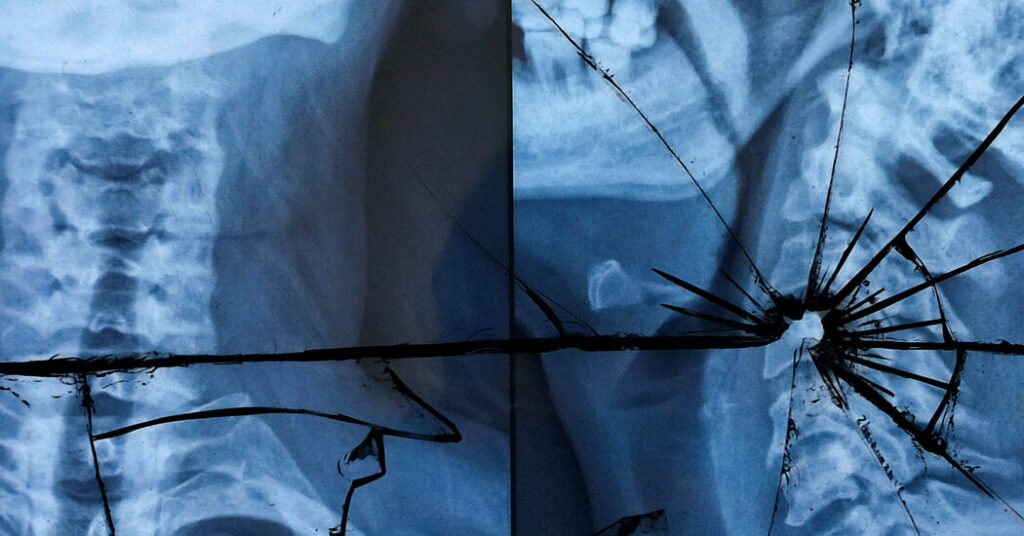

I recently got called to see a teenager ejected in a rollover car crash. The trauma team rushed him into surgery to stop major abdominal bleeding, but we all knew. When that much energy enters a skull, no operation can turn it back. He was declared brain dead. His death was a reminder of the staggering amount of suffering and loss of human life we accept from car accidents every single day.

Self-driving car company Waymo recently released data covering nearly 100 million driverless miles in four American cities through June 2025, the biggest trove of information released so far about safety. I spent weeks analyzing the data. The results were impressive. When compared to human drivers on the same roads, Waymo’s self-driving cars were involved in 91 percent fewer serious-injury-or-worse crashes and 80 percent fewer crashes causing any injury. It showed a 96 percent lower rate of injury-causing crashes at intersections, which are some of the deadliest I encounter in the trauma bay.

So far, other autonomous vehicle companies don’t report or report incomplete data. Waymo, by contrast, published everything I needed to analyze the data: crash statistics with miles driven that allow accurate comparison to human drivers in the same locations.

If Waymo’s results are indicative of the broader future of autonomous vehicles, we may be on the path to eliminating traffic deaths as a leading cause of mortality in the United States. While many see this as a tech story, I view it as a public health breakthrough.

The reasons autonomous vehicles are safer are straightforward. A system that follows rules, avoids distraction, sees in all directions and prevents high-speed conflicts will avert deadly collisions much more often.

These vehicles aren’t perfect. A passenger heading to the airport was recently stuck inside a Waymo that looped a parking lot roundabout for five minutes. Waymo issued a recall last year to update the software on its vehicles after one hit a utility pole at low speed while pulling over.

And there have been two fatalities and one serious injury in crashes involving a Waymo vehicle. In all three cases, however, human-driven vehicles caused the collision: a high-speed crash that pushed another car into a stopped Waymo, a red-light runner hitting a Waymo and other vehicles before striking and injuring a pedestrian, and a Waymo rear-ended by a motorcyclist, who was then fatally struck by a hit-and-run driver.

This last instance may give some skeptical readers pause. There’s a common misconception that these cars brake erratically and get rear-ended. But they are involved in far fewer rear-end injury crashes than human drivers are. And Waymo has never rear-ended another vehicle at injury level. Autonomous vehicle companies have to report every contact resulting in injury or property damage over $1,000, while studies show that humans don’t report the majority of accidents, even many with injuries.

