1992. “They were concerned about the lack of control: ‘I bought my house in this neighborhood so my child could go to this school!’ They were bitter. Many felt betrayed.”

There also was pressure from the other side — with liberal activists including future school board member Jackie Goldberg asserting that citywide integration should be the standard and could be mapped out to avoid bus rides longer than 20 to 30 minutes. She was concerned that Docter would weaken in his resolve, Goldberg recalled this week.

Docter remained firm.

In 1977, anti-busing parent activist Bobbi Fiedler ran against Docter, winning 56% of the vote.

“He was the epitome of the left-wing, social-planning liberal,” Fiedler said years later. “He was on the wrong side of the issue. He was out of touch.”

Docter said later that busing “should have been introduced on a voluntary basis to dispel fears among the majority population and resist white flight.”

Ultimately, the legal and political landscape shifted and L.A. Unified — with court approval — developed voluntary integration that focused substantially on magnet schools, which have special, desirable programs and prioritize admissions that promote integration.

Limited forced busing barely ever started — and was never truly carried out.

By then, however, thousands of white parents had moved out of the district or pulled kids from Los Angeles public schools, accelerating an evolution in demographics that already was in progress. White enrollment was 55% in 1963 — when the first school desegregation suit was filed — and 37% white in 1976 as the busing dispute peaked.

It stands at 10% today — a slight increase over recent years — and remains heavily concentrated in relatively few areas.

Integration through busing “didn’t fail,” Docter said later. “We just never tried it.”

Salvation Army connection

Robert L. Docter was born July 20, 1928 in San Francisco to Lloyd and Violet Doctor, who worked as Salvation Army pastors, and moved to L.A. in 1945 — and Docter graduated from Fairfax High the following year.

His connection to the Salvation Army was to be lifelong. He met his future wife, Dolores Diane Beecher, at a Salvation Army summer camp. They married in 1953.

He played in the Army band for more than 70 years, marching in its Tournament of Roses band more than 50 times. He led open-air services at the corner of Hollywood and Vine.

In 1983, he founded New Frontier Publications for the Salvation Army, serving as editor until 2017. In this role, he also wrote more than 600 columns. His writing became “a companion to thousands, offering wit, wisdom and spiritual honesty” the Salvation Army wrote in a tribute.

“He invited us to see the world through a lens of hope, sincerity and conscience,” wrote Christin Thieme, his successor as editor. “He believed deeply in the power of words, yes — but even more in the power of the character behind them.

in 1992, the organization admitted him to the Order of the Founder, the highest honor bestowed by the Salvation Army to a lay member.

A bond with local schools

After his parents took the family to L.A., Docter attended local public schools, graduating from Fairfax High.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in English from UCLA in 1952 and then in 1956 a master’s in education from USC, and a doctorate in educational psychology from the university in 1960.

He also served in the U.S. Army from 1952 to 1954, stationed at Fort Ord in Monterey, and played trumpet in the 6th Infantry Division Band. After that, he taught at Vanalden Elementary in Tarzana for six years while earning his advanced degrees.

In 1960 he Joined the education faculty of San Fernando Valley State College — which later became Cal State Northridge.

Dr. Docter — as he was widely known — was an associate professor of education and a father of children in the public schools in 1969, when he became one of 21 candidates for three board seats, saying that the state’s largest school system too often maintained an unsatisfactory status quo rather than updating its instructional methods.

On the board, he became an ardent L.A. Unified defender while also pushing for change. He called out fellow board member J.C. Chambers as “racist” when The Times quoted Chambers saying he did not want to “mix the races” and made other derogatory comments about Black students. Although Docter staunchly supported union bargaining rights, he had a falling-out with the teachers union that undermined his doomed reelection campaign. He lost the union endorsement after supporting a plan to integrate teachers as well as students — which would have resulted in some forced reassignments.

He wrote three books: “A View from the Corner” (2008), alluding to the name of his regular column, “Integrity: A Complete Life” (2015) and a novel, “Lost and Found in Montana” (2022).

Docter did not run for office after leaving the school board.

He “didn’t have political ambitions,” said daughter Sharon Docter. “He just cared about education. This was his passion. … What he wanted was to make a difference.”

He continued to ponder the state of schooling, expressing qualms about reducing education to numbers on standardized tests. Instead, he said in interviews, there should be more emphasis on ethics and morality as well as critical thinking and arts education.

He is survived by his twin brother, Richard F. Docter. His wife of 71 years died on April 27. Other survivors are six children — Sharon as well as Richard L. Docter, Janet Pollock, Mary Docter, John Docter and Julie Jennings — 15 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

A celebration of life will be held at the Salvation Army Pasadena Tabernacle Corps on Sunday, Dec. 7, at 2 p.m.

The post Robert Docter, L.A. schools leader who opposed spanking, fought for integration, dies at 97 appeared first on Los Angeles Times.