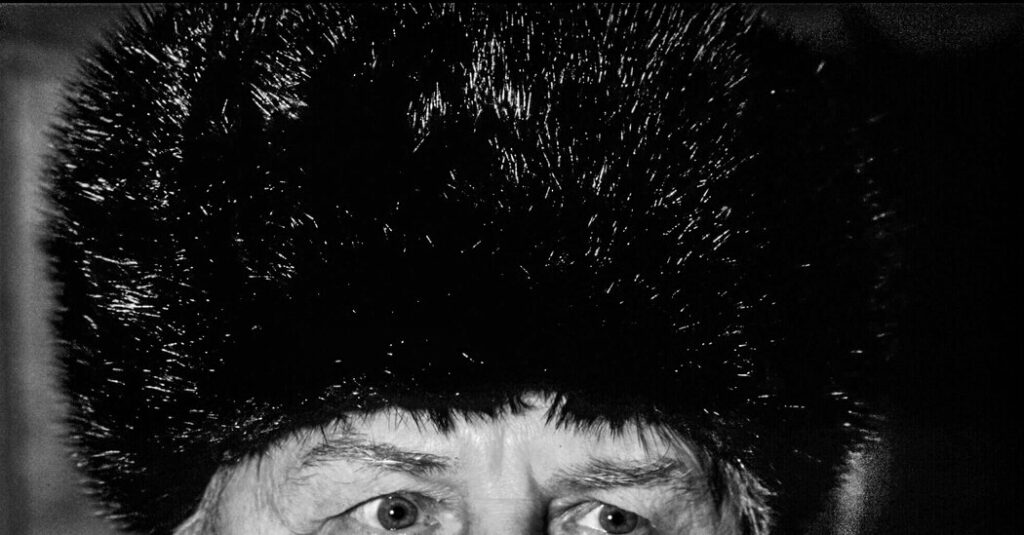

Yegor K. Ligachev, the Soviet Union’s second-ranking Communist Party official in the late 1980s, who first supported and then bitterly opposed the sweeping reforms of the top leader, Mikhail S. Gorbachev, that led to the nation’s historic political collapse in 1991, died on May 7, 2021, in Moscow. He was 100.

His death, announced at the time by local news media outlets, was not widely reported outside Russia. The New York Times learned of it while reviewing an obituary about Mr. Ligachev that was prepared in advance.

In the Soviet Union’s final years, as the world watched in amazement and decades of dictatorship and repression gave way to liberalizations under Mr. Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness), Kremlin watchers came to regard Mr. Ligachev as an enigma, symbolic of Russia itself, teetering between a past of untold suffering and a future of unknown perils.

A Siberian who said he lost relatives in Stalin’s purges and witnessed atrocities in forced labor in camps and collectives — and who was later accused of covering up mass executions as a Communist boss in Siberia — Mr. Ligachev remained a party stalwart for 40 years as he rose though its ranks. When Mr. Gorbachev was named general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in 1985, Mr. Ligachev became his top deputy — effectively the Soviet Union’s No. 2 official.

A member of the ruling Politburo for five years, Mr. Ligachev was responsible for party ideology and patronage. Many historians called him conservative but not reactionary — a blunt-spoken, white-haired enforcer with old-fashioned Bolshevik values who initially embraced the Gorbachev reforms to modernize and cleanse an insular and corrupt Communist rule.

When “Inside Gorbachev’s Kremlin: The Memoirs of Yegor Ligachev” was published in 1993, Serge Schmemann, then the Moscow bureau chief of The New York Times, wrote of Mr. Ligachev in The Times Book Review: “He saw the limitations of centralized economic control, the dangers of stifling discourse, the destructiveness of corruption. But the democracy he sought was ‘socialist democracy’ and ‘socialist pluralism.’”

As Mr. Gorbachev’s reforms proliferated under intensifying economic and political pressures, Mr. Schmemann wrote in that same review, “Mr. Ligachev very quickly reached the limit of what he was prepared to change. Private property, open criticism of Soviet history, political pluralism were all anathema to him, and by 1988 he had changed from comrade in arms to chief critic.”

Mr. Ligachev opposed electing party leaders by secret ballots and imposing mandatory rules for their retirement, and he fought heavy cuts in funding to the military and to satellite states. He also resisted lowering the Kremlin’s guard against freedoms of expression, artistic liberties and efforts to re-examine Soviet history. He insisted that cultural institutions should serve party interests. Above all, he opposed democratization of the Soviet Union.

Some analysts said Mr. Gorbachev retained Mr. Ligachev on the right as a counterweight to Boris N. Yeltsin, a critic on the left whose strident demands for accelerated reforms preceded his own ouster as head of the Moscow Communist Party in 1987 (each province or major city had its own party organization) and later from the Politburo.