In medical research, there’s a practice of ending a study early when the results are too striking to ignore. We stop when there is unexpected harm. We also stop for overwhelming benefit, when a treatment is working so well that it would be unethical to continue giving anyone a placebo. When an intervention works this clearly, you change what you do.

There’s a public health imperative to quickly expand the adoption of autonomous vehicles. More than 39,000 Americans died in motor vehicle crashes last year, more than homicide, plane crashes and natural disasters combined. Crashes are the No. 2 cause of death for children and young adults. But death is only part of the story. These crashes are also the leading cause of spinal cord injury. We surgeons see the aftermath of the 10,000 crash victims that come to emergency rooms every day. The combined economic and quality-of-life toll exceeds $1 trillion annually, more than the entire U.S. military or Medicare budget.

This is not a call to replace every vehicle tomorrow. For one thing, self-driving technology is still expensive. Each car’s equipment costs $100,000 beyond the base price, and Waymo doesn’t yet sell cars for personal use. Even once that changes, many Americans love driving; some will resist any change that seems to alter that freedom.

Not all autonomous vehicles are created equal. Many of the devastating crashes that capture headlines involve “driver assistance” systems — the kind found in millions of Teslas and other modern cars — where humans need to remain vigilant behind the wheel. Tesla recently released results suggesting that what it calls “full self-driving (supervised)” decreases the frequency of crashes, but we will still need more independent analysis of that data before we can draw firm conclusions. And research on other partial automation vehicles have yielded mixed results. A study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety found “no convincing evidence” that partial automation reduces crash rates.

Waymo operates cars with no human driver. Their vehicles use cameras, radar and specialized sensors, known as LiDAR, that create detailed 3-D maps. They operate only in cities where they’ve studied every intersection.

We don’t yet know if other autonomous vehicles will have a similar safety record. Tesla recently launched a driverless pilot program (with a person supervising from the frontpassenger seat) in Austin, Texas, but has not released performance data yet. Other companies operate fully self-driving ride-hail services, but so far without comparable data transparency.

There is likely to be some initial public trepidation. We do not need everyone to use self-driving cars to realize profound safety gains, however. If 30 percent of cars were fully automated, it might prevent 40 percent of crashes, as autonomous vehicles both avoid causing crashes and respond better when human drivers err. Insurance markets will accelerate this transition, as premiums start to favor autonomous vehicles.

Researchers predict that the shift to autonomous vehicles will take more than a decade. We should use that time to plan wisely. Autonomous vehicles improve safety remarkably when they replace humans driving personal vehicles, but if they end up primarily pulling riders from trains and buses, which are already exceedingly safe, there will be far less of a benefit. It makes sense to deploy these vehicles through commercial robotaxis, which is the current approach, but we need deliberate work force planning to address the way that this will threaten the livelihoods of America’s millions of commercial drivers.

Rather than grapple with these challenges, many cities are erecting roadblocks. In Washington, D.C., local politicians have long postponed a key report that would facilitate the broader use of these vehicles despite 18 months of successful vehicle testing. In Boston, the City Council is considering mandating a “human safety operator” in every vehicle, effectively stalling meaningful deployment. Policymakers need to stop fighting this transformation and start planning for it.

Federal leadership is essential. Current regulations require companies to report crashes, but not miles driven or where those miles occurred. We need the denominator, not just the numerator. Data reporting requirements should include crash rates, miles driven and where, and safety performance. Independent auditors should verify this data against police reports, insurance claims and privacy-protected medical records.

This transformation will happen. We can guide it toward a safer, more equitable future or let it unfold haphazardly around us. There’s a future where manual driving becomes uncommon, perhaps even quaint, like riding horses is today. It’s a future where we no longer accept thousands of deaths and tens of thousands of broken spines as the price of mobility. It’s time to stop treating this like a tech moonshot and start treating it like a public health intervention.

Dr. Jonathan Slotkin is an executive and vice chair of neurosurgery at Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania. He is co-founder and general partner of Scrub Capital, a venture firm that invests in health care start-ups.

Graphics by Bhabna Banerjee. Source images by Valeriy Volkonskiy and Salah Uddin/Getty Images.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Don’t Fear Self-Driving Cars. They Save Lives. appeared first on New York Times.