Ricardo Lara’s transition from influence-brokering state legislator to autonomous insurance regulator was rocky.

Almost immediately upon assuming office in 2019, the California insurance commissioner was discovered soliciting money from those he regulated, even allowing his campaign fundraiser to set his office calendar.

“I must hold myself to a higher standard,” Lara vowed in the aftermath. “I can and will do better.”

Six years later, he is under two new investigations for potential campaign finance and ethics violations, and accused by consumer advocates of cozying up to those he regulates.

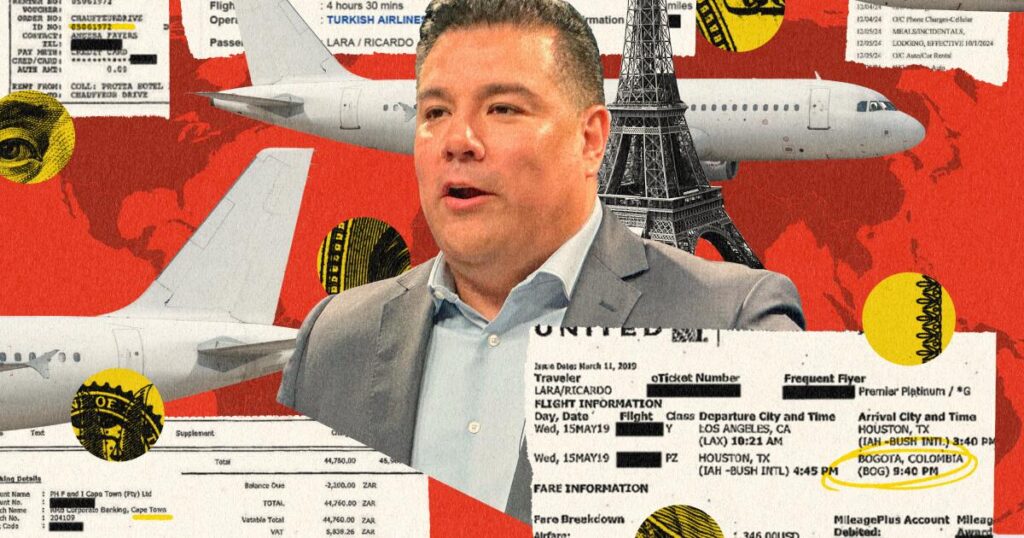

Lara has asked companies to make donations to favored charities, including those that have business before his agency, according to a Times investigation. The investigation found Lara logged at least 32 trips to 23 countries and territories — spending over 163 days abroad on state time — but consistently failed to disclose who paid for the five-star hotels, premium airline seats and fine dining.

California ethics laws mandate that elected officials like Lara disclose reimbursements for such travel to the state Ethics Commission and agency websites.

Lara says he followed all state ethics and campaign spending rules and acted in the best interest of sustaining a private insurance market.

Payment records for two-thirds of Lara’s trips are unreported or incomplete. The Times filed multiple public records requests for the full records, but the Department of Insurance at first said it didn’t have receipts for most of Lara’s spending.

In late November, however, the department released 452 pages of airline bookings for Lara made by the National Assn. of Insurance Commissioners, the powerful, industry-funded trade organization that creates model regulations for states to enact.

The nonprofit association paid for Lara’s first- and business-class travel expenses, including a $11,626 ticket to Singapore for a 2024 conference on Asian insurance issues. A $11,730 reservation to Nepal in January of this year was canceled after the L.A. fires. State employees accompanying Lara on foreign trips flew economy, for a fraction of the cost as their boss, state expense records show. Those include a state-paid $2,163 ticket to Tokyo in 2023 for a senior department official, while the NAIC put Lara in a $9,517 premium seat.

Insurance department staff said the NAIC covered many of Lara’s expenses. The association, which refused to disclose its spending on state regulators, is funded by fees on the insurance industry and state regulatory agencies, including $277,000 from the state of California.

Elected officials in California can accept free travel from nonprofit organizations for state business. However, California law requires that such gifts be disclosedquarterly to the Fair Political Practices Commission, be approved by the receiving agency, and are restricted to expenses the state would “reasonably” cover.