Mr. Ligachev’s turn came next. After three years of escalating criticisms of the Gorbachev reforms, he was removed as the party’s ideological and patronage chief and assigned to agriculture. It was a humiliating demotion. Maneuvering behind the scenes, he survived in the Politburo for two more years.

His opposition to reforms almost seemed vindicated as Soviet economic stagnation deepened, unrest widened in non-Russian republics and Communist regimes in Eastern Europe began to topple. In 1989, Mr. Ligachev was elected to the Soviet Parliament in the first free elections of modern times.

At a historic party congress in 1990, Mr. Gorbachev and his ultimate reform — to end Soviet Communism’s monopoly on power — prevailed against his opponents’ final challenge. Mr. Gorbachev was re-elected party leader, and Mr. Ligachev, after losing his bid for a powerful new party post, was ousted from the Politburo. He soon announced his retirement. It was temporary.

After the Soviet collapse a year later, Mr. Gorbachev, having survived an abortive coup, resigned, and Mr. Yeltsin became leader of the new Russian Federation. Mr. Ligachev made a comeback in that fragile democracy. He was elected to the Communist Party’s Central Committee when it was re-formed in 1993 and elected three times to Russia’s Parliament. He was its oldest member when he lost his seat in 2003.

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachev was born in Dubinkino, near Novosibirsk in southern Siberia, on Nov. 29, 1920, three years after the Russian Revolution. Little is known of his family or early life. (In a 1990 profile, The Los Angeles Times said he came from “a peasant family.”) He was a young child in the last years of Vladimir Lenin’s rule and came of age during Joseph Stalin’s murderous purges of hundreds of thousands of people during the 1930s and ’40s.

“I was hardened by the years 1937 and 1949, when our family was subjected to unjustifiable repressions, when I was losing my relatives,” Mr. Ligachev told The Washington Post in 1989. “All this surely leaves one scarred, but strengthened politically.”

From 1938 to 1943, he attended the Moscow Aviation Institute, earning an engineering degree. He then returned to Novosibirsk, joined the Communist Party in 1944 while working at a war plant, and began his slow, steady rise to power.

For most of his career, Mr. Ligachev remained in Siberia, first as a leader of the Komsomol, the party’s youth division, and then, for 18 years — from 1965 to 1983 — as first secretary of Tomsk, an industrial and transportation hub. He was elected a nonvoting member of the Soviet Communist Party’s Central Committee in 1966 and a full member in 1976.

Mr. Ligachev and his wife, Zinaida, a teacher, had a son, Alexander, who became a university professor. Information about survivors was not available.

During his years in Tomsk, the province became self-sufficient in food production and developed oil and gas resources. Yuri V. Andropov, who became Soviet leader in 1982, brought Mr. Ligachev to Moscow in 1983 and assigned him to root out corrupt, incompetent party leaders. After Mr. Andropov died in 1984, Mr. Ligachev became Mr. Gorbachev’s protégé and, a year later, the nation’s second-highest official.

Analysts marveled at his swift rise from apparent obscurity in Siberia to power in Moscow. Some called him a deft political survivor who had impressed superiors with grit and loyalty. Others called him an ambitious manipulator who had outmaneuvered rivals and hoped to succeed even Mr. Gorbachev.

A few offered a more sinister interpretation. Several years after Mr. Ligachev’s expulsion from the Politburo, historians investigating mass executions in Stalin’s purges linked Mr. Ligachev to what they called a cover-up of the discovery of 1,000 bodies of people slain by the K.G.B., the secret police, in the Tomsk district, where Mr. Ligachev had been the party boss.

A 1993 article by Adam Hochschild in The New York Times Magazine said the bodies were found mummified in 1979 in the Siberian town of Kolpashevo. The article said the K.G.B. had fenced off the site and worked around the clock for two weeks to destroy all traces of the atrocities.

“The provincial Communist Party chief who presided over that 1979 cover-up went on to become one of the country’s most powerful men,” Mr. Hochschild wrote. “He was Yegor Ligachev, who soon became a member of the Politburo, a major conservative rival to Mikhail Gorbachev and — some Russians charge — a quiet participant in planning the failed coup of 1991.”

In her 1996 book, “Remembering Stalin’s Victims: Popular Memory and the End of the USSR,” Kathleen E. Smith, a Georgetown University political scientist, said that a Russia-based humanitarian group, the Memorial Society, had pressed the Kremlin to prosecute party officials, including Mr. Ligachev, for the cover-up. The Soviet courts, she wrote, refused to hear the case.

Robert D. McFadden was a Times reporter for 63 years. In the last decade before his retirement in 2024 he wrote advance obituaries, which are prepared for notable people so they can be published quickly upon their deaths.

The post Yegor Ligachev, Gorbachev’s No. 2 Who Turned Foe, Is Dead at 100 appeared first on New York Times.