The insurance department for six years did not file reports for Lara. Lara’s press staff office said it neglected the filings because the prior insurance commissioner had also not reported travel sponsors, though The Times found former commissioner Dave Jones disclosed at least one such trip. Lara’s staff began submitting the mandatory disclosures in August after The Times raised questions. Those reports were incomplete.

The deputy commissioner who signed off on many of those incomplete ethics reports resigned in late November. The official said the departure is unrelated to the reports.

Transparency is a critical consumer protection when regulating California’s $96-billion insurance market, said Bob Fellmeth, a public interest lawyer and former prosecutor who was involved in writing California’s Proposition 103 insurance regulation law.

“ It’s disgraceful that he doesn’t keep track of his finances,” Fellmeth said.

Lara bristled at the suggestion he could be influenced by those who had him speak at foreign conferences, honored him at island receptions or supplied dinners at high-end restaurants.

“To simplify it as they’re ‘courting me’ or that I’m gonna be susceptible to something like that, it really diminishes me as an individual,” Lara said. “To assume that I’m gonna be, you know, beguiled by some reception, I think belittles my life’s work.”

Growing up in East L.A.

Lara, 51, the son of a farm laborer and a seamstress, proudly touts his working-class upbringing. His parents came to the United States as undocumented immigrants.

“Unlike …my predecessors, I actually come from these communities that have been disproportionately impacted by climate and climate change,” he said in an August interview with The Times.

Lara claims a long string of historical “firsts,” including being California’s first openly gay statewide public official, but it was his associations with some of L.A.’s most prominent Latino leaders and their labor union backers that accelerated his rise.

Lara, a San Diego State journalism graduate, started as communications director and then chief of staff for high-ranking lawmaker Marco Firebaugh, crafted media strategy for then-Assemblyman Kevin de León, and was district director for then-Assembly Speaker Fabian Núñez, whose own foreign travel and luxury spending drawn from campaign accounts prompted the Fair Political Practices Commission to adopt some of the state ethics rules Lara is now under investigation for potentially violating.

In a 2009 deal brokered by L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, Lara agreed to withdraw from his first statehouse race to clear the ballot for labor leader John Perez, who within a year was named speaker of the Assembly. When Lara won his own Assembly seat in 2010, Perez rewarded the freshman Democrat lawmaker with plum committee posts.

Lara was chairman of the powerful Senate budget committee in 2018 when, hitting term limits, he campaigned for and was elected insurance commissioner as a “counter-puncher” to Donald Trump.

As a lawmaker, Lara had focused on LGBTQ+ rights, advocacy for L.A.’s street vendors and the healthcare needs of undocumented children. Insurance policy wasn’t a strong suit, he acknowledged in a recent interview from the 17th floor of his Sacramento headquarters.

“I was learning the job and trying to understand what the department’s role was,” Lara said. “Nothing can prepare you for [going from] a legislator to a regulator.”

Lara said he stepped into office “leery” of the insurance industry and vowed to avoid “entrenched interests.”

Yet his social media posts show Lara spent the New Year’s Eve before his swearing-in at a party in London, accompanied by past and current lobbyistsfor Farmers Insurance. Lara said at the time that he considered his companions to be personal friends.

Almost immediately, Lara was embroiled in a pay-to-play scandal that involved his former boss.

The novice insurance commissioner was found to have taken campaign donationsfrom the insurance industry, including $54,000 from business associates and their family members seeking Lara’s approval on a license ownership transfer tied to the sale of workers’ compensation insurer Applied Underwriters, and for which Núñez and another consultant had been promised $1 million to secure the deal.

An insurance scandal

Office calendars showed Lara’s campaign fundraiser arranged and joined the insurance regulator’s business meetings. Those included state-paid travel to New York for “various climate meetings” during which Lara met with Núñez and others seeking his regulatory favor. Campaign donations followed the April 2019 trip.

“Effective public service demands constant adherence to the highest ethical standards,” Lara subsequently wrote in a September 2019 apology letter to three consumer groups. “I take full responsibility for that and am deeply sorry.”

The Times pieced together details of Lara’s foreign travels through campaign finance filings, partial state expense reports, expenses reported by fellow travelers, and the emails and expense records of insurance regulators from 10 other states that provided files California would not release.

The records show Lara has continued to schedule dinner receptions and meals with insurers he did not report as gifts.

He also asked those with business before his agency to help fund pet projects, including $145,000 for the Global Insurance Summit, a series of invitation-only climate risk gatherings where Lara was the host and principal speaker.

The Times identified more than half a dozen charitable donations on Lara’s behalf that came within weeks of meetings in his office, including a $10,000 donation in 2019 by a health insurer shortly after Lara approved its rate hike, for an event honoring Lara for his gay rights advocacy. It is legal for elected officials to solicit charity donations in their names, but the gifts must be reported along with a disclosure if the payor has a proceeding before the official’s agency.

Donors included power companies who met with Lara about state bailouts for utility-caused wildfires, and those lobbying Lara for expansion of the California FAIR Plan, the state’s property insurer of last resort. One contributor said Lara called him personally to ask for the donation, though state ethics filings named a department staff member as handling the gift.

Contributions made at Lara’s behest to organizations such as Ceres Inc. and Equality California included $25,000 from Uber, according to state ethics records. Four days after the donation was made, Lara flew from Burbank to San Francisco to meet with Uber executives. The subject of the March 2024 meeting was the $1-million uninsured motorists coverage the ride-hailing company was required to carry on its drivers.

In October, Uber secured passage of a law that dramatically reduces the insurance mandate to $60,000. Consumer advocates said the required coverage is so low that accident victims are at risk of unpaid medical bills.

Daniel Hinkle at the American Assn. for Justice, which represents trial attorneys, called the bill “a huge win for Uber to avoid accountability.”

Lara took no public position on the consumer impact of the insurance legislation.

Uber senior executive Ramona Prieto, with whom Lara met, did not respond to questions regarding the donation to Ceres, a nonprofit group that advocates for climate change policies.

Lawyers for the insurance department denied a public records request for communications related to the Uber meeting and solicitation of gifts for the insurance summit, saying no public documents existed.

An email from Lara’s office shows staff were instructed not to answer questions about the Uber contribution. His press office in a written response said such contributions “have no bearing on the Department’s impartiality or the Commissioner’s duties.”

Calendars and emails showed Lara also met frequently with insurance executives and their lobbyists about pending rate hikes, breaching an internal firewall meant to prevent undue industry influence. This was a departure from what former agency officials and an industry trade representative described as a long-standing practice against insurance commissioners discussing pending rate hikes with industry representatives.

The regulator’s calendar appointments even occasionally included notations on the size of the hike being sought. In one case, an insurer thanked agency staffafterward, saying that the department’s actuarial staff had sped up review of five pending filings after the company met with Lara.

Lara’s spokesman said there is “no such practice” prohibiting the commissioner from discussing pending hikes with insurers.

Missing receipts

A fraction of Lara’s travels were covered by the Department of Insurance, which by law is funded by fees collected from the insurance industry. Those include a 2019 trip to New York for World Pride festivities that included a Mets baseball game, spa visit, happy hour and VIP party, and in the same year, a trip to Bogota, Colombia, that included dinner with donors to an LGBTQ+ political candidate training foundation. The insurance department described these as “human rights” events.

Lara was afforded a security detail from the California Highway Patrol on some trips, which the insurance department paid for. His dignitary protection costs included $7,330 for a Florida-based firm to provide Lara a private car and driver in Bogota, and some $20,000 for two agents to cover Lara part of the time he was in South Africa. Lara’s staff said the regulator has no say in his security detail arrangements.

Two foundations provided $15,000 for Lara to visit England and Scotland. But the bulk came from trade organizations and Lara’s political donations.

Lara did not follow the accounting standards that applied to employees in his department. Agency emails show employees were required to submit detailed expense reports for their sponsored trips. On occasion, staff asked the NAIC to provide missing receipts.

Lara’s press office contended internal rules did not apply to the elected commissioner but acknowledged that Lara was required to disclose sponsored travel to state ethics officials.

Starting in 2022, Lara also began to tap nearly $250,000 in unspent campaign donations that had accumulated over the last decade. He moved the money into a placeholder account for Lara to run for lieutenant governor, an office for which he has expressed no interest but which would allow him to retain control of his amassed war chest after the deadline to close down his insurance commissioner campaign committee.

Elected officials are permitted to tap their campaign accounts for legitimate expenses related to running for or holding office. Those purely for personal benefit are prohibited.

Lara spent more than $107,000 on campaign credit cards to fly to, and dine and stay in, Washington, Seattle, Dubai, Dublin, New York, Costa Rica, Tokyo, Singapore, Switzerland, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand and Bermuda.

The campaign expenses included a $1,339 staff meal for three at a hotel in Dubai, a $5,000 department Christmas party in Long Beach, and numerous dinners for the commissioner and guests billed as campaign meetings, according to campaign filings.

One $125 “campaign meeting” at the Dal Raesteakhouse in Pico Rivera took place on the same day Lara posted on Facebook about a “birthday dinner” with a friend. The post showed Lara, in a black “Creature of the Night” shirt, and his companion sharing a Dal Rae booth under the tag “#gaybies.”

Following a report by the San Francisco Standard on Lara’s campaign-paid dining, and coverage by KGO-TV on his frequent travels, Lara is now the subject of twin investigations by the Fair Political Practices Commission.

The state’s ethics watchdog released records showing it is investigating whether Lara used campaign money for personal meals and entertainment. It also is looking into a complaint that he failed to report gifts he received while on his international trips.

He denies wrongdoing, contending the meals and receptions were not improper and were part of his public duties. His campaign treasurer would not comment.

Such investigations can be closed for insufficient evidence, or result in warning letters when public harm is low. In cases that merit action, the FPPC can prosecute and pursue fines of up to $5,000 per violation.

“Insurance is a global industry,” said Lara’s spokesman Michael Soller.

“To deliver results like these for Californians, you have to be in people’s faces — literally — to make the case for this great state.”

Soller would not provide details of whom Lara met with on these trips. Conference registrations show industry lobbyists typically made up at least half of the attendees at these gatherings. In some cases, his hosts had a direct interest in new regulations Lara was adopting.

Lara filed occasional disclosures for minimal gifts like popcorn and Lego sets. Soller said airplane tickets and hotel reservations, however, were not reportable “gifts” because they “facilitate public business.”

Event records obtained by The Times show the unreported invitations included luxury hotels, wine tastings, lawn parties, cruises, cocktail receptions and dinners — including those paid for by insurance companies. Agency staff did not respond to how those fit the definition of “public business.” State records do not show if Lara accepted all of these invitations, and CDI did not respond to a list of events provided by The Times.

The travel and entertainment that Lara failed to report included:

— A 2023 “Pride & Prosecco” lawn reception in Bermuda held by RenaissanceRe where Lara was a featured guest, followed by drinks, dinner and more drinks hosted by Conduit Re and a cocktail cruise the night after that.

— An insurance gathering in Argentina, which included a three-dinner evening with a traditional asado barbecue.

— A weeklong series of gatherings in South Africa in December 2024, where regulatory and industry groups held receptions on rooftops and in museums, wine tastings, and dinner meetings at fine restaurants and at two wineries. The insurance summit was capped off at the exclusive Mynhardt’s Kitchen Cathedral Cellar in South Africa’s Cape Winelands, an hour from Cape Town. The National Assn. of Insurance Commissioners booked Lara in the conference’s second-priciest luxury hotel, while Lara’s state security detail stayed 15 minutes away in cheaper accommodations.

The Cape Town meetings, held by the International Assn. of Insurance Supervisors, lasted five days. Lara, arriving from another conference in Ireland, stayed in South Africa for 11 days.

Lara’s staff said only two of those were personal days and Lara worked on state business the rest of the time. His office would not release Lara’s daily detailed itinerary.

Invoices show Lara’s California Highway Patrol team arrived six days before Lara and arranged a private car service, with driver, for three days. They submitted toll road receipts in the countryside for a day in which Lara’s staff contends he was working, and paid $88 for morning sightseeing in a big-game reserve.

“Safari ticket purchase to protect the ICwhile on Safari in S. Africa,” the agent wrote on his expense report.

The response from Lara’s office?

“The personal time of a public official is their personal time,” said Gabriel Sanchez, a spokesperson for Lara.

The post International travel. Fancy meals. Missing receipts. Who paid the tab for this top official? appeared first on Los Angeles Times.